The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) says migratory wild birds are spreading avian influenza around the globe. The Parma, Italy-based food safety agency figures migration routes crossing the north-eastern and eastern EU borders are the most likely pathway for avian flu entering the continent.

In the United States, experts at the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service say the spread of highly pathogenic avian flu viruses involves both wild and domestic birds.

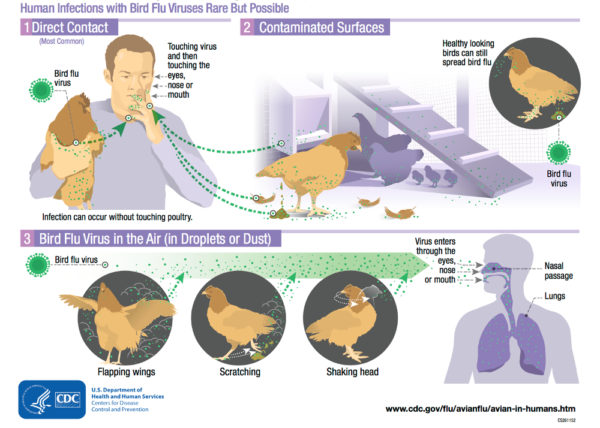

In rare instances, people become infected, usually by touching surfaces contaminated with bird saliva or feces and then touching their own mouths and noses, or preparing or eating food without washing their hands after being around birds. People can also inhale the virus from contaminated droplets and dust in the air, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Unlike in humans, the virus poses a huge threat to commercial and backyard bird flocks.

Two years ago avian flu subtype H5N2 burned through commercial poultry and backyard flocks in the United States, requiring the destruction of 49 million domestic birds for losses of $1 billon.

Europe and Asia were also hit with the avian flu outbreaks.

The EFSA’s experts have since assessed the risk of avian influenza entering the EU and reviewed surveillance approaches – which include monitoring by Member States and the actions they take to minimize its spread. Their scientific advice is based on a thorough review of all the information on the avian influenza outbreaks that have occurred in recent years.

“This work will enhance the EU’s preparedness for avian influenza outbreaks, just ahead of the peak influenza season in autumn and winter. It would not have been possible without the close cooperation with Member States affected by this epidemic,” said Arjan Stegeman, Chair of EFSA’s working group on avian influenza.

One of the main recommendations is that the public should let local veterinary authorities know when and where they find dead water birds – particularly during the influenza season.

Testing farmed water birds – such as ducks and geese – for avian influenza is also important because they can easily come into contact with wild birds, which can then spread the virus. The report recommends blood analysis for live poultry and testing of water birds found dead.

Testing farmed water birds – such as ducks and geese – for avian influenza is also important because they can easily come into contact with wild birds, which can then spread the virus. The report recommends blood analysis for live poultry and testing of water birds found dead.

Farmers and poultry keepers should adopt appropriate management measures to increase biosecurity. These include preventing direct contact between wild water birds and poultry by using nets or keeping poultry indoors during peak influenza season, and avoiding the movement of animals between farms.

Live poultry and backyard flocks should not be allowed access to water sources that are available to wild birds.

International cooperation

EFSA, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), the EU reference laboratory on avian influenza and authorities in affected Member States have also published a report on the avian influenza situation in the EU and at global level. The report will be updated quarterly.

The United States has not seen a repeat of the H5N2 Eurasian Avian Flu since the 2014-15 outbreak. In 2016, the Mississippi flyway was connected to the infection of 43,000 birds in Indiana, and earlier this year there was an HPAI outbreak in Lincoln County, TN.

“Avian influenza is caused by influenza Type A virus (influenza A), Avian-origin influenza viruses are broadly categorized based on a combination of two groups of proteins on the surface of the influenza A virus: hemagglutinin or ‘H’ proteins, of which there are 16 (H1-H16), and neuraminidase or “N” proteins, of which there are 9 (N1-N9),” according to APHIS.

“Many different combinations of “H” and “N” proteins are possible. Each combination is considered a different subtype, and related viruses within a subtype may be referred to as a lineage. Avian influenza viruses are classified as either ‘low pathogenic’ or ‘highly pathogenic’ based on their genetic features and the severity of the disease they cause in poultry. Most viruses are of low pathogenicity, meaning that they causes no signs or only minor clinical signs of infection in poultry.”

(To sign up for a free subscription to Food Safety News, click here.)