Dallmier, president of Clarkson Grain Co. of Illinois, shared his thoughts on what millennials will be demanding from farmers in the future during the Farm Progress Virtual Experience. He noted from the 1940s to the 1980s, family investments centered around the price of calories. But with the rise of the middle class over the past 20 years, there is enough income to afford calories. He says the past five years saw a gravitation toward buying based on an individual’s value system.

“Millennials and shoppers in general are much more interested in how their food is produced, and that extends to the farm in transparency, in personalization and convenience, all the way to the seed to the grower and through the entire supply chain,” Dallmier said. “One thing that is clear is that convenience, personalization and transparency will drive this market.”

The question the agriculture industry needs to answer is how it meets that new demand, he added, and how farmers think about what they do in a different context.

Change in shopper mentality

One global company that looks at data and provides insight on consumer and market trends worldwide is The Nielsen Co. It has been tracking and analyzing changes in the marketplace for the past 90 years.

According to a 2019 Nielsen study, consumers are buying products that matter most to them. Rising to the top of its list are locally grown or sourced, no added sugar, free from GMO and antibiotic free.

“In 2018, over 80% of U.S. households had at least one USDA organic product in the cupboard,” Dallmier said. “And it has grown into an over $50 billion industry with year-over-year growth and is the envy of the industry.”

Dallmier said that protein and produce are driving non-GMO and organic demand. “Non-GMO egg sales are increasing its share of the protein sector,” he explained. Another segment continuing to increase is organic chicken, whose demand rose 4% year over year in 2018 to 2019.

Consumers are willing to pay a premium for these types of products.

Another Nielsen study on premiums consumers will pay for products found 41% willing to spend more for products that contain organic or all natural ingredients, 38% for environmentally friendly or sustainable materials, and 30% for those that deliver social responsibility claims.

Where’s the farmer value?

Dallmier noted that it will take a change in mindset and production practices to meet demands, but it will ultimately increase profits for farmers.

“There are 186 really good reasons per acre to look and listen to what your customers are requesting and what demand is saying,” he said.

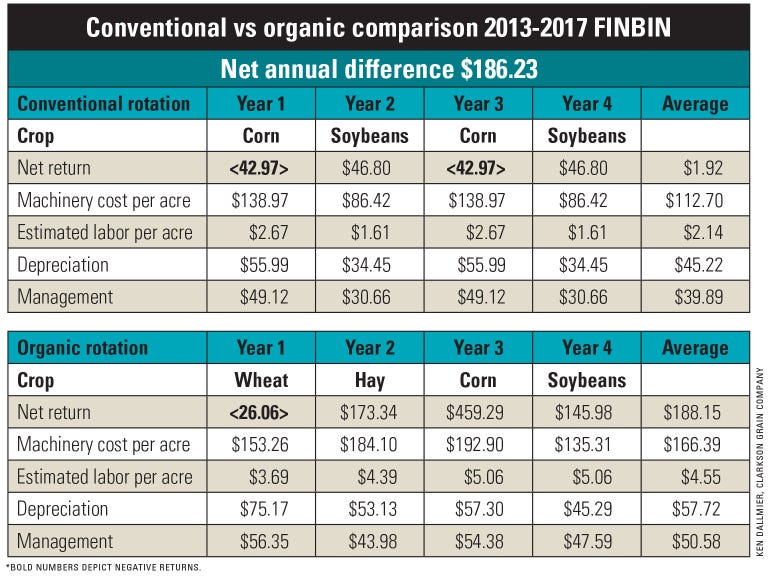

While the 2019 data is not yet available, a comparison published in 2018 by the Flanagan State Bank in Illinois, which used data provided by FINBIN from across the Midwest, showed a net annual difference of $186 per acre when raising organic versus conventional crops over four years. This includes a rotation of organic wheat, hay, corn and soybeans.

“We have growers that net more than their conventional commodity neighbors gross,” Dallmier said. For 2020 and 2021, he sees premium for organic and non-GMO holding steady. He said a general premium rule of thumb is raising organic corn and soybeans will bring two and a half to three times above the commodity cash price.

When it comes to non-GMO corn and soybeans, it is about 10 cents to 70 cents per bushel above cash price. Non-GMO premiums can be further boosted by growing identity specific varieties for food or specialty feed uses for companies. “The growers that serve these markets will gain that market distinction, and market distinction brings a premium," Dallmier said.

Farming for the family

A switch in farming practices may not be just about meeting consumer demand, although Dallmier said it is an important aspect. He said these new demands may have family farms rethinking what it means to be “successful.”

“The principle challenge, to me, is changing the mindset from thriving on 300 to 500 acres, rather than just surviving on 3,000 to 5,000,” he said. “We all grew up thinking we were outstanding farmers, and we were successful because I produce 80-bushel beans. Now we need to think about I'm successful because I net $200 an acre.”

Dallmier said reducing costs over bushels is not sustainable in the long term. He noted farmers need to identify new world markets and new domestic demand that adds value to the supply chain.

For more on new crop markets such as organic, visit FPVExp.com.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like