A bite of food is about more than calories. Food production involves energy, water, and other resources and is shaped by economics, policies, and international relations. What we eat affects our health, expresses our cultures, and shapes communities.

Feeding the world is an urgent challenge: In 2023, the United Nations reported that one in 11 people globally faced hunger, with 2.33 billion people facing moderate or severe food insecurity. These disparities in food access and malnutrition lead to a cascade of other problems.

Stanford’s history with food research stretches back to the founding grant’s mention of “the study of agriculture in all its branches.” From 1921 to 1996, the Stanford Food Research Institute, inspired by Herbert Hoover, led globally influential research on food systems.

Today, Stanford remains well-positioned to influence the way the world grows, distributes, eats, and thinks about food. Threads of food research and teaching run throughout the university, crossing disciplines and schools, including the work of dozens of faculty members. This is complemented by interdisciplinary and solution-focused efforts established to coordinate this work.

“Interdisciplinary research can help us understand how each disciplinary contribution fits into the bigger picture of global food security. Through such collaboration, advances are also made on basic research questions within disciplines,” said Rosamond Naylor, professor of environmental social sciences in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability, who was also founding director of the Center on Food Security and the Environment (FSE), a joint effort of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) and the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

Adaptive plants, agriculture – and aquaculture

Understanding plants is foundational to improving global food systems – and that means studying the building blocks of food from many angles.

For her part, Elizabeth Sattely, an associate professor of chemical engineering in the School of Engineering, investigates plant chemistry. Her lab explores how plants transform carbon dioxide and sunlight into molecules that bolster their resilience to environmental stress and can benefit human health. Her work holds promise for developing crops capable of withstanding the pressures of climate change and disease – and has inspired her to facilitate stronger collaborations between Stanford food researchers to address specific problems within our food system. (More on that later.)

“Crop losses to disease remains stubbornly high, and improving the nutrient profile and climate tolerance of staple crops would have a massive effect on global nutrition,” said Sattely. “We need folks who think about all the different facets of food systems to come together to find high-impact solutions that are equitable and sustainable.”

Sattely frequently partners with Mary Beth Mudgett, a professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences (H&S), who studies plant immune responses to pathogens and the chemical signals plants use to communicate. Knowing what happens inside and among plants can inform research in other food-related fields, Mudgett said. For example, details about plant immune responses can help prevent plant diseases among crops.

The Sattely lab works to reveal how plants use their chemistry to grow into the largest and longest-living organisms on Earth. They aim to use this knowledge to engineer plant proteins and metabolites in a way that will make agriculture more sustainable and prevent human diseases caused by diet. | Courtesy Stanford Engineering

