This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

There are certain towns I call ‘bro towns,” the sociologist Jane Ward told me. We were sitting in the kitchen of her sunny home in Santa Barbara, California; the yard outside was ringed with citrus trees. Ward, a young-looking 51, in a plaid romper and Birkenstocks, had her sandy-blonde hair and a few natural grays tucked behind her ears. Maui is a bro town, she explained, with its surfer culture and white guys in dreadlocks shouting “braahh.” Lake Havasu, in Arizona, is a bro town, with its spring-breakers and wet-T-shirt contests. And Santa Barbara, home to the No. 1 party school in America, UCSB (also known as the University of Casual Sex and Beer), where Ward is a professor, is definitely a bro town. “It has an ethos that just influences everything about life,” she said. “You know, how people drive, what people wear, how the men walk, how people date — everything.”

Ward is UCSB’s chair of feminist studies, and she was preparing for the first day of her new seminar, an intro to her area of expertise: straight studies. UCSB presents something of a perfect sample group for her work. Sitting along the Pacific Coast, it’s one of the only colleges in America that has its own beach, and male students can be seen riding shirtless on cruiser bikes — no hands! — with surfboards under their arms. Girls work on their tans after class. Isla Vista, the square-mile main drag of the school’s party scene, has long been a popular scouting location for reality porn. The vibe of the campus, at least on the weekends, is reminiscent of the scene in the Barbie movie where the Kens have turned Barbie’s house into the Mojo Dojo Casa House and decided to throw a party.

It was a Monday in January, the first one back after winter break, and the temperature was, per usual, a perfect 72 degrees. Over on the main quad, blonde frat guys with clipboards were recruiting potential members, as young women practiced K-pop dance moves, and a student from the psych program solicited responses for a dating survey. In a fourth-story classroom, Ward and I joined 28 undergraduates as they moved their desks into a circle. They looked a bit different from their peers outside. Most were dressed in baggy jeans and oversize T-shirts; there were a few septum rings and at least one “Fuck Tuition” sticker on a laptop. The course was formally called Critical Heterosexuality Studies, and Ward was about to become its lesbian sage.

“I feel like this class will answer a lot of, like, Why are they like that?” a student named Anthony told the group. He’s a global-studies major and identifies as gay.

“I feel bad for some of my straight friends,” said Sarah, a comparative-literature major from Long Beach. “They’re like, ‘Oh my God, my boyfriend got me flowers for the first time in two years.’ I’m like, ‘Can we raise the bar?’”

Dani, a psychology and brain-sciences major from Dallas who is bisexual, confessed that she’d observed herself behave in ways that disturbed her when she dated men — she was more submissive, more self-conscious, inattentive to her own needs — and wanted to understand why. Julia, who cheekily revealed that she is “actually straight but queer enough to be here,” said she thinks that a lot of straight relationships create that kind of insecurity. Simran, a feminist-studies and psychology double major, who described herself as “constantly confused about my sexuality but definitely not straight,” said she has trouble imagining being a parent without a man in the picture: What was that about?

“Let’s try to answer that in the next few weeks,” Ward said. She was carrying a water bottle with a pink sticker reading “Good Luck, Babe!” — the title of a Chappell Roan song about a woman who ends up with a man, and, well … good luck with that.

“In this class, we’re going to flip the script,” she went on. “It’s going to be a place where we worry about straight people. Where we feel sympathy for straight people. We are going to be allies to straight people.”

To Ward’s knowledge, and mine, her class is the first course of its kind — approaching straight culture head-on as its primary subject. Strangely, few academics seem to have been drawn to the topic. Since the early days of sex research, from Freud to Kinsey and now today’s vast world of scientists and theorists, scholars have been trying to understand the elements of sexual and romantic desire, but investigation has tended to focus on deviations from the perceived norm: Was being gay a choice? Is sexual preference a spectrum? Does homosexuality have its roots in nature or nurture?

