Swiss-EU economic relations in eight charts

In late 2024, Switzerland and the European Union (EU) concluded a new package of bilateral agreements. Here are some key figures on the long-standing economic links between the two partners.

New bilateral agreements between this country and the EU were announced on December 20, 2024, after several years of protracted negotiations. On the Swiss side, they are yet to be approved by parliament and the nation’s voters.

The latest deal has received a mixed reaction in Switzerland. Hailed by business and liberal opinions, the accords were initially criticised by labour unionsExternal link. The latter singled out the insufficient protection of wages and the liberalisation of the electricity market. In March the Swiss government adopted a package of measures to protect Swiss wages, which were backed by employers and unions.

The Swiss People’s Party opposes the new treatyExternal link. The free movement of people is a fundamental problem for the right-wing party, which has been trying for years to reinstate immigration quotas.

This article highlights the interdependencies between the economies of the EU and Switzerland as they are a central aspect of discussions on the bilateral treaties.

Switzerland is not a member of the EU. Neither does it belong to the European Economic Area (EEA) like Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein. None of this prevents Bern from having close economic relations with Brussels.

Economic and trade cooperation between Switzerland and the EU is regulated by a set of bilateral accords. These treaties have aligned a great deal of Swiss law with that of the EU and given Swiss businesses direct access to European markets.

“These accords go much further than a traditional free trade agreement,” explains Michael Fridrich, head of the economic and commercial section of the EU Delegation to Switzerland and LiechtensteinExternal link. “The free movement of people and mutual recognition of each other’s standards of conformity, for example, are elements not found in other agreements, and they are advantageous to both sides.”

Bilateral free trade agreement (1972): This accord marked the beginning of official relations between the two neighbours and aimed to eliminate obstacles to trade (only goods were included here).

Bilaterals I (1999): After Swiss voters declined to join the EEA in 1992, Bern and the EU agreed on a package of seven sector-by-sector accords. The most notable ones relating to trade were the agreement on the free movement of people, mutual recognition of conformity declarations, and access to several key sectors of the internal market (agriculture, transport, public tenders).

Bilaterals II (2004): Nine subjects were covered in these additional accords, such as the reduction of customs tariffs on food products and the end of systematic passport checks at the border thanks to the integration of Switzerland into the Schengen area.

Bilaterals III (2024): This package included two new agreements in the areas of electrical power and food safety. It also addresses institutional questions that had been left open up until that point.

A comprehensive review of the current situation regarding the bilateral treaties can be found in this article.

Switzerland is a small, rich, industrialised country with few natural resources, so it’s hardly surprising that it’s deeply involved in international trade – and this primarily with its neighbours.

According to the government, it is “well established” that the bilateral accords have “contributed extensively” to Switzerland’s good economic performance and that the country would have much to lose if the accords ceased to exist, says the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) on its websiteExternal link. SECO declined a request from SWI swissinfo.ch, saying it is not currently giving interviews on this topic and pointing instead to studies commissioned by Bern in the past few years.

The Swiss business federation economiesuisse also finds the bilateral accords with the EU to be “an essential pillar of Switzerland’s prosperityExternal link”. Other, more critical voices maintain that the real impact of the bilateral accords is hard to see from an economic point of view.

>>Read more: two opposing opinions on advantages and disadvantages of the bilateral accords with the EU from an economic perspective:

More

Bilateral path with EU is in ‘the interest of Switzerland and its economy’

More

Swiss-EU bilateral approach: not the economic boon it is made out to be

So what do the statistics actually tell us? Here are seven takeaways:

