In 2020, the Paris-based research organization Future Earth released a report on climate change that combined the insights of more than 200 leading scientists from more than 50 countries.

They concluded that the challenges confronting humanity – extreme weather events, the decline of life-sustaining ecosystems, food insecurity, and dwindling stores of fresh water – compound one another. On their own, they’re devastating enough, but taken together they may wind up destroying our cities, our countries, our planet, and ultimately us.

But does it need to be this way?

The 10 graphs featured in this article – in the fields of economic progress, health, social services, and technology – show that, perhaps for the first time in history, human beings can exert significant control over what happens to our species and our planet, and that our future is better than most of us think.

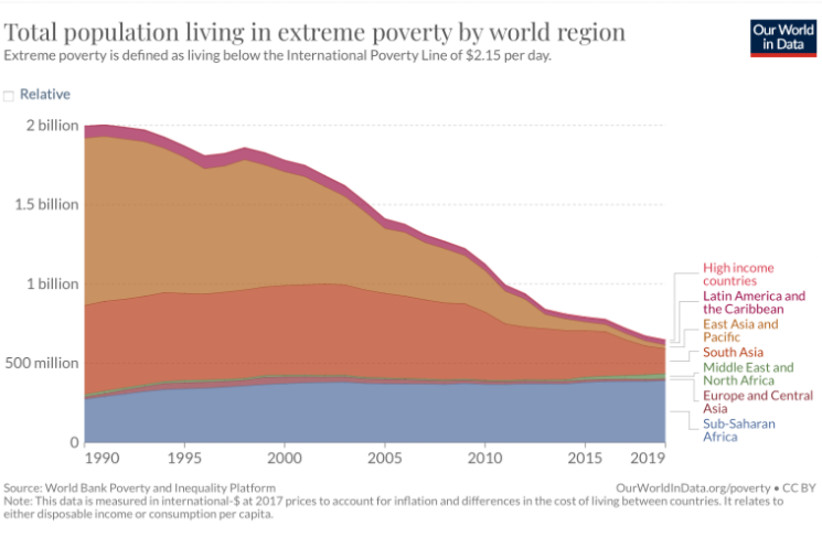

1. Extreme poverty is declining

The last three decades have seen a huge decline in the number of people living on $1.90 a day. In 1990, two billion of the 5.28 billion people in the world, or nearly 38%, were below the extreme poverty line. By 2019, that number had shrunk to 648 million out of 7.68 billion, approximately 8.4% of the world’s population.

This is all the more remarkable given that as recently as 1820, according to economist Michail Moatsos, three-quarters of the world lived in extreme poverty, meaning that they “could not afford a tiny space to live, some minimum heating capacity, and food that would not induce malnutrition.”

Clearly, humanity has the ability to leverage economic growth and significantly reduce extreme poverty.

This positive trend will likely continue, given the microfinance programs in place, such as the one launched by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, who pioneered the use of small loans at affordable interest rates in an effort to transform the lives of the impoverished.

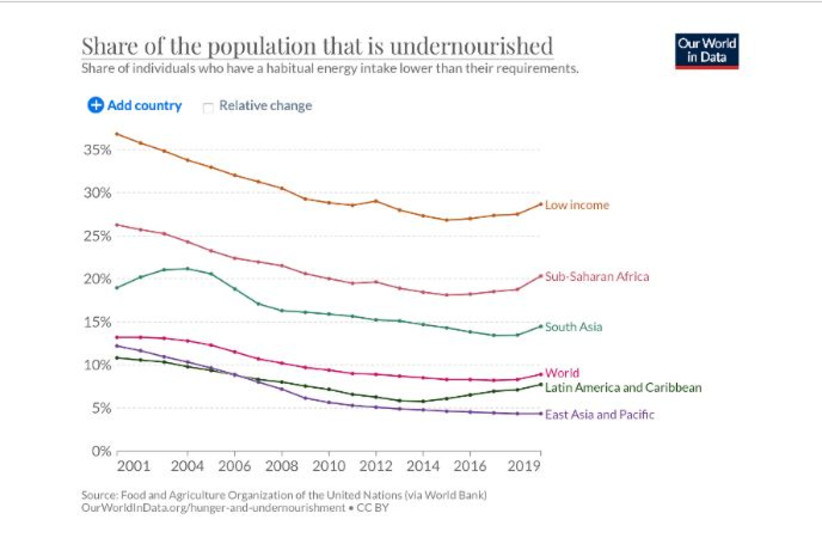

2. Hunger is diminishing

Currently, 663 million people – 8.9% of the world’s population – are undernourished. In 2001, that number was 13.2%. Unfortunately, we lack long-term historical data on hunger and malnourishment. The most concrete measurements began in 1990, and some go back as far as 1970. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations says that in 1970, nearly 35% of the developing world was undernourished. Today’s figures show a clear downward trend.