Heterosexuality tended to be studied only as the background condition of other phenomena — in the context of sexual assault, domestic labor, sexual satisfaction — and there was a brief period, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when some feminists demanded it be studied as a political institution, one they believed upheld the patriarchy. But as the study of LGBTQ identity and relationships has continued to expand and deepen, the world of heterosexuality, among academics, has remained largely unexamined: It’s the wallpaper against which other exhibits are hung; it just is.

Lately, it seems this may have been a mistake. After years of headlines about Gen Z being the most progressive generation in history, and after decades of what seemed to be broad, mainstream progress on sex and gender equality, a cold backlash has arrived, hitting the socially liberal among us like a Saratoga ice-water facial plunge.

We’ve all been familiar for some time with the tradwives, the influencers preaching reborn domesticity to the masses, describing daily chores with saccharine captions about the joys and freedoms of submitting to men. And we’ve known about the popularity of Andrew Tate, the self-proclaimed misogynist and alleged human trafficker, and less violent but still noxious pod men. The online world seems to get weirder and more retrograde about heterosexuality every day. Idealized masculinity has become more aggressive, more jacked up, and also more high maintenance — have you heard of mewing? — while femininity gets ever “softer,” more nurturing and domestic, and somehow still more sexy. It seems that almost weekly, there’s yet another trend, or term, or meme promoting traditional gender roles: Recently, for example, there’s been talk about men needing to make themselves into “masculine containers” for “feminine surrender” if they want a prime companion.

There was a way to see all this as “online” reality and not necessarily representative of real culture. But in November, Trump’s victory revealed, in full frontal, that young men have become distinctly more conservative — and that there’s a new and stark political divide between them and their female counterparts, who have remained largely liberal. Polls leading up to the election showed the widest gap in political views in American history.

Enough young American women are fed up with the current realities to make a sizable trend of their own, declaring themselves “boy sober” or “voluntarily celibate” or proclaiming themselves as part of the 4B movement, born in South Korea, which rejects all sexual and romantic relationships with men. (Some have taken to painting themselves in “unapproachable makeup” — makeup so severe it keeps guys away.) Older straight women, who seem to be experiencing many of the same frustrations as women 50 years ago, are tearing through divorce memoirs and novels — most often stories of liberation.

In 2019, the gender scholar Asa Seresin coined the term heteropessimism to describe straight women’s “performative” expressions of regret, embarrassment, and hopelessness about their hetero lives. (It is performative, Seresin writes, not because it is insincere, but because it is “rarely accompanied by the actual abandonment” of straight relationships.) Ward refers to all this anguish as “the tragedy of heterosexuality,” which is also the title of her 2020 book and the text on which her straight-studies course is based. Despite the half-century of supposed advances since the sexual revolution, she says, heterosexuality is still a mess.

Back at her house, overlooking her neighbors’ terra-cotta rooftops, she said, “I think it’s really a tough pill to swallow for many straight women.” She made a bit of a pained face. “That the hope that men were getting better with each generation — that, you know, as time went on, they would be more committed to gender justice or equity. That it simply did not come true.”

Ward approaches her subject through a mix of historical research, current cultural analysis, light ethnography (she’s observed classes for male pickup artists), and a heavy dose of personal reflection as a queer woman who spent some time on the other side. She finds that straight relationships are full of contradictions, antagonism, and boredom; they are “erotically uninspired,” paralyzed by “punishing” gender expectations, and burdened by countless daily injustices. The common narrative about gay relationships and gay life, Ward writes, is that it’s a difficult path, and she admits it certainly can be hard. But she believes straight women actually have it worse — that the cards are fully stacked against them.

Her work seeks first to locate the root of the problem: Is it in the customs and rituals of heterosexuality? The way that it’s been marketed and sold in particular cultures? Is it in individual choices, ones we can control? She also hopes her work can somehow lead the way to a better future.

