China’s exploitation of overseas ports and bases

Introduction

This paper examines the potential for the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to exploit its growing network of overseas ports and bases to challenge control of the seas in a conventional war with the United States. Security concerns with Chinese ownership of overseas ports fall into three main categories. First, China collects vast amounts of intelligence via its port network. Second, it could use that intelligence and its control of key ports and piers to disrupt US shipments during wartime. Finally, China could leverage these ports to pre-position weapons, ammunition, and equipment to resupply its warships and armed merchants or rapidly establish anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) nodes near major maritime choke points. In short, China could exploit this network to challenge the sea control essential to US success in an armed conflict.

This paper does not speculate on why the United States and China might enter a global conflict. In fact, current Chinese writings indicate China does not seek a global confrontation. Rather, Chinese strategic literature reflects a preference for winning without fighting and, if forced to fight, fighting one local enemy at a time after politically isolating that enemy.

As with all future papers, this one starts with assumptions. It then examines China’s current network of overseas ports and its expansion of that network. The rationale behind China’s pursuit of overseas ports is explored through an analysis of Chinese strategic vulnerabilities. This paper considers three potential applications for these bases, including an improbable worst-case scenario, to assess how China may exploit this advantage.

After evaluating China’s potential actions, the paper examines possible US responses and concludes with recommendations for the capabilities, training, organization, and equipment necessary to execute those missions effectively.

Assumptions

Assumptions are critical to planning. They provide guidance concerning essential but inherently unknowable factors required to initiate planning.1DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, March 2017), https://www.tradoc.army.mil/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/AD1029823-DOD-Dictionary-of-Military-and-Associated-Terms-2017.pdf. The following assumptions are key to assessing China’s potential use of overseas bases and ports in a conflict with the United States.

Assumption 1: The war will be long.

By the time the modern state and its military institutions fully emerged at the end of the seventeenth century, wars were won or lost on the ability of financial and economic systems to sustain and support armies in the field and navies at sea.2Williamson Murray, The Dark Path: The Structure of War and the Rise of the West (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2024), 7.

Since 1750, conflicts between healthy, major powers lasted years to decades, even though national leaders often assumed they would be short. The Seven Years’ War, the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, the US Civil War, the First and Second World Wars, and the Russo-Ukrainian War lasted between three to twenty-three years.

War games have repeatedly shown that the United States would run out of critical munitions just eight days into a high-intensity conflict with China over Taiwan.”3Wilson Beaver and Jim Fein, “The U.S. Needs More Munitions To Deter China,” Heritage Foundation, December 29, 2023, https://www.heritage.org/defense/commentary/the-us-needs-more-munitions-deter-china. However, this does not mean a war with China would be short. In both the US Civil War and the First World War, ammunition shortages reduced the intensity of fighting for up to a year. Yet, both sides mobilized their industries and replenished ammunition stocks even as they raised massive armies. These wars continued for years after the combatants overcame their initial shortages. The current Russo-Ukrainian War follows this pattern.

These long wars have ended in one of two ways: a negotiated treaty or the destruction of the enemy’s forces and subsequent occupation of its homeland. Economic exhaustion of one or both parties was a key factor in these conflicts.

However, nuclear weapons introduced a new factor that makes occupying a nuclear-armed power a highly dangerous proposition. Andrew Krepinevich, Jr., president and chief operating officer of Solarium LLC, a defense consulting firm, notes:

- [W]ith the advent of nuclear weapons, wars between great powers can be protracted only if political constraints are imposed on vertical escalation.4Andrew F. Krepinevich, Jr., Protracted Great-Power War: A Preliminary Assessment, Center for New American Security, February 5, 2020, 1, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/protracted-great-power-war.

The presence of nuclear weapons appears to rule out a strategy of annihilation or large-scale attacks on either combatant’s homeland. Instead of seeking a decisive victory, the United States and China would likely pursue a strategy of exhaustion, pitting their economic and fiscal systems against each other. In this conflict, sea control would be critical.

Assumption 2: China is establishing a mix of overseas military bases, ownership of overseas commercial ports, and access to other nations’ commercial ports.

Chinese entanglement in foreign bases and ports is not an assumption but a reality. The only uncertainty is which facilities China could access in a conflict. In 2018, Ely Ratner, at the time the Maurice R. Greenberg senior fellow for China studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, noted, “China’s government is actively searching for overseas bases.”5Ely Ratner, Geostrategic and Military Drivers and Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative, Council on Foreign Relations, January 25, 2018, https://www.cfr.org/report/geostrategic-and-military-drivers-and-implications-belt-and-road-initiative. Since then, China has continued to invest heavily in overseas facilities.6Zongyuan Zoe Liu, “Tracking China’s Control of Overseas Ports,” Council on Foreign Relations, updated August 26, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/tracker/china-overseas-ports.

Assumption 3: China is developing fully autonomous uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs), uncrewed surface vessels (USVs), and uncrewed underwater vessels (UUVs).

Currently, several nations deploy weapons capable of autonomously hunting targets post-launch.7“How Ukraine uses cheap AI-guided drones to deadly effect against Russia,” Economist, December 2, 2024, https://www.economist.com/europe/2024/12/02/how-ukraine-uses-cheap-ai-guided-drones-to-deadly-effect-against-russia. China, already a leader in drones and autonomy technologies, will undoubtedly operate post-launch autonomous drones across air, land, and sea domains within a few years. As the Houthis have demonstrated, even a small number of inexpensive drones can challenge current US Navy capabilities. China has the potential to produce these in the millions.8Olena Harmash, “Ukraine ramps up arms production, can produce 4 million drones a year, Zelenskiy says,” Reuters, October 2, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraine-ramps-up-arms-production-can-produce-4-million-drones-year-zelenskiy-2024-10-02/.

Assumption 4: China could execute a plan using its Chinese-owned overseas ports and bases with its current capabilities.

The PLA already possesses the capabilities required to exploit Chinese bases and Chinese-owned overseas ports. The key will be China’s willingness to think differently and commit forces to missions with a slight chance of those forces returning.

Assumption 5: The United States cannot predict which nations will allow US forces to operate from their territories during a war. Therefore, the United States must plan for various permissions and structure future forces accordingly.

International relations in the Indo-Pacific are in flux. While many analysts believe Australia and Japan will allow US forces to use their territory in a conflict with China, there is much less confidence regarding the positions other nations in the region will take. In the last few years, China has pulled back from its “wolf-warrior” approach to diplomacy and refocused its Belt and Road Initiative. This may lead Pacific nations toward neutrality or even alignment with China.

Chinese overseas port posture

Numerous studies have examined China’s rapid and ongoing expansion of ownership or management of ports globally. Most provide detailed analyses of why China is seeking a global footprint, and several papers also analyze China’s reasoning for selecting specific ports.9Christina L. Garafola, Stephen Watts, and Kristin J. Leuschner, China’s Global Basing Ambitions: Defense Implications for the United States, RAND Arroyo Center, December 8, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1496-1.html.

However, there is no consensus on precisely which facilities China will own or have access to. All studies note China’s naval base in Djibouti. More recently, Newsweek reported that China continues to expand naval facilities in Ream, Cambodia.10Aadil Brar, “Chinese Warships Permanently Deployed at New Overseas Naval Base,” Newsweek, April 26, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/china-cambodia-ream-new-permanent-naval-base-1894012. The Washington Post reported China continued its efforts to establish “military facilities at the United Arab Emirates port of Kalifa.”11Liz Sly and Julia Ledur, “China has acquired a global network of strategically vital ports,” Washington Post, November 6, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/interactive/2023/china-ports-trade-military-navy/. RAND rated four countries—Cambodia, Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Pakistan—as highly desirable and feasible candidates for subsequent naval bases.12Garafola, Watts, and Leuschner, China’s Global Basing Ambitions, 11.

Isaac B. Kardon and Wendy Leutert note that “the [People’s Liberation Army Navy] enjoys privileged access to dual-use facilities that Chinese firms own and operate.”13Isaac B. Kardon and Wendy Leutert, “Pier Competitor: China’s Power Position in Global Ports,” International Security 46, no. 4 (2022): 10, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00433. This means Chinese personnel could oversee the day-to-day operations at these terminals. Chinese firms “hold an equity stake in the lease or concession on at least one terminal in ninety-six foreign ports.”14Kardon and Leutert, “Pier Competitor.” Forty-five of the ninety-six ports lie along significant sea lines of communications (SLOCs) critical to Chinese imports and exports. Fifty-five percent of the ports are within 480 nautical miles (one steaming day) of critical choke points on these SLOCs. While China may focus on protecting its SLOCs, these routes are essential to the global economy. Chinese ownership or management of these ports allows China to build military capabilities at overseas bases covertly.