As the population increases to 10 billion people in 2050, the demand for meat will double. Our increased appetite presents four key challenges: human health, climate change, natural resources, and animal welfare.

Humans will not need to make a decision on whether to eat or abandon meat, but we will need to consider the origin of our “meat.” If we choose poultry, pigs and cows, then our choices are limited. If, on the other hand, we define meat by its composition and chemical structure, then we have unlimited solutions. Through science, technology and innovation, we can make use of plants and transform their basic architecture to provide meat substitutes.

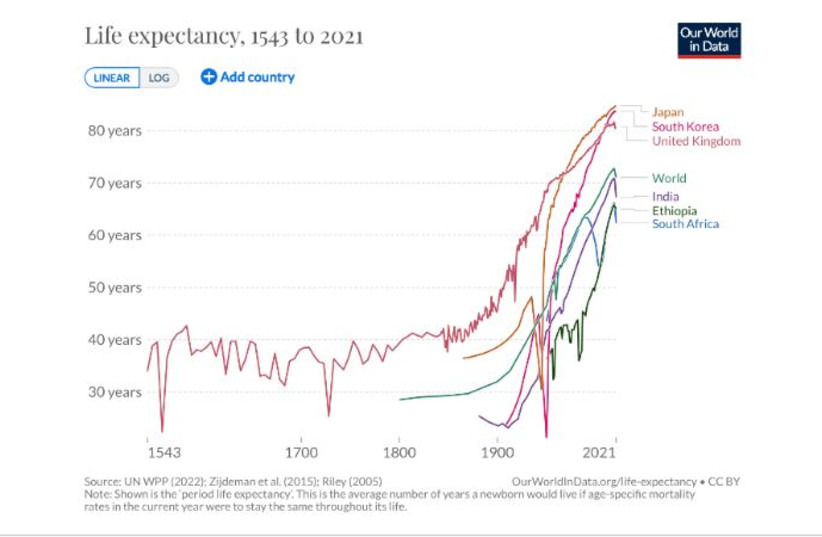

3. Life expectancy is rising

In 1800, worldwide life expectancy was 28.5 years. By 2021, that number had risen to 72.6 years, and in the world’s richest countries, to well over 80 years. The gap between the lifespans of the richest and poorest countries continues to be closed, including, notably, in Africa and Asia.

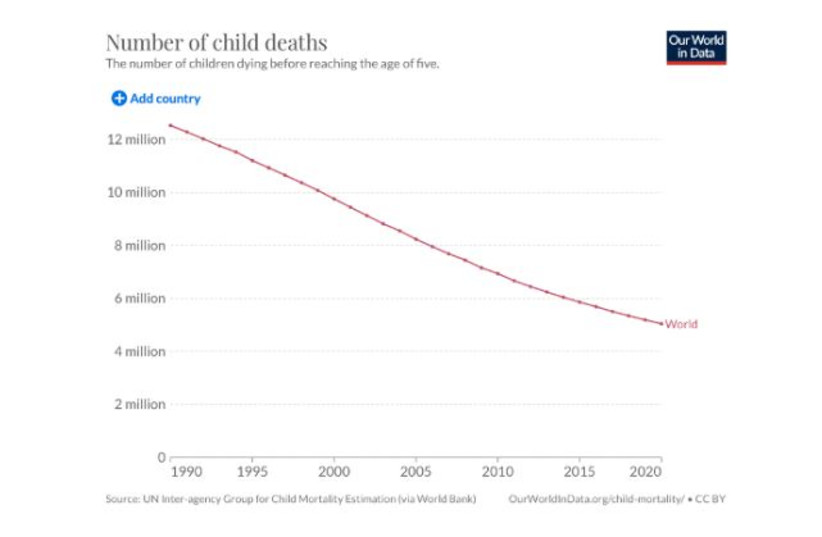

4. Child mortality is down

We are now experiencing the world’s lowest child mortality rate – defined as the share of newborns who die before the age of five – in the history of humanity. In the last three decades alone, the number has been halved, from 12.5 million in 1990, to 5.2 million in 2019. In two of the world’s most populous countries, the decline is even more staggering: In 1969, China’s child mortality rate was 11.84%, and in 2020, 0.73%; while in India, the rate in 1960 was 24.26%, compared to 3.26% in 2020.