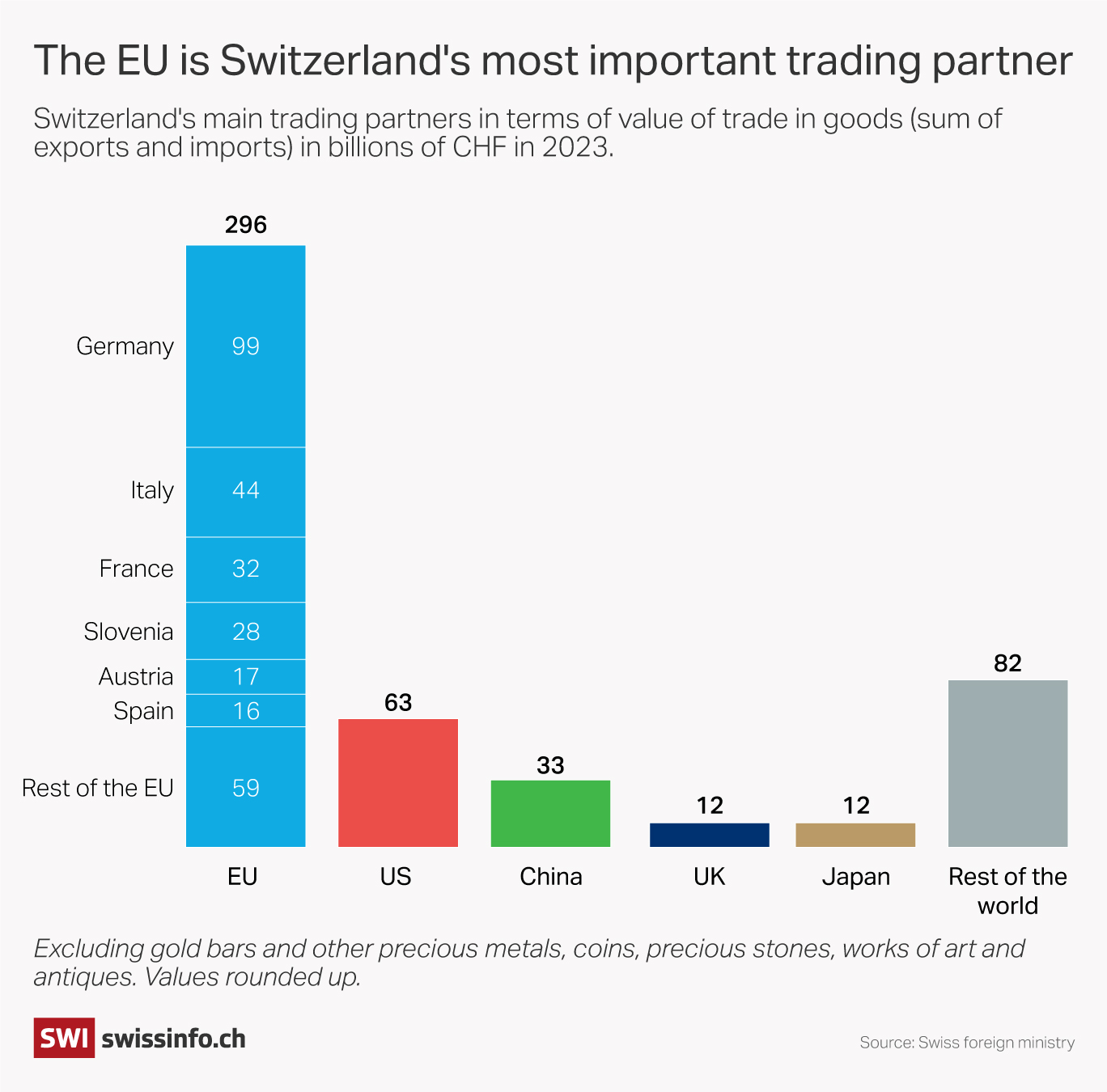

1. The EU remains the principal focus of Swiss trade

Trade between Switzerland and the EU has multiplied by 2.5 in the past 30 years, increasing from CHF115 billion ($130 billion) in 1993 to nearly CHF300 billion in 2023.

Between 1990 and the end of the 2000s, transactions with the entire EU represented nearly 70% of Switzerland’s international trade. This proportion has declined slightly, as other markets have gained ground, especially the United States (less than 8% in the period 1990-2000, but 13% in 2023) and China (jumping from less than 2% to nearly 7%).

But trade in goods with the EU remains dominant. It currently represents about 60% of all Swiss trade.

2. Geographical proximity is a key factor in Swiss-EU trade

Switzerland’s immediate neighbours are also its most important trade partners. However, Slovenia has climbed in the rankings over the past decade by making a name for itself in the pharmaceutical sector.

More

Swiss pharma’s big bet on Slovenia

According to a discussion paper from the foreign affairs ministryExternal link, one-third of Swiss trade with the EU involves border regions like Baden-Württemberg in Germany or Lombardy in Italy.

For Fridrich, geographical proximity is in general an important factor in business. It may become even more so when relations with other partners (such as the US) become more unpredictable.

Germany ranks second as a destination for Swiss exports, after the US, and the EU as a whole gets just under half (47%). This last figure has dropped over the past 30 years, down from 60% in 1993.

3. Switzerland buys most of its goods from the EU

Nearly 70% of goods imported by Switzerland come from the European Union; Germany is the main source country.

As for servicesExternal link, the EU is Switzerland’s principal trading partner as well. It accounted for 40% of Swiss exports and 45% of imports in 2023.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is a further indicator of the importance of links between Switzerland and the 27-nation bloc. Businesses in the EU – and the Netherlands above all – account for upwards of two-thirds (CHF601 billion) of FDI in SwitzerlandExternal link.

Swiss businesses investing abroadExternal link – for example, by operating subsidiaries – do this mostly within the EU, to the tune of CHF588 billion, or nearly half of total Swiss FDI. (However, considered on a country-by-country basis, the US is the main destination for Swiss investment.)

4. Switzerland is hardly an unsignificant partner for the EU

The internal European market is huge compared to that of Switzerland. The population of the EU is 50 times bigger and the economies of its member states are, taken together, 20 times greater than Swiss GDP.

However, superior purchasing power is an advantage for Switzerland, and the specialisation of its economy in high-value-added sectors makes it a force to be reckoned with.

