How agriculture has become central to the China-US trade war

The Chinese retaliatory tariffs have not been sweeping and across-the-board. But even while selective, they have hit where it hurts the most.

US President Donald Trump has exempted many goods from the 25% tariff imposed on Canada and Mexico, but provided no such relief for China (Reuters)

US President Donald Trump has exempted many goods from the 25% tariff imposed on Canada and Mexico, but provided no such relief for China (Reuters)In his trade wars with Canada and Mexico, US President Donald Trump has exempted many goods from the blanket 25% tariff he had earlier levied on all imports from the two countries.

Thus, the 25% additional import duty will not be applicable on goods covered under the United State-Mexico-Canada Agreement. That would automatically spare some 50% of Mexican and 38% of Canadian imports qualifying for preferential treatment under this trade agreement. Further, imports of energy products from Canada and potash fertiliser from both countries are to attract only 10% tariff.

However, no such partial rollbacks have been made when it comes to imports from China. On February 4, Trump effected a 10% additional tariff on all Chinese goods, which was doubled to 20% from March 4. Simply put, the trade war with China has only seen escalation and no tariff exclusions or pauses. Neither side has shown willingness to negotiate so far.

The Chinese retaliation

China’s tit-for-tat actions have basically targeted US agricultural produce. On March 4, it imposed a 10% tariff on imports of soyabean, sorghum, beef, pork, dairy and aquatic products, fruits and vegetables, and 15% on wheat, corn (maize), cotton and chicken, from the US.

These additional duties — a response to the “unilateral tariff increase by the US” that “undermines the multilateral trading system…and disrupts the foundation of China-US economic and trade cooperation” — aren’t insignificant.

In 2024, China’s imports of agricultural and related products from the US were valued at $27.29 billion. That included soyabean ($12.76 billion), beef ($1.58 billion), cotton ($1.48 billion), pork ($1.11 billion), seafood ($1.02 billion), dairy ($584 million), poultry meat ($490.1 million), wheat ($556.9 million), corn ($327.9 million) and other coarse grains ($1.26 billion).

Table.

Table.

The Chinese retaliatory tariffs have not been sweeping and across-the-board. But even while selective, they have hit where it hurts the most. The US farming heartland — from the Midwestern soyabean-corn-wheat growing states to the Southern cotton belt —is already feeling the effects. As Chuck Conner, head of the US National Council of Farmer Cooperatives, was quoted by NBC News: “Any time there is a trade dispute with another country, they recognise that our soft underbelly… is when you start messing with our food exports”.

Change in strategy

But China’s tariff actions also appear to fit in with a national strategy to enhance food security through increasing domestic production and reducing import dependence alongside diversification of its supplier base.

China is a massive importer of agri-commodities. In 2023-24, it was the world’s No. 1 buyer of soyabean, rapeseed, wheat, barley, sorghum, oats and cotton, and No. 2 for corn and palm oil. It was also the biggest export market for US soyabean, cotton and coarse grains (excluding corn), while the second largest for its tree nuts (mainly almonds, pistachios and walnuts) and third for beef, pork, dairy products and poultry meat.

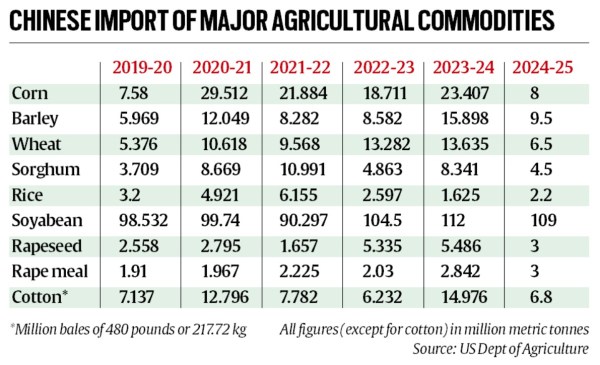

To give an idea of how much China imports, take soyabean. Last year, it imported 112 million tonnes (mt) of this oilseed. This was apart from 23.4 mt of corn, 15.9 mt of barley and 13.6 mt of wheat. India, by comparison, is a major importer of only vegetable oils (16 mt, including 9 mt of palm, 3.5 mt of sunflower and 3.4 mt of soyabean) and pulses (4.7 mt).

China has two state-owned giants: COFCO (China Oil and Foodstuffs Corporation) and Sinograin (China Grain Reserves Group). The first one is a global trader that handled over 122 mt of agri-commodities with revenues of $50 billion in 2023. COFCO has been promoted as a rival to the four ‘ABCD’ dominant western commodity trading firms: Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus. Sinograin, established in 2000, is China’s national stockpiler tasked with the storage and management of its centralised reserves of grain, oil and cotton.

China, which began augmenting its strategic reserves following the 2008 global food price crisis, substantially stepped up imports of corn, barley, wheat, sorghum and even oilseeds, cotton and rice from 2020-21 (see accompanying table). The unprecedented import-led stockpiling — amid the pandemic, Russia-Ukraine war and extreme weather-induced worldwide supply disruptions —was undertaken through COFCO and Sinograin.

Focus on self-reliance

But the above strategy has seemingly undergone a shift in the last couple of years.

In April 2023, the Chinese Ministry of Agricultural and Rural Affairs unveiled a report that projected an increase in the country’s domestic output of grains (including soyabean) from 694 mt to 767 mt and a reduction in imports from 148 mt to 122 mt by 2032.

The emphasis on achieving food security by boosting domestic production and cutting reliance on imports — similar to India’s atmanirbharta programme — came even as President Xi Jinping stated that “Chinese people should hold our rice bowls firmly in our own hands, filled with grains mainly produced by ourselves”.

The US Department of Agriculture has projected sharp slides in China’s imports of wheat, corn, barley, sorghum and rapeseed for the 2024-25 marketing year (July-June).

In the case of soyabean, imports — which are processed for oil and the residual protein-rich cake (meal) fed to the world’s biggest swine population and one of its largest poultry flocks — aren’t expected to fall much. But US share of China’s soyabean imports has declined from 30% in 2017-18 to 22% in 2023-24, while rising from 62% to 71% from Brazil. In value terms, China’s imports of US corn and soyabean peaked at $5.21 billion and $17.92 billion in 2022 respectively, and been on a downward trajectory since, with more of the grain coming from Brazil and Argentina.

These trends may only gather momentum with an intensification of the trade war between the world’s two biggest economies. And to what extent it would put pressure on India to “open up” its market to US farm produce remains to be seen.

More Explained

Must Read

EXPRESS OPINION

Mar 17: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05