To place this in historical context, in 18th-century Sweden, every third child died; and in 19th-century Germany, every second child died. In 1960, the global child mortality rate was 19%.

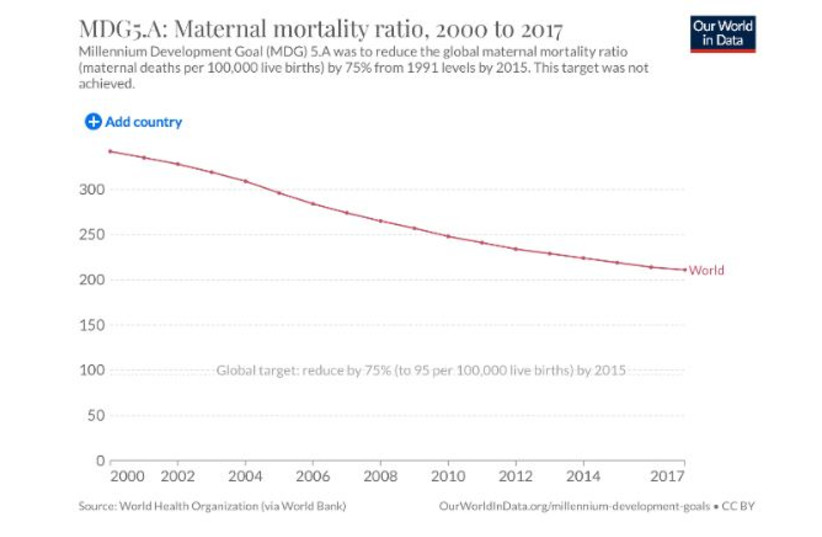

5. Death in childbirth is declining

For almost all of human history, pregnancy and childbirth were dangerous, and mothers and children faced a significant chance of death. But that number has come down precipitously in the last few centuries and significantly in the last 20 years.

In 2000, there were 450,800 maternal deaths worldwide (with a population of just over six billion), versus 293,760 in 2020 (with a population of nearly eight billion).

To put this in perspective, in 1800 in Sweden and Finland, around 900 of every 100,000 mothers died in childbirth; in today’s numbers, that would be 1.26 million of the eight billion people on the planet.

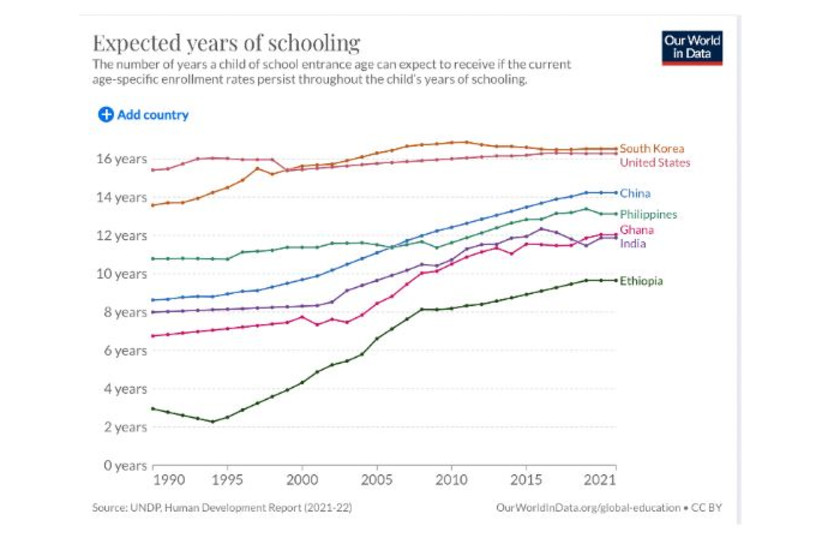

6. Students are staying in school longer

The trend in average years of schooling across 111 countries is impressive. In 1870, the average for the vast majority of countries was less than a year. Today, it is over 12 years of schooling for the wealthy industrialized countries, and in places like Kenya and India, 6.5 years.

There is clearly more work to do, but the increase is impressive – and will likely continue, with free online education programs like the Khan Academy (http://www.khanacademy.org), a platform that provides a free, world-class education for anyone, anywhere.

The platform offers math, science, computing, history, art history, economics and more, including K-14 and test preparation content (SAT, Praxis, LSAT). The content focuses on skill mastery to help learners establish strong foundations, so there’s no limit to what they can learn. Khan Academy has already translated its videos into over 30 languages.