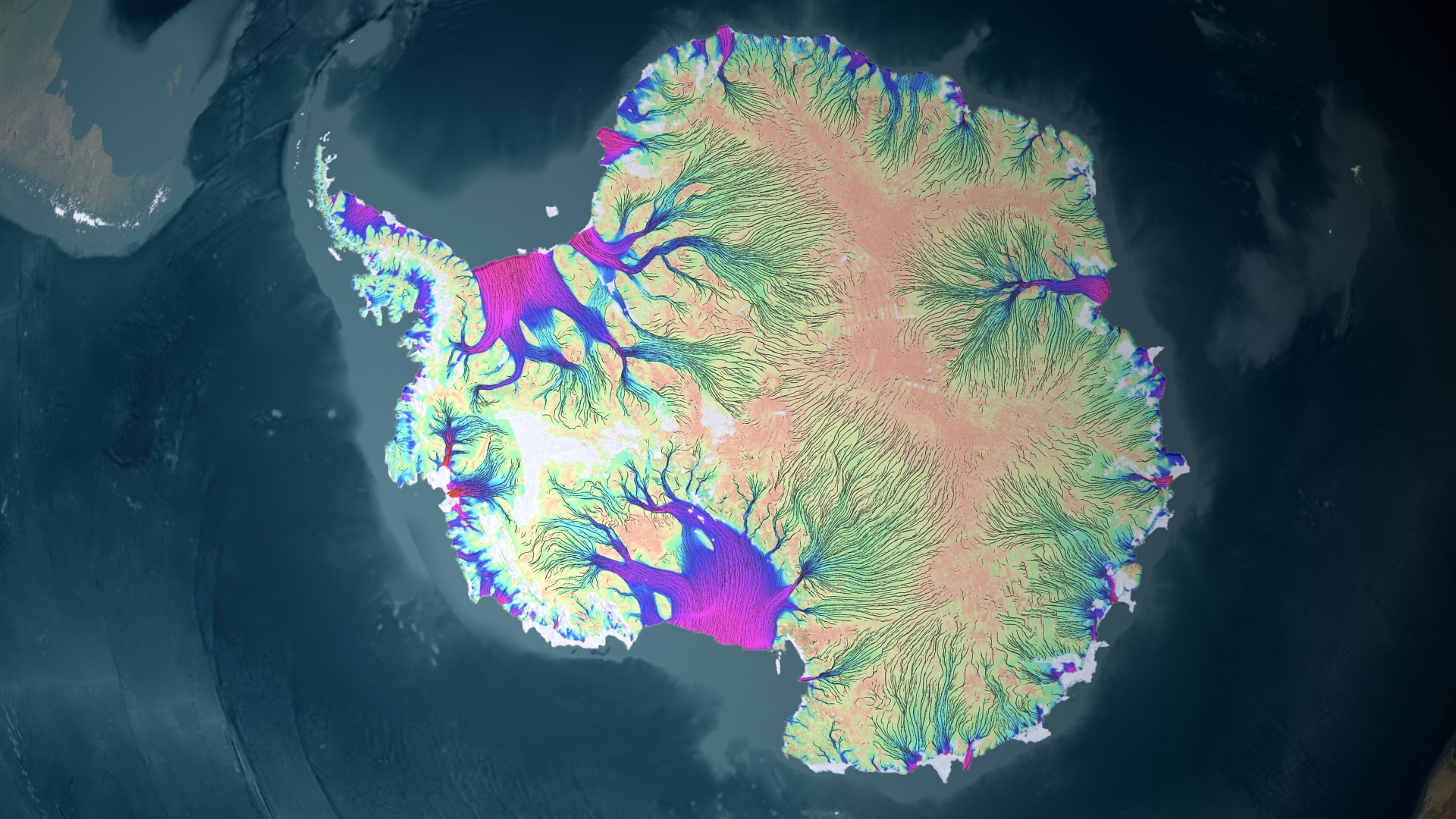

At a broader scale but following the same theme, David Lobell, professor of Earth system science in the Doerr School of Sustainability, uses remote sensing to evaluate the effectiveness of climate change adaptations in agriculture. His lab’s detailed farm-level data provides critical insights into practices like cover cropping, which protects and enriches soil but can come with environmental downsides such as reduced land productivity.

“We get a much better understanding of where things work, which helps to scale up successful things and avoid promoting and incentivizing things that aren’t working,” said Lobell, who is also the current director of FSE.

Responsible food production must also account for affordability and nutrition, not just caloric abundance. Naylor points out that people without access to a nutritious diet are more likely to overuse resources and destroy biodiversity just to survive, she said. Lack of food security also compromises health and reduces equity in general. Even in low and middle-income countries, poor diets contribute to serious health problems like diabetes.

“Food security and nutrition has tentacles in every aspect of society,” she said.

One focus of Naylor’s work is integrating aquatic foods – such as fish and seaweed – into sustainable food systems, expanding options beyond traditional crops and livestock. She co-chaired the international Blue Food Assessment in 2019 and continues to explore sustainable aquaculture development in regions like Indonesia and Kenya.

“In the past, we’ve only thought about crops and livestock when we think about food systems, but we also need to think about fish and seaweeds and aquatic plants and put those into the frame,” she said.