Chinese strategic vulnerabilities

China has key strategic vulnerabilities that can be exploited in a long war. Chinese leaders have identified two vulnerabilities of great strategic concern: the “Malacca Dilemma” and internal instability that could threaten the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) rule.15Navya Mudunuri, “The Malacca Dilemma and Chinese Ambitions: Two Sides of a Coin,” Diplomatist, July 7, 2020, https://diplomatist.com/2020/07/07/the-malacca-dilemma-and-chinese-ambitions-two-sides-of-a-coin/. While Chinese officials no longer use the phrase “Malacca Dilemma,” it still captures China’s fundamental vulnerability to a blockade. If exploited, this vulnerability would contribute significantly to China’s economic exhaustion.

Malacca dilemma

China’s greatest geostrategic vulnerability is its isolation from the Pacific and Indian Oceans by the First Island Chain. This makes Chinese seaborne trade highly vulnerable to interdiction. Further, since most of the major exits to the South China and East China Seas are at significant distances from the Chinese mainland, China would have to project its military forces over longer ranges to disrupt any US or allied blockade operations. Even if China can penetrate a blockade of the First Island Chain, it faces additional maritime choke points en route to European and Middle Eastern markets. Most notable are the Strait of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandab Strait.

The Chinese leadership’s concern over the Malacca Dilemma is based on genuine economic vulnerabilities. China’s energy, food, and productive capacity heavily rely on seaborne trade. To reduce its vulnerability to interruption of its seaborne commerce, China has invested significant resources in pipelines and overland rail routes.

China has made serious investments to reduce its vulnerability to blockade operations. It is essential to examine those steps and the reasons they remain vulnerable.

Rail–an effort to overcome the Malacca Dilemma?

China has invested heavily in improving its ability to ship to Europe by rail. According to the China State Railway Group Company, it moved 1,460,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) by rail in 2021.16Ji Siqi, “What is the China-Europe Railway Express, and how much pressure is it under from the Ukraine crisis?” South China Morning Post, March 6, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3169239/what-china-europe-railway-express-and-how-much-pressure-it. This peak throughput occurred prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, which has restricted rail traffic. For comparison, China’s ports handled 262 million TEUs in 2021.17“China Container Port Throughput,” CEIC, last updated December 2021, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/china/container-port-throughput. Thus, rail routes accounted for only 0.6 percent of its global seaborne trade.

Expanding capacity to handle more than a minor fraction of seaborne trade will be extremely difficult. Russian Railways projects that it will be able to transit 4 million containers by 2027. However, its spokesman admits that shortages of container platforms, skilled workers, throughput capacity, and marshaling yards restrict its current operations.18“Russian Railways predicted a four-fold increase in container transit,” ERAI, March 28, 2023, archived at Internet Archive, November 2, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20241102153525/https://index1520.com/en/analytics/rzhd-sprognozirovali-rost-tranzita-konteynerov-v-chetyre-raza/. Kazakh railways, the only other route, do not offer prospects for increased trade. The Kazakh-China border crossings are regularly overwhelmed by traffic. At the beginning of September 2024, fifty-five trains were backed up at the border. To reduce the congestion, Kazakhstan banned further containers until it could clear the backlog.19“The Kazakh-Chinese border remains an obstacle for rail traffic,” RailFreight.com, September 26, 2024, https://www.railfreight.com/beltandroad/2024/09/26/the-kazakh-chinese-border-remains-an-obstacle-for-rail-traffic/. Further complicating any efforts to increase overland transportation throughput is the fact both rail and road connections pass through thousands of miles of the most hostile terrain in the world—mountains, jungles, and deserts. These conditions magnify both the expense of transport and the cost of maintaining rail and road networks. Additionally, most of the rail infrastructure is not operated or maintained by China, but instead by Russia and Kazakhstan. Finally, the very nature of rail lines makes them subject to wartime interdiction.

China has also proposed rail projects to Thailand, Myanmar, and Pakistan, but these projects continue to face delays.20Shan Wu Su, “China’s Rail Diplomacy in Southeast Asia,” Asia-Pacific Journal, September 22, 2024, https://apjjf.org/2024/9/wu. The cargo that will eventually feed these rail connections must come primarily from maritime shipping. Thus, these proposed rail lines will not dramatically reduce China’s dependence on the sea but will only allow it to avoid key choke points created by the First Island Chain. However, even if these lines triple rail throughput, they will still provide less than 2 percent of China’s current seaborne trade. The fact remains that rail simply cannot provide China with a significant substitute for seaborne trade.

This calls into question whether China designed these rail lines not as alternate trade routes but as inland routes to support distant overseas ports and bases. China and Pakistan are planning a rail line to link Kashgar, China, to Gwadar, a Pakistani port city on the Arabian Sea.21Umair Jamal, “China-Pakistan Ties Steam Ahead With Proposed Rail Project,” Diplomat, May 3, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/05/sino-pakistani-ties-steam-ahead-with-proposed-rail-project/. In late 2023, China and Myanmar announced the resumption of work on the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, which will link Kunming, China, to Kyaukpyu and Yangon, Myanmar—both located on the Bay of Bengal.22“China Begins Surveys for Railway on Myanmar’s Indian Ocean,” Irrawaddy, April 18, 2024, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/china-begins-surveys-for-railway-on-myanmars-indian-ocean.html.

Energy

Not surprisingly, China uses a full range of energy sources. At 55.6 percent of the total, coal is by far China’s largest energy source. The next largest source is oil, at 17.7 percent. Then, in descending order, are natural gas (8.4 percent), renewables (8.4 percent), hydro (7.7 percent), and nuclear power (2.3 percent).23C. Textor, “Primary energy consumption in China from 2019 to 2022, by fuel,” Statista, January 24, 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/265612/primary-energy-consumption-in-china-by-fuel-type-in-oil-equivalent/.

China has massive coal production capacity and reserves. Yet, in 2022, it imported 375 million metric tons of coal, or 8 percent of its coal needs.24Avery Chen, “China’s coal imports headed for record year in 2023,” S&P Global, June 20, 2023, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/china-s-coal-imports-headed-for-record-year-in-2023-76185032. The imports, primarily from Indonesia and Australia, consisted of higher-quality coal unavailable in China but needed for certain industrial processes.

Analysis often cites the fact that China imports 72 percent of the oil it consumes as a primary strategic vulnerability.25Ariel Cohen, “China’s Energy Vulnerabilities Drive Xi’s Policies,” Forbes, October 19, 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/arielcohen/2022/10/19/chinas-energy-vulnerabilities-drive-xis-policies/. But too often, analysts do not note that oil represented less than 18 percent of China’s primary energy consumption in 2022. Recognizing a potential vulnerability, China began building a strategic petroleum oil reserve in 2007. Today,

- China’s inventory [is] near 1.3bn barrels, enough to cover 115 days of imports (America holds 800m barrels). On top of this, China has told oil firms to add 60m to stockpiles by the end of March [2025]. Rapidan [Energy] thinks reserves will grow even faster, with China adding as many as 700m barrels by the end of 2025.26Economist, July 23, 2024, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2024/07/23/why-is-xi-jinping-building-secret-commodity-stockpiles.

In the past, China has also delivered oil by rail. With full mobilization, China might be able to import five hundred thousand barrels per day from Russia and Kazakhstan.27Gabriel Collins, “A Maritime Oil Blockade Against China—Tactically Tempting but Strategically Flawed,” Naval War College Review 71, no. 2 (Spring), https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1735&context=nwc-review. However, this would displace other potential traffic. That said, most of China’s liquid energy imports are used in the transportation and petrochemical industries.

Natural gas does not represent a significant vulnerability either. As of spring 2024, China had only about twenty-three days’ natural gas supply in storage. However, in 2022, natural gas imported by sea represented only 2 percent of China’s total energy.28“Why is Xi Jinping building?” The reductions in liquid energy consumption seen during the COVID-19 pandemic indicate the impact that wartime restrictions on civilian movement could have on China’s energy demands.29“China,” U.S Energy Information Administration, updated November 14, 2023, https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/CHN.

Any major conflict between the United States and China would cause significant economic disruption globally, thus strongly reducing the demand for Chinese products. This would further reduce China’s liquid energy requirements and extend the life of its energy reserves. In sum, interruptions of imported liquid energy would strain China’s economy but would not be decisive.