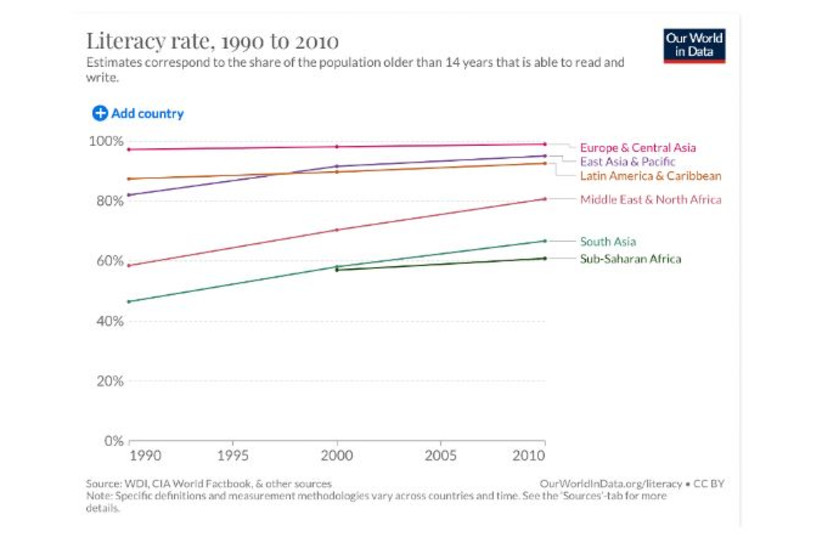

7. Literacy is increasing

In 1800, the global literacy rate for people 15 years and older was 12.05%, while in 2016, 86% of those in this age bracket were literate. There are still inequalities, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa, specifically Burkina Faso, Niger and South Sudan, where literary rates are below 30%. But this historic change should not be underestimated.

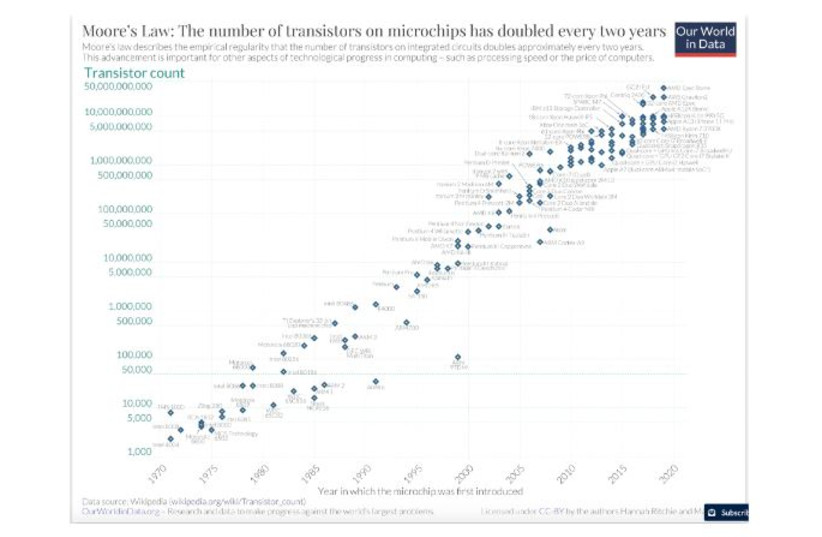

8. Moore’s law has thus far proven true

More than half a century ago, Gordon Moore proposed a theory that would radically change our conception of technology.

The power of microchips running our computers, he predicted, would double every two years, while their cost would remain about the same. He predicted the invention of home computers, cellphones, self-driving cars, and smartwatches – all of which would become less expensive over time.

Moore’s law has since proven to be true. Some claim that this trend cannot continue, given limitations on how many transistors can fit on a chip. Others, however, believe that computer power can continue to grow exponentially.