Naylor is among the faculty affiliated with the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions (COS), which advances understanding of ocean-related challenges and develops solutions. COS’s work includes blue food topics like nutrition, sustainability, and climate. One initiative addresses illegal fishing and labor abuses at sea, including the health and well-being of fisheries workers in the face of a warming world – also an area of concern for agricultural workers, who face exposure to extreme heat.

Food is also one of eight areas of focus for the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability’s efforts to generate knowledge and create solutions that help people and nature thrive. This includes support through the school’s Sustainability Accelerator to rapidly translate Stanford research into practical applications that dramatically reduce emissions from food and agriculture by 2035. For example, one Accelerator project aims to launch a low-cost, less energy-intensive alternative to industrial fertilizers for small farms.

Snapshots of more Stanford food research

The human element

People are at the heart of the food system as laborers, consumers, experts, and, of course, the entities controlling how the system works. Food can be a profession, but it’s also personal, in terms of culture, health, and impacts on the functioning of society.

Lisa Goldman Rosas, an assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Population Health and in the Department of Medicine at Stanford Medicine, leads the Food For Health Equity Lab. The lab partners with community food distributors to address food insecurity and diet-related health issues. One program, Vida Sana y Completa, provides culturally tailored, diabetes-friendly foods to Latina women through Second Harvest Food Bank. The researchers track outcomes like weight loss and quality of life to inform policy and programming.

“Food insecurity is a persistent problem with significant disparities across our country, and it’s getting worse,” Goldman Rosas said. “Making a difference by generating evidence that community health centers and food banks can actually use to drive their programs and policies is important to us.”

Vayu Hill-Maini, an assistant professor of bioengineering in the schools of Engineering and Medicine who joined Stanford faculty in fall 2024, is building a research group that seeks to bridge science, gastronomy, sustainability, and health. As a biochemist, synthetic biologist, and former chef, Hill-Maini uses fungi and fermentation to design new healthy, sustainable foods. His lab will also have a kitchen modeled on the world-class restaurants where Hill-Maini previously worked.

“Transforming the food system isn’t just about sustainability,” he said. “It has to be tasty and connect to us as humans from a cultural, sensory, psychological perspective.”

Stanford faculty are also incorporating Indigenous knowledge, culture, and practice into food research and scholarship. This includes connecting students with Indigenous food researchers, advocates, and thinkers through collaborative work and distinctive courses.

Rodolfo Dirzo, a professor of biology in H&S and of Earth system science in the Doerr School of Sustainability, led a 2023 Bing Overseas Studies Program Global Seminar in Oaxaca, Mexico, where students experienced that region's biocultural diversity and conducted research with local scientists. On campus, Stanford lecturer A-dae Briones teaches Tribal Food Sovereignty, which explores Indigenous food systems.

As part of the Global Seminar on biocultural diversity and community-based conservation in Oaxaca, students took part in an ecological survey assessing the health of copal trees and met with the environmental and agricultural conservation organization, Palo Que Habla. | Andrew Brodhead

Agricultural systems often discount how tribal people think about food – but Indigenous people have unique insights into ideas like sustainability and regenerative farming, said Briones, the vice president of research and policy at the First Nations Development Institute.

“The lessons and the collected knowledge over generations are not being utilized in ways to help our global community wrestle with some of these issues,” she said. “I think a lot of answers to some of our most pressing problems around climate change and agricultural damage can be found with Indigenous people in the room.”

A new era of collaboration

Taking full advantage of a campus with myriad resources, residences, and labs, interdisciplinary collaboration is central to Stanford’s approach to food research.

Residential Dining and Enterprises created the R&DE Stanford Food Institute, which unites students, faculty, staff, producers, chefs, and entrepreneurs from many disciplines. Their goal is to promote a holistic approach to improving what people eat, how people access food, and the role that food plays in our lives. The Stanford Food Institute brings evidence-based, equitable, climate-focused food solutions to the Stanford community.