Food

China faces insoluble food security issues. With only 10 percent of the world’s arable land, it must feed 20 percent of the world’s population.30Zongyuan Zoe Liu, “China Increasingly Relies on Imported Food. That’s a Problem,” Council on Foreign Relations, January 25, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/article/china-increasingly-relies-imported-food-thats-problem. In 2014, China’s government reported that 20 percent of its arable land suffered from heavy metal pollution. Compounding these problems is the carbon content of Chinese soil, which is 30 percent lower than the world average. To compensate, Chinese farmers use 33 percent of all fertilizer produced worldwide. This overuse of fertilizer causes acidification and hardens the soil.31Matteo Cavallito, “China launches a new initiative against soil pollution,” Re Soil Foundation, December 1, 2022, https://resoilfoundation.org/en/environment/china-soil-pollution. In addition, over 40 percent of China’s land area is affected by erosion—perhaps the most severe damage in the world.32Claudio O. Delang, “The consequences of soil degradation in China: a review,” GeoScape 12, no. 2 (December 2018): 92–103, DOI:10.2478/geosc-2018-0010.

The net result is that China:

- [I]mports more of these [food] products—including soybeans, corn, wheat, rice, and dairy products—than any other country. Between 2000 and 2020, the country’s food self-sufficiency ratio decreased from 93.6 percent to 65.8 percent. Changing diet patterns have also driven up China’s imports of edible oils, sugar, meat, and processed foods. In 2021, the country’s edible oil import-dependency ratio reached nearly 70 percent…33Liu, “China Increasingly Relies on Imported Food.”

Chinese leaders are acutely aware that food shortages have historically led to instability and have, therefore, stockpiled a year’s worth of wheat and maize.34“Why is Xi Jinping building?” The chart below demonstrates the massive increase in grain purchases since 2010. This trend partly reflects China’s growing wealth and the need to feed more livestock as the Chinese diet increasingly includes meat.35“Could economic indicators give an early warning of a war over Taiwan?” Economist, July 27, 2023, https://www.economist.com/china/2023/07/27/could-economic-indicators-signal-chinas-intent-to-go-to-war.

China also faces severe water shortages, particularly in the north, where much of its agricultural production is concentrated. That region holds just 4 percent of the country’s water. As a result, Chinese agriculture relies heavily on groundwater, but half of its aquifers are too polluted for irrigation. Nationwide, up to 25 percent of river water is also unsuitable for agricultural use.36Henry Storey, “Water scarcity challenges China’s development model,” Interpreter, September 29, 2022, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/water-scarcity-challenges-china-s-development-model. To address its water distribution problem, China is building massive water transportation systems, but it is unlikely to significantly increase grain production in a crisis.

Productive capacity

In 2022, China imported more than $325 million in non-food raw materials per month.37“China Imports of Non-food Raw Materials,” Trading Economics, last updated February 2024, https://tradingeconomics.com/china/imports-of-non-food-raw-materials. This included 70 percent of total global seaborne iron ore imports—about 1.2 billion tons per year.38Clyde Russell, “China’s iron ore imports may hold up despite gloomy economy,” Reuters, August 15, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/chinas-iron-ore-imports-may-hold-up-despite-gloomy-economy-2023-08-15. Chinese domestic production that year was 380 million tons, covering only 24 percent of its annual needs.39C. Textor, “Production of iron ore in China from 2010 to 2022,” Statista, February 9, 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/307473/china-iron-ore-production/. While China is the world’s fourth-largest producer of copper,40GlobalData, “Copper production in China and major projects,” Mining Technology, updated August 23, 2024, June 28, 2023, https://www.mining-technology.com/data-insights/copper-in-china/?cf-view. it is also the world’s largest importer, accounting for 58 percent of global copper ore imports.41“Copper ores and concentrates | Imports and Exports | 2022,” TrendEconomy, January 28, 2024, https://trendeconomy.com/data/commodity_h2/2603.

Although China has the world’s largest shipbuilding industry, accounting for 48.4 percent of the global shipbuilding tonnage, the industry is heavily dependent on imports.42Wenyi Zhang, “Ship tonnage in orderbook of Chinese shipbuilding industry 2014-2021,” Statista, December 20, 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1064122/china-tonnage-in-orderbook-of-shipbuilding-industry/. If US allies can maintain sea control in a prolonged conflict, China will struggle to obtain the raw materials needed to sustain its economy and war production. Nations that have been blockaded in the past have made significant cuts to civilian production to support their war efforts. Doing so allowed the Confederacy, Germany, and Japan to extend their military efforts for years; however, in the end, blockades caused substantial reductions in their industrial outputs.

Trade

China has made significant efforts to shift from an export-based economy to a domestic demand-driven one. It has reduced its dependence on trade from over 60 percent of its GDP in 2006 to 38 percent in 2022.43“Trade (% of GDP) – China,” World Bank Group, accessed October 30, 2024, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.TRD.GNFS.ZS?locations=CN. However, 90 percent of this trade remains seaborne.44Kardon and Leutert, “Pier Competitor.” To illustrate the potential impact of interruptions to seaborne trade, the Great Depression reduced the US GDP by 29 percent from 1929 to 1933.45David Wheelock, “How Bad Was the Great Depression? Gauging the Economic Impact,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, video, July 11, 2013, https://www.stlouisfed.org/the-great-depression/curriculum/economic-episodes-in-american-history-part-3. A RAND study noted that China’s economy may contract by 25 to 35 percent in a prolonged war.46David C. Gompert, Astrid Stuth Cevallos, and Cristina L. Garafola, War with China: Thinking Through the Unthinkable, RAND, 2016, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1100/RR1140/RAND_RR1140.pdf. A contraction of this magnitude would not only severely hinder China’s military-industrial production but could also contribute to internal instability—Chinese President Xi Jinping’s primary concern.

Internal instability

The CCP’s leadership views internal instability as the primary threat to its continued rule. Since the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, China has dramatically increased its focus on internal security. It reorganized the People’s Armed Police, and by 2017, its internal security budget was 118 percent of its national defense budget.

China no longer publishes its internal security budget. However, its massive efforts to suppress Uighurs in Xinjiang, its coordinated nationwide surveillance of nearly every aspect of its citizens’ lives, and its extensive control over information all underscore the CCP leadership’s belief that internal instability is a major strategic threat.

Joel Wuthnow, a senior research fellow at the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs within the Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University, noted:

- The ultimate irony of the regime presiding over the ‘people’s republic’ is that its greatest fear is that one day, it will have to confront the wrath of the Chinese people directly. Worrying about internal challenges is ‘what keeps Chinese leaders awake at night.’47Joel Wuthnow, System Overload: Can China’s Military Be Distracted in a War over Taiwan? in China Strategic Perspectives, no. 15, ed. Phillip C. Saunders (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, June 2020) https://inss.ndu.edu/Media/News/Article/2232448/system-overload-can-chinas-military-be-distracted-in-a-war-over-taiwan/.

The People’s Liberation Army

The Office of the US Secretary of Defense provides an unclassified Annual Report to Congress, and the Congressional Research Service regularly produces reports on the PLA. This article does not attempt to duplicate these efforts. Instead, it focuses on how China can use existing and projected PLA capabilities to disrupt international shipping during a conflict with the United States.

Chinese potential use of overseas ports and bases

Security concerns regarding Chinese ownership of overseas ports fall into three general categories. First is the massive amount of intelligence China collects. Second is the potential to use this intelligence and control of key ports and piers to disrupt US shipments in times of war. Finally, there is the possibility that China could leverage its control of these ports to pre-position weapons, ammunition, and equipment—either to replenish its warships and armed merchants or to rapidly establish A2/AD nodes near major maritime choke points. In short, it can disrupt global maritime trade.

Simply by running international ports, China acquires and collects enormous amounts of information on maritime trade flows. It also developed its National Transportation and Logistics Public Information Platform, known as LOGINK, a software system designed to manage global shipping. As John Konrad writes:

- Initially marketed outside of China in 2010, LOGINK has since expanded its footprint, securing cooperation agreements with at least 24 global ports. Its capacity to amass sensitive business and foreign government data, such as corporate registries, vessel details, and cargo data, has raised significant security concerns.