“We have decades of evidence, coming out of feminist research, that heterosexuality often fails women,” she told me. Her wife, a high-school teacher, was in the bedroom on a Zoom call; their teenager was off somewhere playing video games. “It promises things that it doesn’t deliver,” she said. “And now we also know that it’s popular for straight women to talk about that. So for me, the big question is, Is talking about the problem actually going to do anything to address it?”

To consider that, she likened heterosexual love to eating disorders. “Can you teach a student to see the cultural conditions that are leading that student to hate their body and help support them to make a different set of choices?” she asked. “Yes, absolutely. I think that happens all the time.”

Ward is a product of her own heteropessimism, in a way. She grew up in Whittier, a suburb of Los Angeles. Her mom, a hippie, stayed at home, taking care of Ward and her brother; her dad, a firefighter, struggled with substance abuse. They divorced when she was 12. Ward dated boys in high school and college and considered herself straight until grad school, when she broke up with her boyfriend and hooked up with her female best friend. In terms of pure attraction, she felt bisexual, but the more she considered it, the more she thought, Why would I ever settle for people who I don’t have basic value alignment with, which is most men? “Chosen,” she told me, was not the exactly right word for the life she’d ended up with. It was more that she had “cultivated queerness.”

Ward met her wife, Kat, in the early aughts, when both were living in L.A. and Ward was performing with a queer burlesque troupe called the Miracle Whips. Kat was in the audience at one of the shows and approached her after. “I basically lived a double life,” Ward said. By day, she drove an hour to UC Riverside, where she was an assistant professor of sociology, teaching undergraduates, and where her colleagues knew nothing of her evenings dancing in pink ruffled bloomers under the name “Virginia Dentata.” (You know, like the mythic toothed vagina.)

Ward’s ideas about straight culture began to come into focus a few years later, after she gave birth to her and Kat’s child. On leave from Riverside — she was now in the gender-and-sexuality-studies department — she found herself desperate for connection. “I was losing my mind,” she said. She joined a “MOMS Club,” a national support group for at-home moms that has chapters around the country — an embarrassingly normative solution.

As the token lesbian in many of the small-group meetups, Ward seemed to draw women toward her for straight confession. Their romantic relationships with men were characterized by resentments: over the crushing unequal division of domestic labor, over their husbands’ infidelities, over so many emotional needs unmet. “It was actually kind of heartbreaking,” she told me. As Ward would write later, the straight culture she observed relied “on a blind acceptance that women and men do not need to hold the other gender in high esteem as much as they need to need each other” and “to learn how to compromise and suppress their disappointment” in one another.

At the time, Ward had a personal blog where she wrote about parenting, raising chickens in her backyard, and, on occasion, feminist parenting books. In 2011, she tapped out a post titled, “It’s Not that ‘It Gets Better’” — a nod to the “It Gets Better” queer mantra of the time — “It’s That Heterosexuality Is Worse,” laying out the thesis that would come to drive her work. Absorbing straight women’s private complaints and teaching women’s-studies courses year after year — continually revisiting the facts of domestic violence, rape, inequities in child-rearing and the home, marital unhappiness and antipathy — had made it very clear: Straight women’s lives, she wrote, are “very, very hard.”

For a Blogspot that usually reached a few thousand L.A. moms, the post went viral, and it soon made its way to other academics, who began to offer their thoughts in the comments; some said they were assigning it to their students. Ward already had a book project in the works — her 2015 title, Not Gay, about sexual encounters between self-identified straight men — but she knew a critique of hetero relationships had to be next. As she began digging into the new work, she noticed she would often avoid telling people what she was studying. “It was embarrassing to tell straight people,” she said, “because they were going to feel immediately judged. And it was embarrassing to tell queer people because they were going to be like, ‘Why are you spending time on this? Don’t straight people already take up enough space?’”