In addition to other work, the institute uses campus dining halls to see how people make food choices in the real world – from the perspective of the people who put the food on our plates – and they hope their efforts can inform changes that benefit the world.

A developing initiative helmed by Sattely, called Food Futures, aims to unite cross-disciplinary researchers to come up with “solutions that will enable equitable, sustainable, and nutritious food for humanity.” Food Futures focuses on creating detailed problem statements to guide actionable solutions, engaging faculty and students across disciplines through research, symposiums, and courses. The efforts will specifically focus on tractable issues – those that are potentially near to being solved, if given the right investments and expertise. Examples could include access to healthy food in low-income areas, herbicide resistance, soil health, and water use in agriculture in developing countries.

“Stanford doesn’t have an agronomy department or plant breeding, but we have tons of smart people who know how to work together and are willing to learn a whole new vocabulary,” said Virginia Walbot, a professor emerita of biology in H&S who is in the Food Futures working group. “People want to tackle large, significant problems.”

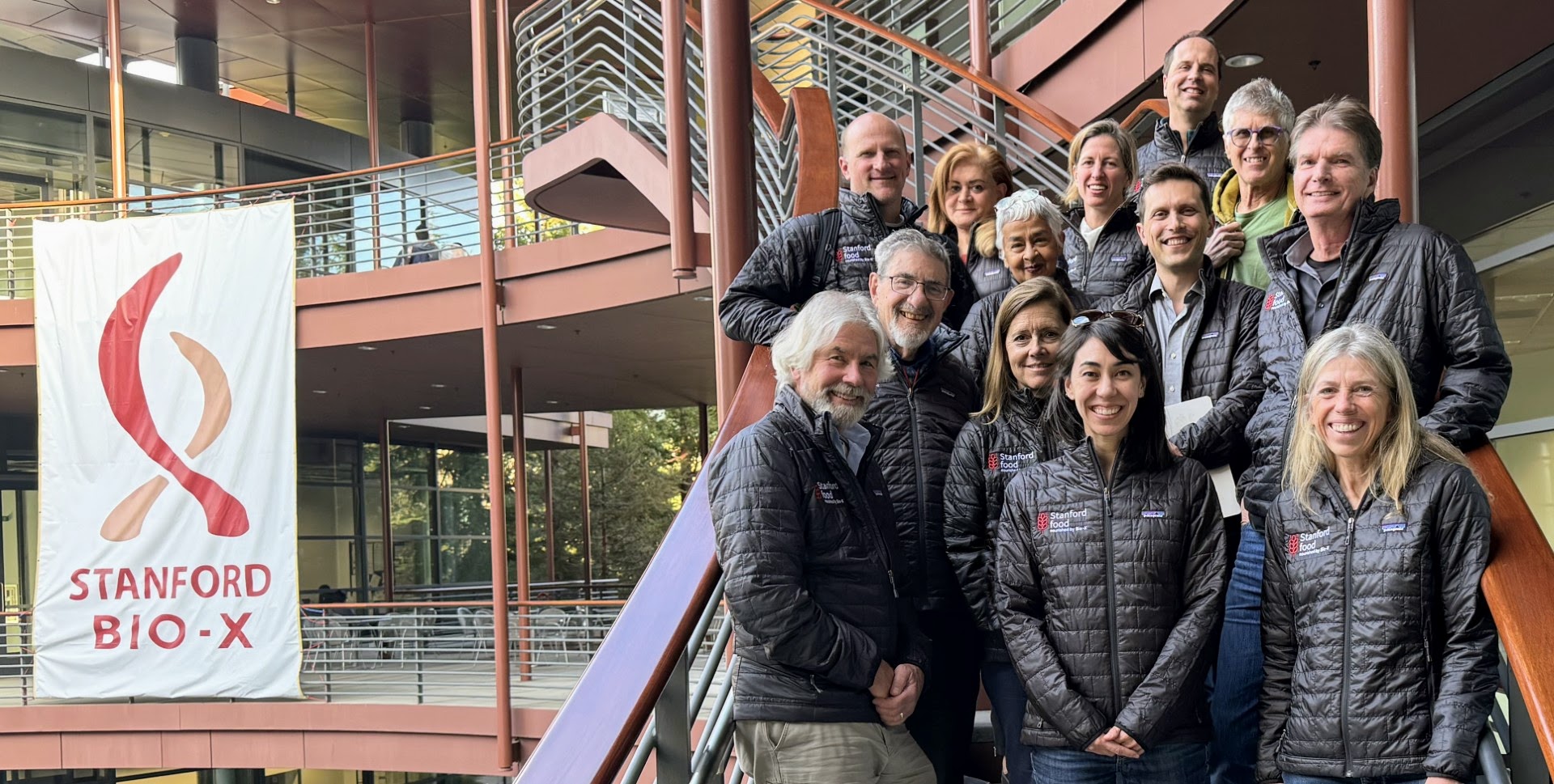

“A person who studies climate change has no access to the molecular, cellular, or chemical events that happen in your gut when you eat something, and the gut person doesn’t know the policy it takes to really implement change. The idea that Beth and I share is that we want to bring people together to solve these big challenges with a holistic view,” said Ellen Kuhl, professor of mechanical engineering in Stanford Engineering who uses AI to improve plant-based meat alternatives. As the director of Stanford Bio-X, she has partnered with dozens of faculty to launch the campus-wide initiative Food@Stanford with the inaugural one-day symposium Rethinking Food From Plate to Planet.

Faculty and staff involved in the Food@Stanford effort, supported by Stanford Bio-X. Back row: Markus Covert, Heideh Fattaey, Elizabeth Sattely, Jonas Cremer, Pat Brown. Middle row: Richard Zare, Devaki Bhaya, Benjamin Good, Alfred Spormann. Front row Christopher Gardner, Mary Beth Mudgett, Jennifer Brophy, Ellen Kuhl. | Heideh Fattaey