Quoting a U.S.-China Economic and Security Commission report,48USCC Staff, “LOGILINK: Risks from China’s Promotion of a Global Logistics Management Platform,” US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, September 20, 2022, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2022-09/LOGINK-Risks_from_Chinas_Promotion_of_a_Global_Logistics_Management_Platform.pdf. Konrad adds:

- COSCO [China COSCO Shipping Corporation] currently operates terminals at Long Beach, Los Angeles, and Seattle, potentially granting LOGINK a window into vessel, container, and other data at those ports.49John Konrad, “U.S. Sounds Alarm on China’s Leading Ship Logistics Software LOGINK,” gCaptain, August 24, 2023, https://gcaptain.com/u-s-sounds-alarm-on-chinas-ship-logistics-software-logink/.

This information could provide China with global intelligence on the movement of US forces, materiel, and equipment during a crisis. China could use this intelligence to disrupt the movement of US and allied materiel in the event of conflict. It did so in 2016 when it seized eight Singaporean Terrex infantry carriers as they transited the port of Hong Kong while returning from exercises in Taiwan.50Euan Graham, “China pressures Singapore with seizure of military hardware,” Lowy Institute, December 6, 2016, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/china-pressures-singapore-seizure-military-hardware.

Due to the United States’ heavy reliance on commercial shipping, some of this maritime traffic will pass through Chinese-controlled ports. Much more will be visible in LOGINK. Both possibilities create opportunities to corrupt logistics databases and even reroute critical items. There is a also concern that the widespread use of Chinese-produced cranes could allow China to disrupt trade in ports it neither owns nor operates.51Isaac B. Kardon, “Washington Tackles a New National Security Threat: Chinese-Made Cranes,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 28, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/2024/02/28/washington-tackles-new-national-security-threat-chinese-made-cranes-pub-91843.

The third threat is the potential to use these ports—or even individual piers—to pre-position equipment that could transform each into an intelligence collection node, a rearming point to replenish containerized missiles on Chinese warships or merchant ships, an A2/AD node to disrupt international shipping, or any combination of the three.

In the least aggressive approach, China could employ these ports for intelligence gathering and soft-kill operations. PLA personnel could use pre-positioned electronic warfare (EW) and cyber equipment for offensive operations or as a basis for intelligence collection beyond what is obtained through LOGINK. The PLA could also deploy long-endurance drones or balloons as platforms for multi-spectral, synthetic-aperture radar (SAR), radar, and EW sensors. While permitting the use of these ports in a conflict could legally render the host nation a belligerent, it is not difficult to envision host nations turning a blind eye to drones collecting “weather” or “environmental” information. Nor would it be surprising if the host nations simply pretended not to know about any Chinese intelligence personnel conducting cyber or EW operations from their soil. Every port could become an intelligence collection node along key maritime routes.

The next step would be to use these ports to replenish containerized weapons deployed on Chinese-owned commercial ships. Since these vessels would routinely load and unload containers at the piers, the activity would not appear unusual and would be subtle enough for the host nation to ignore. The PLA has displayed these systems at trade shows since 2022.52“#36 – China’s Container-launched Cruise Missiles,” Vermilion China, February 23, 2023, https://www.vermilionchina.com/p/36-chinas-container-launched-cruise. Its systems appear very similar to the Club-K family of containerized missiles that Russia has offered for sale since 2010.53Michael Stott, “Deadly new Russian weapon hides in shipping container,” Reuters, April 26, 2010, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/deadly-new-russian-weapon-hides-in-shipping-container-idUSTRE63P2XB/#:~:text=%22Nobody’s%20ever%20done%20that%20before,wrong%20hands%2C%22%20he%20said. In recent years, Israel, Iran, the United States, and the Netherlands have also tested containerized missiles. These ports could also be used to rearm People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) ships.

The final—and least likely, but most aggressive—course of action would be to use these ports to establish effective counter-intervention nodes. These nodes would require effective command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities, as well as anti-ship defenses, anti-air defenses, and EW units. Depending on the location and the potential for US or allied response, they may also require limited ground defenses to protect against attempts to destroy the Chinese weapons systems stationed there.

Prior to a conflict, China could pre-position weapons, ammunition, and equipment without the host nations’ knowledge. The PLA could build significant stockpiles of command and control (C2), EW, cyber, anti-air, anti-ship, and anti-armor equipment and munitions by transporting them in commercial containers via Chinese shipping companies. Upon arrival, they could be unloaded and stored in warehouses or container lots controlled by Chinese companies. Similar to US pre-positioning programs, China would only need to fly in personnel and limited equipment to rapidly establish fully equipped intelligence centers or combat formations. If flights were impossible, smugglers have demonstrated that large numbers of people can be moved in containers on merchant ships.

Weapons and vehicles too large to be containerized could be shipped aboard one of China’s numerous commercial vessels, which could be specifically modified to carry military equipment. Personnel could be flown in or travel with their equipment on these ships.

Given that Chinese forces would likely be focused on air and sea interdiction, these forces would not require large, personnel-intensive infantry, logistics, and aircraft maintenance units. Thus, deployment and employment could be executed rapidly in peacetime. These factors could provide China with robust forces capable of shutting down shipping at maritime choke points across the South China Sea, Indian Ocean, Middle East, and potentially parts of the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea.

If these ports are configured to be effective A2/AD nodes, they could be used in two ways. First, China could assert that these forces would not be used unless the United States or its allies attempted to cut off maritime trade to China. Alternatively, China could threaten the maritime trade of individual nations that choose to support the United States. If these threats fail and the United States imposed a distant naval blockade, China could use these nodes to cause massive disruption to global trade.

Meia Nouwens of the International Institute for Strategic Studies says that Chinese leaders understand that an Indo-Pacific war will not be “a short, quick, swift victory after a surprise attack, but [acknowledge] that potential conflict might be protracted, and a war of attrition.”54Rhyannon Bartlett-Imadegawa, “China preparing for ‘protracted’ war, says think tank,” Nikkei Asia, February 14, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Defense/China-preparing-for-protracted-war-says-think-tank. China is aware that a prolonged war will be won or lost on economic and industrial resilience. Cutting global trade would significantly and negatively impact US economic and industrial capacity. Chinese leaders are likely aware this step would alienate the international community and perhaps convince some nations to align with the United States. While this is a significant risk, the CCP would have already taken an existential risk (for the party, not the country) by choosing conventional warfare with the United States.

By the same standards, US efforts to disrupt these sites risk alienating host nations. This will be particularly true if the Chinese are merely conducting intelligence-gathering operations without kinetic actions or interference with the host nation’s trade.

US intelligence has tracked China’s development of mainland counter-intervention (A2/AD) capabilities for over a decade. China has spent decades developing the systems and weapons necessary to create overlapping, integrated observation and fire zones at ever-greater distances from its mainland. Today, China is emphasizing the integration of air, land, sea, space, cyber, EW, and information capabilities to maximize the effectiveness of its counter-intervention capability. It is also increasing its inventory of mobile systems and showcasing containerized systems at international trade shows.55“#36 – China’s Container-launched.”

Combined with its ownership and control of overseas ports, this capability gives China the potential to create “pop-up” counter-intervention nodes near critical maritime choke points. The capabilities discussed below can all be deployed to overseas ports using standard shipping containers or roll-on/roll-off (RO/RO) shipping. With the C2 systems, weapons, and munitions pre-positioned in these ports, personnel can be flown in and establish effective units in a matter of days.

Systems China could covertly deploy to overseas ports/bases

Command-and-control systems

The critical asset that will enable China to integrate its wide-ranging locations and coordinate the employment of the systems is an effective global C2 system. The theater commands the PLA established in 2016 are still working toward achieving full joint capability, and none have been designated to conduct the type of operations described in this paper. Therefore, how China would command such an operation remains an open question. To date, the naval headquarters has commanded the PLAN deployments to the Middle East. However, given the PLA’s determined efforts to master joint operations, China is likely developing some form of joint command for overseas deployments.56Phillip C. Saunders, Beyond Borders: PLA Command and Control of Overseas Operations, Strategic Forum no. 306 (July 2020), Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University, https://inss.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratforum/SF-306.pdf.

The PLA will require a robust C2 with integrated global communications; long-range intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); EW; and cyber defense. The technical components necessary for such a command structure either already exist or are currently under development.

China is a near-peer or peer in military remote sensing, creating new and enhanced dilemmas for US and allied military planners: The United States will face a PLA with improved intelligence, tracking, and targeting capabilities, complicating efforts to deter or carry out military operations within the second island chain in the Indo-Pacific.57Tate Nurkin, et.al., China’s Remote Sensing, OTH Intelligence Group LLC, December 2024, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2024-12/Chinas_Remote_Sensing.pdf.

