So explains Rabobank’s Gorjan Nikolik, following Trump’s decision to increase tariffs on Chinese tilapia imports from 25 to 45 percent and to introduce a 25 percent tariff on Canadian goods.

And its an issue that could be hugely exacerbated if US plans to introduce punitive port fees on Chinese-built and operated vessels come to fruition.

Tilapia tariffs

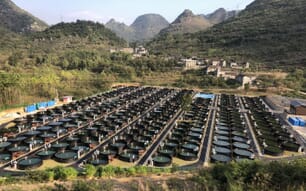

Given that 82 percent of the 209 million pounds of frozen tilapia that were imported into the US last year came from mainland China, it’s likely that the new 45 percent tariff will have a huge impact on the affordability of – and demand for – this product.

And, given the scale of the volumes involved, it’s unclear if and when it might be possible for other exporters to make inroads into this shortfall.

82 percent of the frozen tilapia that were imported into the US last year came from China

Although Indonesia could be poised to benefit and build on the 22 percent growth it experienced last year, Nikolik points out, it’s only exporting a tenth of the volume of China. Meanwhile Vietnam might be able to make up some of the shortfall with pangasius – there was a 36 percent increase in pangasius imports when the tilapia tariff was 20 percent. However, as Nikolik warns, Vietnam has a $123 billion trade surplus with the US, making it a potential target for high US tariffs in the future.

“If tariffs are imposed on both Chinese tilapia and Vietnamese pangasius, it could significantly impact the entire freshwater fish category in the US market,” he notes.

As there’s no way to make up the shortfall, Nikolik expects that US consumers will have to look beyond tilapia to other seafood species or switch to relatively affordable animal proteins such as poultry.

The US seafood market has so far partially been shielded by the fact that Trump’s victory in November on the back of his pro-tariff agenda meant that US importers of frozen tilapia fillets stepped up their purchases by 30 percent increase from November to December and a 51 percent increase compared to December of the previous year.

However, it’s harder to see where a longer term fix could be. Nikolik notes that Brazil, India, and Indonesia are seen as potential long-term suppliers if they continue to avoid high US tariffs – which he believes is highly possible given that they are viewed as geopolitical allies by the US. However, they currently only supply very small volumes of pangasius and tilapia to the US and would need time to develop export industries for these fish. As a result, if the import tariffs remain high and other regions aren’t able to take up the slack, Nikolik believes that US domestic production of tilapia – currently a niche sector catering largely for live sales – could also develop.

“The main reason it's never been done is because they are much cheaper to produce in countries like China. But if there are such high tariffs and countries like India, Brazil or Indonesia do not fill the gap, why wouldn't the US grow more themselves?” he asks.

If Canadian goods are hit with a 25 percent tariff US consumers are likely to face a significant uptick in salmon prices © BCSFA

Canadian salmon concerns

Canada’s salmon farming sector – which has had a rough few years due to diminishing domestic support – will be hit extremely hard if Trump does go ahead with the potential 25 percent tariff on imports from the USA’s northern neighbour.

Indeed, as Nikolik points out, Canada supplied 144 million pounds of the 283 million pounds of fresh whole salmon imported by the US in 2024.

And, as he observes, if a huge tariff on Canadian salmon is introduced in April, it would be difficult for the other salmon producing countries to fill the void – due to the inelastic nature of salmon supply, caused by the two-year grow-out process, their limited production capacities and the fact that they would rely on air freighting their fresh fish to the US, which is more expensive – especially for unprocessed whole fish.

“It’s really, really difficult for other countries to increase their fresh salmon exports to the US substantially in the short term. I think they will all do a little bit more, but they're flying by plane, so there is really no substitute for Canada. The prices will really have to go up quite a lot before countries like Chile, Scotland, Norway, Iceland and the Faroe Islands, will increase their exports to the US,” Nikolik points out.

Better news for shrimp?

While shrimp exporters targeting the US market have suffered from the lobbying power of America’s wild-catch shrimp sector. They look likely to get off comparatively lightly in terms of a new batch of tariffs.

As Niikolik explains: “Shrimp is the largest species consumed in the US and also the largest seafood import item. The two leading exporters, India and Ecuador, have very little trade surplus with the US and thus are less likely to targeted by tariffs, at least based on that criteria. And India, the number one supplier to the US, is also a major geopolitical ally for the US in Asia. Given the elastic supply of shrimp. even if there is a tariff on some of the other producers such as Vietnam, then the others can fairly easily fill in the supply gap.

“After years of suffering from countervailing and anti-dumping duties, at the moment it looks like shrimp may be the species least likely to be impacted.

The move is seen as a bid to spur a renaissance of the US shipbuilding industry, which is dwarfed by China's © Shutterstock

Picking a fight with Chinese shipping

While the prospect of increasing US tariffs is likely to throw seafood markets into turmoil, there’s another – perhaps even more destabilising – prospect for world trade and geopolitics potentially on the horizon.

As Nikolik’s colleague, Michael Every - who specialises in macro-economics - explains in a new paper, recent radical proposals from the US Trade Representative (USTR) on introducing punitive port fees for Chinese-built and operated vessels have shocked the global maritime industry.

Indeed, in February the USTR proposed:

- To charge China-built ships entering US ports $1,000 per net tonne of weight, up to a maximum of $1m (or up to$1.5m for China-built and operated ships).

- To charge any ocean carrier using China-built ships the same rate for using US ports, even if they do not enter them, depending on their ‘China share’, with a sliding 25 percent, 50 percent, 75 percent, and 100 percent scale.

- To impose cargo quotas for US exports to be carried on US flagged and operated ships: 1 percent in 2025; 3 percent by 2027; 5 percent by 2028, with 3 percent on US-built, and flagged, and operated ships; and 15 percent by 2032, and 5 percent on US-built, flagged, and operated ships.

The shipping sector has raised widespread concerns about the plans, with the World Shipping Council stating that “98 percent of ships that call on US ports could be affected by USTR’s proposals. Policymakers must reconsider these damaging proposals and seek alternative solutions that support American industries.”

“The proposed US port tax operates on the same principles as a goods tariff, which are about to rise significantly in the US. Just as the US is apparently not going to back off from these tariffs, despite industry complaints, stock market wobbles, and the risk of trade wars, so it may not back off from these new port charges either,” the report concludes.