Changing the food system won’t be fast or easy. But these researchers are aware that efforts at Stanford have the potential to change how other people and institutions talk and think about food and agriculture. “When we think about the power that Stanford has in influencing systems in America – whether in technology or capitalism – it’s clear that Stanford has a huge influence that trickles down to many other parts of the country,” said Briones.

By drawing on diverse expertise and valuing collaborative efforts, Stanford is building innovative solutions to the world’s most pressing food challenges. “We can look at the world differently and draw upon the expertise that we have in business, engineering, sustainability, and policy to take a different stab at it,” Hill-Maini said. “From my viewpoint, food research in academia has been a wasteland of innovation. Stanford, I think, can change that.”

Read more

For more information

Dirzo is also associate dean for integrative initiatives in environmental justice, the Bing Professor in Environmental Science in the Doerr School of Sustainability, and senior fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment. Goldman Rosas is also a member of Bio-X, the Maternal & Child Health Research Institute (MCHRI), the Stanford Cancer Institute. Kuhl is the Catherine Holman Johnson Director of Stanford Bio-X and the Walter B. Reinhold Professor in the School of Engineering. She is also a member of Bio-X, the Cardiovascular Institute, the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance, the Institute for Computational and Mathematical Engineering, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Lobell is the Benjamin M. Page Professor at Stanford University in the Department of Earth System Science and the Gloria and Richard Kushel Director of the Center on Food Security and the Environment. He is also a senior fellow at FSI, the Woods Institute, and the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR), an affiliate of the Precourt Institute for Energy, a member of Stanford Data Science, and faculty director of Sustainability Data Science. Mudgett is also the senior associate dean for the natural sciences and the Susan B. Ford Professor in H&S, the Stanford Friends University Fellow in Undergraduate Education, and a member of Bio-X. Naylor is also the William Wrigley Professor of Global Environmental Policy in the Doerr School of Sustainability, a senior fellow of FSI and the Woods Institute, and a senior fellow at FSE. Sattely is also a member of Bio-X and a faculty fellow of Sarafan ChEM-H.

Writer

Tara Roberts