China has plans to launch twenty-six thousand communication satellites into low-earth orbit (LEO) to provide Starlink-like global broadband capabilities.58Shunsuke Tabeta, “China to launch 26,000 satellites, vying with U.S. for space power,” Nikkei Asia, January 10, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Aerospace-Defense-Industries/China-to-launch-26-000-satellites-vying-with-U.S.-for-space-power. To augment its existing BeiDou Global Navigation Satellite System and ChinaSat communications satellites, China launched Weixing Hulianwan Gaogui-01, its first “high orbit internet satellite.”59Andrew Jones, “China launches first high orbit internet satellite,” Space News, February 29, 2024, https://spacenews.com/china-launches-first-high-orbit-internet-satellite/. BeiDou, ChinaSat, and Gaogui-01 operate in geosynchronous orbit (GEO).

In December 2023, China launched Yaogan-41, a remote-sensing satellite, into GEO. It added to China’s constellation of 144 Yaogan satellites, providing “an unprecedented ability to identify and track car-sized objects throughout the entire Indo-Pacific.”60Clayton Swope, “No Place to Hide: A Look into China’s Geosynchronous Surveillance Capabilities,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 19, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/no-place-hide-look-chinas-geosynchronous-surveillance-capabilities. As a GEO orbiting satellite, it provides a constant observation of the same region, unlike LEO satellites, which make intermittent passes. China also operates three Gaofen electro-optical equipped satellites in GEO, with resolutions as precise as 15 meters. In 2023, China launched the world’s only SAR satellite in GEO orbit, enabling the satellite to see through clouds and in darkness.61Swope, “No Place to Hide.”

These systems will provide a local commander access to Chinese satellite intelligence and can be augmented by long-range drones and balloons. China could deploy its vertically launched Sunflower drones, which have a 1,200-mile range and an 88-pound payload, allowing them to carry various sensors and communications systems. China has already demonstrated its ability to use high-altitude balloons as collection platforms.

The Russo-Ukrainian War has highlighted the importance of effective EW and electronic intelligence systems. It has also demonstrated the growing effectiveness of relatively small EW systems that could easily fit in a TEU. Even before the war in Ukraine, China took steps to strengthen its EW capabilities. In 2015, China established the Strategic Support Force (SSF) to develop and coordinate space, cyber, electronic, and psychological warfare capabilities. In April 2024, China announced that it had split the SSF into three branches: the Information Support Force, Network Space Force, and Military Aerospace Support Force.62Dean Cheng, “Why Xi created a new Information Support Force, and why now,” Breaking Defense, April 29, 2024, https://breakingdefense.com/2024/04/why-xi-created-a-new-information-support-force-and-why-now/. While analysts still do not fully understand how responsibilities will be divided among these new forces, it is clear that China remains committed to enhancing its capabilities in these domains.

A key advantage of these C2 capabilities is that the equipment—and even personnel—can be covertly transported and deployed.

Anti-ship systems

Anti-ship systems, ranging from low-cost weapons to high-end cruise missiles, will be central to any Chinese attempt to use overseas bases and ports to disrupt trade.

Sea mines

Sea mines are among the cheapest and most effective anti-ship systems. Given the widely recognized deficiencies in the US Navy’s modern counter-mine warfare, China is well aware of their effectiveness.63Jan Tegler, “Navy Mine Warfare Teeters Between Present, Future,” National Defense, January 17, 2023, https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2023/1/17/navy-mine-warfare-teeters-between-present-future. In 2023, the China Maritime Studies Institute at the US Naval War College’s Center for Naval Warfare Studies noted:

- China has begun to prioritize mine warfare and the PLAN has a comprehensive, sophisticated sea mine program …. [A] large, diverse inventory of sea mines including advanced variants and trains extensively in minelaying.64Quick Look Report: Chinese Undersea Warfare: Development, Capabilities, Trends, China Maritime Studies Institute, Center for Naval Warfare Studies, US Naval War College, May 2023, https://www.andrewerickson.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Naval-War-College_China-Maritime-Studies-Institute_CHINESE-UNDERSEA-WARFARE_CONFERENCE-SUMMARY_20230505.pdf.

While many studies have focused on China’s use of mines to isolate Taiwan, sea mines are easy to transport and can be covertly deployed by almost any ship. China has designated mine-laying a mission for commercial vessels in its naval reserve. Given the challenges of mine sweeping and the limited capabilities among Western nations, even a small number of mines in maritime choke points could cause long-term trade disruptions. Following the Gulf War, it took Australians almost five months to search “two square kilometres and [deal] with [just] 60 mines.”65Elizabeth White, “Sea mines are cheap and low-tech, but they could stop world trade in its tracks,” Strategist, March 6, 2020, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/sea-mines-are-cheap-and-low-tech-but-they-could-stop-world-trade-in-its-tracks/. Those mines employed decades-old technology. The modern mines in China’s arsenal will be exponentially more difficult to neutralize. Even if an area can be cleared, it can easily be reseeded by false-flagged commercial or fishing vessels during routine passages through maritime choke points.

Uncrewed aerial vehicles

In Ukraine, UAVs have destroyed targets ranging from individual soldiers to armored vehicles to major industrial facilities and even warships—at distances of up to 1,800 kilometers.66Leo Chiu, “Ukraine’s Drone Strike Radius Now 1,800 km – What’s on Kyiv’s Target List?” Kyiv Post, September 9, 2024, https://www.kyivpost.com/post/38716.

China is well known for manufacturing most of the world’s quadcopters, but it also produces a family of military drones. China’s FH-901, for example, bears a remarkable resemblance to the US Switchblade.67“Airshow China 2022: CASC unveils FH-97A loyal wingman autonomous drone,” Global Defense News, November 9, 2022, https://armyrecognition.com/news/aerospace-news/2022/airshow-china-2022-casc-unveils-fh-97a-loyal-wingman-autonomous-drone. These munitions have limited range but carry more powerful warheads than the hobby quadcopters widely used in Ukraine. They would be particularly effective in very restricted waterways such as the Bab al-Mandab Strait.

China’s Sunflower 200 represents a significant leap in capability. Online videos show China developing a launching system similar to Iran’s commercial truck-mounted launcher.68Daria Dmytriieva, “China unveiled a new kamikaze drone: Improved copy of Iranian Shahed,” RBC-Ukraine, August 17, 2023, https://newsukraine.rbc.ua/news/china-unveiled-a-new-kamikaze-drone-improved-1692269951.html. These relatively inexpensive, mass-produced drones pose a clear threat to merchant shipping as well as commercial and military base facilities.

China is also developing high-performance, long-range drones. The Feihong FH-97A is “capable of ‘all-day, all-weather’ operations in support of reconnaissance and attack missions.”69Ritu Sharma, “‘Catching-Up’ With China, US Pushes Its 6th-Gen Combat Drone Program; Set To Award Contract For 1st Batch Of CCA,” Eurasian Times, February 14, 2024, https://www.eurasiantimes.com/us-accelerates-combat-drone-program-to-catch/. The FH-97A bears a striking resemblance to the US XQ-58A Valkyrie, which has a range of 3,500 miles, can carry up to 1,000 pounds, and cruises at Mach 0.7.70Colin Demarest, “AI-enabled Valkyrie drone teases future of US Air Force fleet,” Defense News, January 18, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/unmanned/uas/2024/01/18/ai-enabled-valkyrie-drone-teases-future-of-us-air-force-fleet/. If the FH-97A’s capabilities match those of the Valkyrie, it could provide a globally deployable long-range strike. Given China’s investment in artificial intelligence, it is likely that these aircraft will soon be autonomous—if they are not already.

If concealed in standard shipping containers, these weapons could be quickly shipped into any port controlled by a Chinese company. The FH-97’s estimated 3,000-mile range means it could strike shipping throughout the Indian Ocean, most of the Atlantic, and much of the Pacific from a Chinese-controlled port. Even more concerning, these systems could target fixed air bases or ports supporting US operations.

Uncrewed surface vessels/uncrewed underwater vessels

Over the last two years, Ukraine’s USVs have sunk or damaged Russian naval vessels both in the open sea and in port.71Claudia Chiappa, “Russia to build naval base in breakaway Georgia region,” Politico, October 5, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/vladimir-putin-russia-black-sea-abkhazia-plans-to-build-naval-base-in-georgias-breakaway-region-as-it-pulls-vessels-from-sevastopol-base/. The China Maritime Studies Institute at the US Naval War College’s Center for Naval Warfare Studies recently reported:

- “The PLAN either has or is poised to integrate USVs and UUVs into its operational force. It seeks to build larger USVs and UUVs to carry more capable payloads and perform a broader range of operations. Combat USVs are currently undergoing sea trials and AI integration.”72Quick Look Report.