The Alpine nation ranks fourth among trading partners of the EU (although the first three are far ahead of it). Switzerland accounts for over 7% of the bloc’s exports in goods and nearly 6% of its imports.

Switzerland’s trade figures with France and Germany are fairly modest (it ranks ninth), but it is the main trading partner of Slovenia – a full 20% of the latter’s international trade is done with Switzerland.

This is even truer for services. Switzerland ranks third as a trading partnerExternal link of the EU in services, behind the US and the United Kingdom. In 2022 it consumed 11% of the services exported by EU countries, and provided 7% of their imports.

Swiss businesses also carry a certain weight when it comes to investment in the EU. In 2022 Switzerland ranked thirdExternal link (9%), after the US and UK, both for inflow and outflow of FDI.

5. The pharmaceutical industry is crucial to Swiss-EU trade relations

Chemicals and pharmaceuticals are among the principal goods exchanged between Switzerland and the EU, accounting for over one-third of the total (CHF108 billion).

Switzerland ranks second as a supplier of pharmaceuticals to the EU after the US. It is the EU’s first-ranked supplier of gold and watches, and ranks third (after the US and China) as a source of precision instruments imported by the EU.

On the other hand, Switzerland imports from the EU a range of goods which it cannot produce itself, or cannot produce in sufficient quantity: cars, petroleum and furniture.

As for servicesExternal link, Switzerland imports more than it exports, for example, in tourism, IT and transportation. But it has the advantage in sectors where it is traditionally strong – finance (CHF9 billion) and insurance (CHF2.5 billion).

6. The balance of trade currently favours the EU

For years now, Switzerland has had a negative trade balance with the EU, which means that its imports exceed its exports – even in pharmaceuticals.

Yet according to an article published in 2018 by two SECO economists in the magazine Die VolkswirtschaftExternal link, this imbalance “is not an economic problem” but just shows the interdependence of the various national industries.

Manufacturing processes, the authors point out, increasingly involve components and stages sourced in other countries besides the country which will eventually export the finished product.

Switzerland itself imports materials from the EU that are used to make products it then sells to the rest of the world. This explains its higher volume of imports of chemical and pharma products from Ireland, for example.

Bilateral trade balances are therefore less revealing, these experts say, than the global trade balance, which is mainly favourable to Switzerland (by as much as CHF48 billion in 2023).

7. Europeans make up most of the imported workforce in Switzerland

Since 2002, when the agreement on the free movement of people came into force, citizens of the EU can live and work in Switzerland, and vice versa, as long as they have an income.

This agreement has modified the structure of immigration in Switzerland. Immigration is now dominated by citizens of the EU, mainly from neighbouring countries. Net migration from the EU to Switzerland in 2024 stood at 64,000.

Most of this immigration is for work purposes, as can be seen from the fact that it fluctuates according to the economic climate. With its many job opportunities and high salaries, Switzerland is an attractive destination for European workers.

Given the benefits of residency, a large number of European immigrants stay in Switzerland over the long-term. Their numbers have steadily increased over the past 25 years, reaching 1.5 million people in 2023 or 17% of the resident population of the country.

The number of European cross-border workers – that is, people who have their residence in a neighbouring country but cross the border to work in Switzerland on a daily or weekly basis – has increased from just under 163,000 in 2002 to about 400,000.

No European data is available that provides a similarly detailed overview of people migrating each year from Switzerland to the EU. According to non-exhaustive data from EurostatExternal link, close to 29,000 people who immigrated to the EU in 2022 had lived previously in Switzerland, but this figure includes all citizenships.

That same year, about 5,000 Swiss emigrated to GermanyExternal link and 4,000 people born in Switzerland emigrated to FranceExternal link, according to the migration statistics of those two countries. Less than 460,000 Swiss settled in the whole of the EU.

Of all the bilateral accords, the one on the free movement of people is the subject to debate in Switzerland, including on the economic dimension.

Opening up the labour market has created fears, especially in the border cantons, of downward pressure on wages and disadvantages for the local population due to increased competition on the labour market. But numerous studiesExternal link tend to conclude that the “accompanying measuresExternal link” adopted at the same time have prevented these adverse effects.

More

How free movement impacts the Swiss economy

As was the case in previous years, the most recent report from SECOExternal link concludes that the free movement “made it possible to meet the demand for labour that was not available in Switzerland, or not available in sufficient numbers”. Ongoing labour shortages in some sectors seem to back up this analysis.

Some voices outside nationalist circles criticise the restrictive nature of the free movement accord and are calling for a return to quotas, arguing that these would not prevent Switzerland from recruiting foreign workers as needed. But the authors of the SECO report say: “Quotas on immigration would lead to a reduction in the labour supply and push up recruitment costs”.

Fridrich, of the EU Delegation to Switzerland, says that the economic benefits of the various components of the bilateral agreements cannot be considered in isolation. “If Switzerland is seen as an attractive place for European companies to invest, it is also because they know that they will have no problem sending their staff if they set up a subsidiary here,” he says.

Edited by Samuel Jaberg/Adapted from French by Terence MacNamee/gw

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.