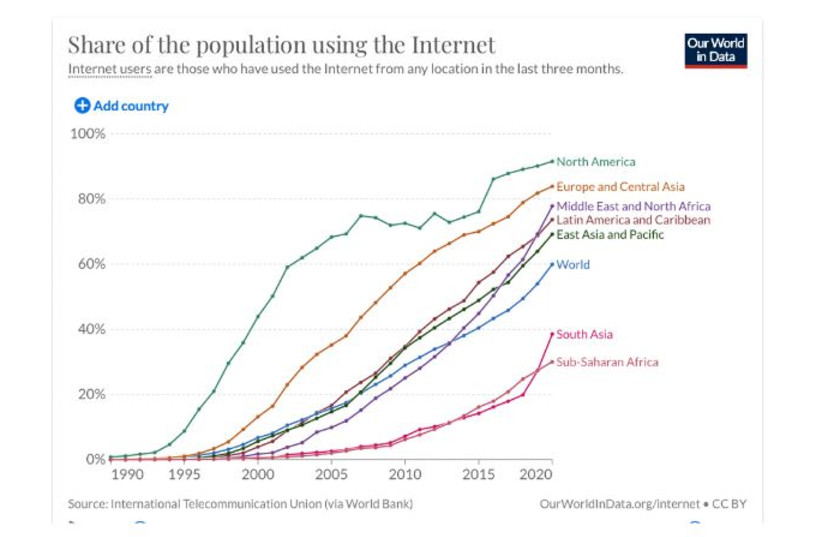

9. Internet access is increasing

The share of the population that is accessing the Internet is increasing, including in the developing world. More than two-thirds of the population of wealthier countries is online. Around half of the world’s population is not yet online, which means the collective power of the Internet will likely increase in the years ahead.

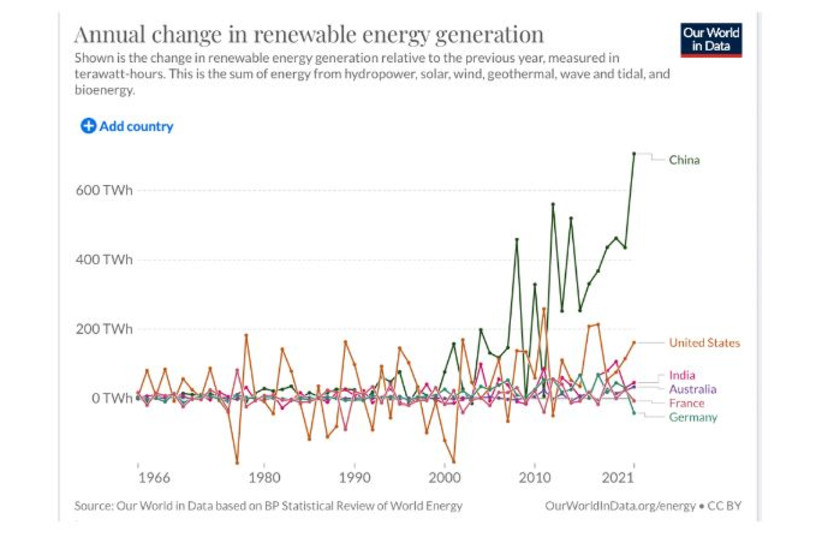

10. Use of renewable energy is increasing

Fossil fuels, which have a major impact on the Earth’s climate, have dominated the energy mix of most countries for decades. They are responsible for the vast majority of greenhouse emissions and cause significant air pollution, affecting human health.

To reduce the world’s carbon footprint, a significant turn toward renewable energy will be necessary. In 2019, nearly 8,000 terawatt-hours, or roughly 11% of global energy use, came from renewable technology, which includes hydropower, solar power, wind power, geothermal wave power, tidal power and modern biofuel. In 1965, in contrast, global production of renewable energy was only 941 terawatt-hours.

IF WE’RE going to meet the challenges of this century – from climate change to food scarcity – governments, companies and entrepreneurs from around the world will need to work together and use the type of bold, creative thinking that got us to the moon.

“Moonshots live in the gray area between audacious projects and pure science fiction.”

Eric “Astro” Teller

As explained by Eric “Astro” Teller, the director of Google X, a research and development facility that creates radical new technologies, “Moonshots live in the gray area between audacious projects and pure science fiction.” A moonshot, he asserts, is “almost more an exercise in creativity than it is in technology.”

Governments are no longer the only entities that can play a meaningful role in tackling these seemingly intractable challenges. Corporations, research institutions, and do-it-yourself innovators with few resources and little manpower, alongside techno-philanthropists like Bill Gates, who are spending billions of dollars of their own wealth, can now achieve moonshots on their own.

The transformation the world is currently undergoing is profound and will far supersede the impact of the Industrial Revolution. What’s next? The future belongs to those who choose hope – and those who leverage technology to positively affect humanity.

The writer (www.avijorisch.com) is the author of NEXT: A Brief History of the Future (Gefen Publishing; reviewed in the Magazine Feb. 17) and a senior fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council.