Potential employment of uncrewed systems

Since most of these systems are small enough to fit in a standard TEU, they are an obvious choice for supporting sea denial operations from overseas ports. Of particular concern is the potential for these drones to hunt autonomously. The map below illustrates the vast areas these drones could cover when launched from Chinese-owned ports. Of course, range rings do not prevent opposing forces from maneuvering within them, but the imminent threat of damage may lead commercial shipping to avoid the area. Illustrative of this point, major shipping firms have largely abandoned the use of the Suez Canal due to the threat of drones and missiles from the Houthis in Yemen.

Multiple rocket launchers

China fields battalions of PCH191 multiple rocket launchers equipped with satellite or inertial navigation systems, capable of firing the TL-7B missile. This missile can conduct sea-skimming flights to deliver a 700-pound warhead at a range of 120 miles.73Joshua Arostegui, China Maritime Report No. 32: The PCH191 Modular Long-Range Rocket Launcher: Reshaping the PLA Army’s Role in a Cross-Strait Campaign, China Maritime Studies Institute, US Naval War College, November 3, 2023, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1031&context=cmsi-maritime-reports. While most multiple rocket launchers are too large to fit in a shipping container, the rocket pods themselves fit easily in standard forty-foot-equivalent-unit containers. Over time, China could discreetly transport and stockpile rocket ammunition in Chinese-owned containers within the port. The launchers could then be loaded onto various Chinese-owned RO/RO ships and offloaded just before a campaign begins. The primary disadvantage is that their function would be difficult to conceal if the launchers were observed during loading or unloading.

Cruise missiles

Cruise missiles are proven ship-killers, and several of these systems have capabilities that would enable Chinese-held ports to provide mutual support. China currently fields six major anti-ship cruise missile systems (ASCMs): YJ-12, YJ-18, YJ-21, YJ-62, YJ-83, and CJ-100. These systems carry ship-killing warheads with ranges ranging from 130 to 1,000 miles. All can be embarked on modified RO/RO vessels, while the YJ-18 and YJ-83 can be containerized.

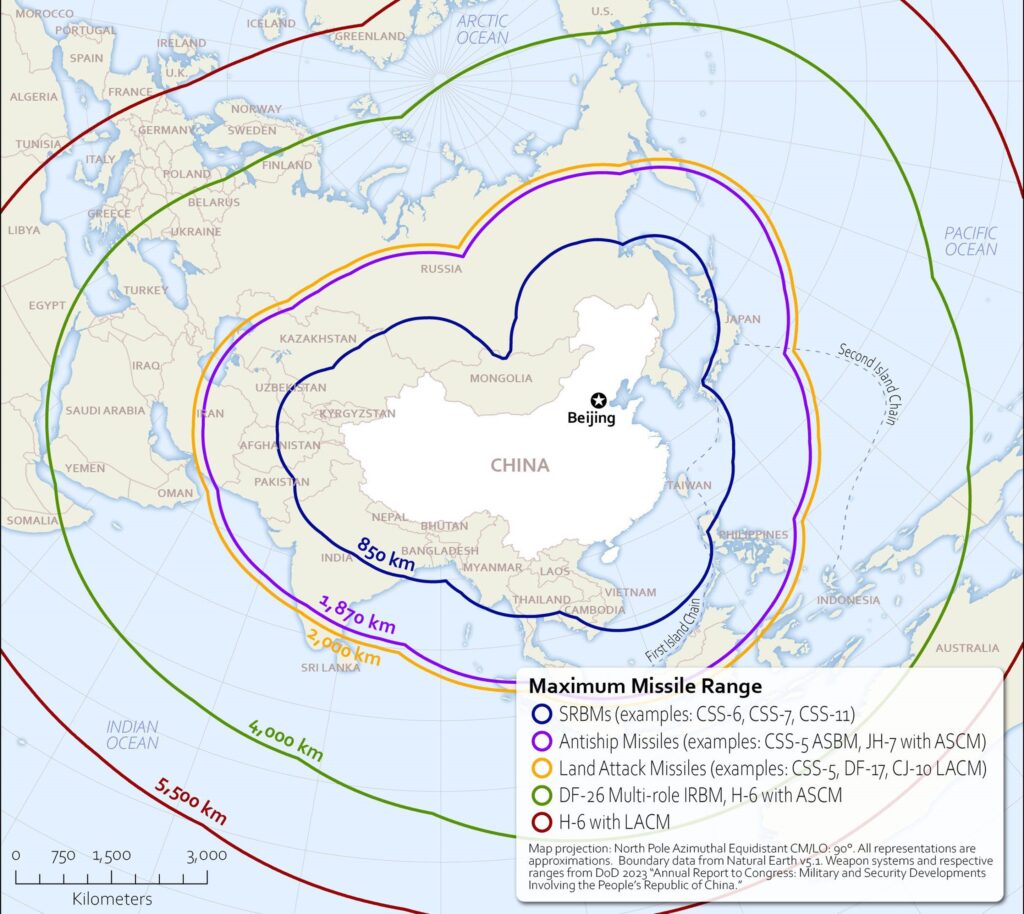

Maximum range of Chinese missiles

Anti-ship ballistic missiles

The DF-21D is a road-mobile ballistic missile system with a range of 1,500 kilometers. From mainland China, it can reach most of the South China Sea and significant parts of the Bay of Bengal. The longer-range DF-26 (4,000 kilometers) can cover the entire South China Sea, much of the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the eastern one-third of the Mediterranean Sea.74“Missiles of China,” Missile Threat, CSIS Missile Defense Project, Center for Strategic and International Studies, updated April 12, 2021, https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/china/. The DF-27 has a range between 5,000 and 8,000 kilometers, it is also road-mobile, carries a hypersonic glide vehicle, and, like the DF-26, comes in land-attack and anti-ship variants.75Zuzanna Gwadera, “Intelligence leak reveals China’s successful test of a new hypersonic missile,” International Institute of Strategic Studies, May 18, 2023, https://www.iiss.org/en/online-analysis/online-analysis/2023/05/intelligence-leak-reveals-chinas-successful-test-of-a-new-hypersonic-missile/. It can target the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and most of the Mediterranean Sea. In short, the PLA can leverage its China-based ballistic missiles to reinforce sea denial operations across most of Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean Sea.

Ground-based anti-air systems

This past year, the challenge of locating and destroying mobile missile systems from the air has been widely demonstrated in both Ukraine and Yemen. This suggests that an effective counter-intervention system composed of mobile missile systems can operate without air defense.76Maximillian K. Bremer and Kelly A. Grieco, “Air denial: The dangerous illusion of decisive air superiority,” Atlantic Council, August 30, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/content-series/airpower-after-ukraine/air-denial-the-dangerous-illusion-of-decisive-air-superiority/. However, the inclusion of mobile air defense systems would significantly complicate US or allied efforts to regain control of the ports. Unfortunately, China has developed a family of air defense systems that can be easily transported via RO/RO ships or shipped in containers.

In 2022, PLA air defense units focused on enhancing their tactical air defense against low- and slow-moving threats like UAS and loitering munitions to meet evolving air defense requirements.77Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023, Annual Report to Congress, US Department of Defense, October 19, 2023, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF. Although these systems are primarily designed to counter UAVs, Ukrainian forces have achieved remarkable success using them to destroy Russian helicopters and jets. Larger Ukrainian air defense systems have forced Russian aviation to operate at lower altitudes, bringing with them the engagement range of these lighter systems.

While the anti-UAS systems will be easiest to place in overseas ports, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force also operates a large force of medium and advanced long-range SAM systems. These include Russian-sourced SA-20 (S-300) and SA-21 (S-400) batteries.78Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments, 64. It also fields the domestically produced HQ-9 and HQ-22. The HQ-9 has a range of 120 miles and a maximum altitude of 30,000 meters. Designed to target aircraft, it is typically deployed as a battalion, though even a single battery includes eight transporter erector launchers.79US Army, “HQ-9 (Hong Qi 9) Chinese 8×8 Long-Range Air Defense Missile System,” Operational Data Integration Network (ODIN), accessed October 30, 2024, https://odin.tradoc.army.mil/WEG/Asset/HQ-9. The HQ-22 has a range of 110 miles and a maximum altitude of 27,000 meters. Often compared to the US Patriot system, it can engage cruise missiles, short-range ballistic missiles, aircraft, and drones.80“HQ-22 / FK-3 – Surface-to-Air Missile,” Global Security, accessed X, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/china/hq-22.htm.

These larger systems would require a RO/RO or ferry for deployment. Once operational, they would create an obvious signature but would significantly expand the air defense envelope for hastily established anti-access sites in Chinese-controlled ports. In short, China could rapidly establish an integrated air defense system by unloading large vehicles from Chinese-owned RO/ROs or ferries and integrating them with smaller vehicles and missile stores that had been pre-positioned in the designated port.

Surface warships

China, which already operates the world’s largest navy, plans to continue expanding both the size and capabilities of its surface fleet. By 2035, China will likely be more confident in deploying naval task forces much farther afield. Given its rapid progress in carrier aviation, China will likely possess the capability to launch limited carrier-based aviation in support of surface forces.

The United States must also consider the impact of China placing containerized FH-97A high-performance UAVs—or their successors—on a wide variety of warships and even merchant ships. These UAVs could provide limited air support that outranges projected US naval aircraft. Of particular concern is the potential to arm massive numbers of ships. China currently possesses 3,600 long-range fishing ships and 5,500 large merchant vessels.81“China’s deep-water fishing fleet is the world’s most rapacious,” Economist, December 8, 2022, https://www.economist.com/international/2022/12/08/chinas-deep-water-fishing-fleet-is-the-worlds-most-rapacious; Xioashan Xue, “As China Expands Its Fleets, US Analysts Call for Catch-up Efforts,” Voice of America, September 13, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/as-china-expands-its-fleets-us-analysts-call-for-catch-up-efforts-/6746352.html. With the addition of containerized weapons, C2 suites, and ISR systems, these ships have the potential to sink most merchant vessels and engage many warships. Furthermore, surface ships could both be reinforced and reinforced by any counter-intervention umbrellas provided by Chinese overseas ports and bases.

Transportation

Chinese firms control either entire ports or individual piers in dozens of locations globally.82Kardon and Leutert, “Pier Competitor.” These ports handle tens of thousands of containers daily. Even if the host nation attempted to monitor the contents, it would be virtually impossible—especially since many ports rely on Chinese information systems to track cargo. Thus, China could covertly deliver and store large numbers of containerized C2 systems, weapons, munitions, and supplies without the knowledge of the United States, its allies, or the host nation.

In 2022, China employed thirty RO/ROs in large-scale sealift exercises and further increased production rates, ordering an additional seventy-six for Chinese companies.83Matthew P. Funaiole et al., “China Accelerates Construction of ‘Ro-Ro’ Vessels, with Potential Military Implications,” China Power, Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 11, 2023, https://chinapower.csis.org/analysis/china-construct-ro-ro-vessels-military-implications/. These ships are primarily used to export Chinese cars globally, making their presence a routine part of international shipping.

While a large RO/RO ferry or vehicle carrier could transport more vehicles or troops, a single armored unit—consisting of approximately one hundred and fifty vehicles and one thousand personnel—is a reasonable estimate of what these civilian ships would likely carry in practice.84J. Michael Dahm, China Maritime Report No. 25: More Chinese Ferry Tales: China’s Use of Civilian Shipping in Military Activities, 2021-2022, China Maritime Studies Institute, US Naval War College, January 2023, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1024&context=cmsi-maritime-reports. If a host nation is friendly to China, the PLA could also use its growing inventory of amphibious shipping, long-range military aircraft, and commercial planes to rapidly position its forces.

Potential force for the overseas mission

The PLA possesses all the necessary equipment to exploit its overseas bases and ports. But which Chinese unit could execute such a mission? In October 2021, the China Maritime Studies Institute at the US Naval War College reported:

- Since 2017, the PLAN Marine Corps increased from two to eight brigades – six Marine Brigades, one Maritime Aviation Brigade, and one Special Operations Brigade. The Special Operations Brigade are fashioning themselves after US Navy SEALs.85John Chen and Joel Wuthnow, China Maritime Report No. 18:Chinese Special Operations in a Large-Scale Island Landing, China Maritime Studies Institute, US Naval War College, January 2022, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=cmsi-maritime-reports.

In a January 2024 article, Task & Purpose paraphrased Timothy Heath, a senior international defense researcher at the RAND Corporation, as saying:

- Chinese leaders have said they plan to [further] expand the size of the People’s Liberation Army Navy Marine Corps because they anticipate facing a higher demand for ground forces that can carry out a wide range of missions abroad.86Jeff Schogol, “China is expanding its marine corps, but how capable is it?” Task & Purpose, January 25, 2024, https://taskandpurpose.com/news/china-marine-corps/.

Since the People’s Liberation Army Navy Marine Corps already maintains a battalion-sized force in Djibouti, it is well-positioned to adapt to the fundamentally new mission of establishing covert forces at overseas stations.

Missions of US forces

The potential for China to employ its overseas ports and facilities in a significant conflict presents a serious challenge for US forces. Yet, the challenge lies well within the US Navy’s traditional missions. The 2020 Naval Doctrine Publication 1: Naval Warfare features this quote from Admiral Raymond A. Spruance as a clear statement that the most critical wartime mission for the navy/Marine Corps team is sea control:

- I can see plenty of changes in weapons, methods, and procedures in naval warfare brought about by technical developments, but I can see no change in the future role of our Navy from what it has been for ages past for the Navy of a dominant sea power to gain and exercise the control of the sea… 87Naval Doctrine Publication 1: Naval Warfare (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, April 2020), https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/NDP1_April2020.pdf.

In a long war with China, a foundational mission of US naval forces will be to reestablish and maintain sea control to sustain allied wartime production while severely restricting China’s access to the raw materials essential to its wartime economy.

The emergence of persistent surveillance technologies, along with long-range, mobile, land-based anti-ship missiles, rockets, and drones means that land-based systems can, at times, deny China access to key maritime choke points.

Unfortunately, the PLA arrived at this conclusion much earlier than the United States and has systematically developed a land-based A2/AD capability with deep magazines and redundant coverage extending to increasing ranges from the shore. The Chinese have worked hard to ensure these systems are mobile and, therefore, much more difficult to defeat. While China’s focus to date has been on protecting the Chinese mainland and its near seas, the growing global trend of containerizing effective anti-air, anti-ship, and long-range strike weapons creates new options for the global deployment and employment of these systems.

Pre-conflict, the Joint Force cannot prevent China from leveraging its overseas ports and control of shipping data to disrupt the movement of allied material or to conceal its own material shipments.

Upon the commencement of hostilities, the Joint Force will require an operational approach suited to a war of exhaustion. National command authority will need to establish priorities among competing global demands. While it is impossible to predict how senior officials will prioritize, the Joint Force must be prepared to execute the following tasks in support of sea control:

- Locate and neutralize Chinese efforts to interrupt global trade.

- Establish effective blockades to severely degrade Chinese international trade.

Fortunately, these two missions will draw on different elements of the Joint Force. Unfortunately, the current US Navy thirty-year shipbuilding plan suggests the fleet will be too small to execute a worldwide campaign against Chinese forces and facilities. The US Navy’s combat forces will be insufficient to confront the world’s largest navy and maintain global sea control. To succeed, they will require support from elements of the Joint Force that are not fully engaged. Most analysts predict that the opening campaigns of a US-China conflict will be primarily air and sea battles. If this holds true, the US Army and US Marine Corps will likely not be fully committed.

Potential roles for land-based forces in establishing global sea control

Locate and neutralize Chinese efforts to disrupt military logistics and global trade.

Given the enormous distances involved and the reliance of the United States and its allies on maritime logistics, the first mission must neutralize Chinese efforts to disrupt military logistics. As part of this effort, major fleet and air combat elements must focus on preventing the PLAN from breaking out of the First Island Chain. If granted permission to operate ashore, the Marine Littoral Regiments and Army Multi-Domain Task Forces can provide direct support to this mission. If not, these units have the potential to operate from amphibious or merchant ships. Both services have demonstrated the ability to launch anti-ship cruise missiles from containers, and both could provide helicopter-borne boarding teams to seize ships at sea.

While containing the PLAN is the priority mission, neutralizing Chinese efforts to disrupt trade will also require removing Chinese forces from ports and bases overseas. If equipped as described above, these ports and bases would be capable of interdicting shipping at key maritime choke points. Eliminating this threat will require significant, capable combat forces. However, until these Chinese forces can be reduced, the United States and its allies could establish alternative routes that bypass the South and East China Seas, allowing shipping to reach key allied states such as Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines. These alternative routes would enable US and allied forces to focus first on clearing the key choke points in the Middle East.

A primary challenge to US and allied forces will be determining the strength and disposition of PLA forces in targeted locations. Each plan of action will require a unique approach based on the PLA forces in place, their activities, the host nation’s stance toward both Chinese and US actions, and the availability of joint or combined forces. The same tactics currently planned for degrading China’s mainland A2/AD network will apply to mini A2/AD locations but will require modification based on these conditions.

Given the extended range of Chinese aerial drones, basing aircraft such as the F-35 within range of the weapons systems deployed to Chinese ports would pose a major risk of destruction on the ground or aboard a ship. This risk is particularly high if the base or port has stockpiles of Sunflower drones. The additional presence of FH-97A drones would dramatically extend the range of the threat and pose a significant danger to any aerial tankers used to extend the range of US aircraft.

While US long-range bombers are an obvious first choice to destroy identified targets in these ports, there is a high probability these assets will be tasked with other missions. In any case, the missile batteries assigned to US ground units could provide the initial firepower needed to degrade the port or base’s defenses. As US and allied ground forces continue to field batteries capable of firing Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles, SM-6s, and Precision Strike Missiles, they will be able to match the range of potential Chinese A2/AD systems forward-deployed to ports and bases. Both services need to train to operate these batteries from both naval and commercial ships.

A second, significantly cheaper option would be for naval forces to develop long-range, containerized loitering munitions similar to the Sunflower and deploy them from the proposed Marine Landing Ships Medium (LSM) or small merchant ships. The predicted collapse of global trade at the onset of a US-China war suggests that many merchant ships will be available.88Captain R. Robinson Harris et al., “Converting Merchant Ships to Missile Ships for the Win,” Proceedings 145/1/1,391 (January 2019), US Naval Institute, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2019/january/converting-merchant-ships-missile-ships-win. The United States should be able to rapidly produce a drone with Sunflower-level capabilities. These systems’ smaller payloads would minimize collateral damage in key international ports. If the Marine Corps continues developing the XQ-58A Valkyrie, the Fleet Marine Force could employ its derivatives from distances exceeding the range of Chinese weapons likely to be at contested ports.

Another option to overcome the tyranny of distance is pre-positioned warehouses that could supply fly-in forces ashore to counter the Chinese pop-up bases. However, this would require permission from both the host nation and major investments in pre-positioning facilities and equipment. Chinese intelligence will likely know where the pre-positioned equipment is located, enabling Chinese missile and drone forces to attack the warehouses or the unloading Maritime Prepositioning Ships as part of the opening volleys of the war.

If host nations will not permit pre-positioning of US forces in the region, or the United States chooses not to, missile batteries could be deployed on the proposed LSMs or merchant ships as afloat pre-positioned batteries. Marines and soldiers could be flown in to meet these ships and then operate from them. This would eliminate the requirement for host nation permission and reduce the vulnerability inherent in unloading.

The Marine Corps should also adopt the US Air Force’s Rapid Dragon concept to use C-130s and MV-22s to provide a longer-range strike capability than available from the F-35.89Max Hauptman, “Air Force shows off its Rapid Dragon cruise missile system on China’s doorstep,” Task and Purpose, July 26, 2023, https://taskandpurpose.com/news/air-force-rapid-dragon-mobility-guardian-2023/. The Rapid Dragon program loads cruise missiles onto pallets. These pallets are then air-dropped from the aft bay of a cargo aircraft. The missiles fall free, ignite, and proceed to their targets as normal. These platforms could deliver cruise missiles for a fraction of the cost of F-35s. The use of Rapid Dragon technology would also free up F-35s for other essential operations against the PLA. To further reduce costs, the United States should pursue the air force’s Grey Wolf/Golden Horde low-cost cruise missile program, which is a fraction of the cost of more advanced cruise missiles operated by the Joint Force.90“Rapid Dragon,” Air Force Research Laboratory, accessed X, https://afresearchlab.com/technology/rapid-dragon.

As Chinese long-range systems are eliminated, US and allied forces could close the range to conduct a suppression of enemy air defenses campaign against remaining Chinese air defenses. However, as the Ukrainians have demonstrated, mobile anti-air systems are exceptionally difficult to destroy. Allied forces will need to develop tactics, techniques, procedures, and equipment that will allow them to successfully engage mobile air defense systems. Once the long-range and anti-air capabilities have been stripped away, US or allied ground forces, in cooperation with host nation forces (if available), can clear the ports and bases of Chinese weapons.

The final, and perhaps most time-consuming, action will be mine clearance operations. Even with allied assistance, clearing mines—particularly modern smart mines—will be a major challenge. Further, China may elect to re-seed minefields using merchant and fishing vessels flying false flags. The US Navy currently severely underinvests in mine clearance capabilities, and this underinvestment seems unlikely to change by 2035.

Establish effective blockades to severely degrade Chinese international trade.

To reduce the strain on US naval and air power, the second mission—establishing an effective blockade—can be built around air-capable amphibious ships, container ships converted to operate light helicopters, operational light helicopter squadrons, Littoral Combat Ships (LCSs) with ASCMs (or containerized ASCMs aboard the amphibious ships), ISR assets, and Marine or army infantry units. In short, new units or equipment would not be required, but existing forces would need to be trained in planning and executing blockade operations.

The limited number of exits from the South and East China Seas significantly reduces blockade requirements. Additionally, crippling China’s economy does not require stopping all shipping—only large container ships, tankers, and bulk carriers, which are easier to track. With accurate intelligence on the movement of large Chinese commercial ships, US and allied blockade forces would be able to operate near the restricted passages south of the Bashi Channel.

Small task forces composed of helicopter-capable ships, infantry boarding parties trained to fast-rope, light helicopters, LCSs, or container ships armed with ASCMs and drones could be stationed to cover each of the major exits from the South China Sea. The United States must establish procedures and units for taking command of seized ships, moving them to a quarantine area, and passing control to a prize court to adjudicate their disposition.

If granted host nation permission, the Joint Force can establish support facilities near major choke points. These facilities would provide basing for persistent ISR of the choke points. They can also be used to resupply and maintain blockade ships and aircraft. If host nations along the First Island Chain refuse, maintaining the blockade will be more difficult but could still be supported from Guam and, if permitted, northern Australian ports. This approach would require the commitment of most of the US Navy’s large amphibious ships, which could be augmented by allied amphibious ships. While sufficient amphibious ships may be unavailable, container ships can be quickly modified to house light helicopters and boarding parties. The navy and Marine Corps developed this capability in the 1990s, designating the ships as T-AVBs. 91Mark L. Evans, “Wright III (T-AVB-3),” Naval History and Heritage Command, updated October 4, 2024, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/w/wright-iii–t-avb-3-.html.

Should maintaining a blockade at the First Island Chain become untenable, the blockade can shift back to the Malacca, Sunda, and Lombok Straits, as well as the passages north and south of Australia. These straits are very narrow: the Malacca Strait is only 1.8 nautical miles wide at its narrowest point, the Sunda Strait is 2.4 nautical miles wide, and the Lombok Strait is 5.4 nautical miles wide.92Fiona S. Cunningham, “The Maritime Rung on the Escalation Ladder: Naval Blockades in a US-China Conflict,” Security Studies 29, no. 4 (2020): 730–768 https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2020.1811462.

A final blockade line could be established at the Strait of Hormuz, Bab el-Mandeb, and Cape of Good Hope. Hormuz and Bab el-Mandeb are particularly narrow. Even from the Cape of Good Hope, the blockade force could interrupt trade between China and Europe or the Middle East. While the passages around Australia and the Cape of Good Hope extend for hundreds of miles, long-endurance drones and satellites can track large vessels and provide intercept paths for blockade forces.

The blockading force will challenge designated ships and direct them to prepare to receive a boarding party. Most commercial ships will comply to avoid the damage associated with being stopped by force. Many crews will likely agree to stay on board, particularly if they are paid at union rates and guaranteed a flight home upon arrival in port. If necessary, the blockading force could employ light attack helicopters to engage ships that refuse orders. When a target ship complies, Marines or soldiers could fast-rope onto the vessel as necessary to seize control and then direct it to a designated anchorage. Upon arrival, the ship could be turned over to contractors for anchor watch until it can be adjudicated by a prize court.