In reality, both theoretical sides were right. Straight culture did already consume a lot of space — it was the default in government policies and health care and Hollywood and everything else. That was precisely why she thought it deserved real academic scrutiny. And she was judging straight people — gently, as she saw it. In the book, Ward is careful to assure readers that her analysis is not really about heterosexuals themselves — that it’s not even really about heterosexual sex. (She does point, wryly, to studies that show many straight women actually find penises “unattractive” and “prefer to gaze at naked women when given the option.”) Her criticism, she stresses, is of the ever-present sexism: how it’s embedded in even “the most ‘liberated,’ ‘loving’ heterosexual situations.”

The Tragedy of Heterosexuality came out in the fall of 2020, when a generation of working women were about six months in to being pushed back into their homes to care for their children during COVID. It took a while for the book to reach a mainstream audience, but over time, Ward began hearing from women who told her she’d articulated precisely what they were feeling. “I’m leaving my husband,” a childhood friend she hadn’t spoken to in 35 years DM-ed her, wondering if Ward had any tips for how she could meet women. A reality-TV producer suggested that Ward could star in a “Supernanny meets Queer Eye” show, going into straight people’s homes and correcting their behavior, while another proposed she host a type of queer Love Island, where hot young straight people would be dropped off and given “queer” challenges, like trying pegging or cross-dressing. (She was open to the first project, though it didn’t materialize.)

As time has gone on, the cultural landscape has seemed to confirm Ward’s perspective more and more. Recently, she’s been amused to learn that Gen Z has a hashtag that refers to “compulsory heterosexuality” — the idea that women are socially conditioned to be straight, a concept she’d been teaching for years, originated by Adrienne Rich. Signs you might be “experiencing” #CompHet, according to TikTok (“the people’s DSM,” Ward jokes) include “confusing attractiveness with attraction,” seeking male validation, and liking the idea of a boyfriend but not the boyfriend himself.

When we spoke, data had just come out showing that more and more people are identifying as queer. According to Gallup, nearly one in ten adults in the U.S. identifies as LGBTQ+, and the increases have been driven in large part by young people and by bisexual women. I asked Ward what she made of those figures.

“That’s just so fascinating,” she said. “Because it’s like, ‘Well, do you think something’s in the water?’ Or is it possible that young people are choosing another way?” She knew she couldn’t really use the data to assess attitudes toward heterosexuality — it was too much of an extrapolation. “One thing we could measure, though,” Ward said, “is how much women are complaining. And they’re complaining a lot.”

A few weeks later, I joined Ward’s class again, this time over Zoom, right as she was explaining that “heterosexuality is never just about sex. There’s a whole ideological apparatus that gets built around it.” Another word for ideological apparatus, she said, might simply be culture—and straight culture could be seen everywhere. It’s there on T-shirts for grooms-to-be that proclaim “Game Over”; it’s in “choreplay”—when women reward their male partners with sex for doing basic household tasks. It’s in the way that young men joke that pleasuring a woman, or expressing too many feelings, or simply liking your girlfriend too much is “gay.” At UCSB they call that a “simp,” a student named Charlotte told me later.

Imagining themselves as straight people in such a world, it would be hard not to despair. In fact, the varieties of hetero despair were a conversation unto themselves. There was broad heteropessimism, but there was also the specific grief of straight women who want to improve their relationships with men but fail to see their problems as part of a much larger system. Without that recognition, Ward explained, they were doomed to fail again and again. They might turn to the “heterosexual repair industry”: the world of self-help texts, conferences, and coaching that frame trouble in straight relationships as individual failings of personality and perspective and often encourage women, ultimately, to double down on traditional gender roles (or, as Esther Perel has advised, to switch up the same old tired nightgown). Heterofatalism, on the other hand, was the grief that comes from seeing the larger picture — from knowing that the whole institution is rigged against women. Heteroresignation described one possible outcome of fatalism: giving up and giving in. Women who surrendered in this way might be stuck dealing with “normative male alexithymia” — the straight-male inability to articulate emotions in words. They might come across their share of “emotional gold diggers”: men who need their female partner to be their lover, mother, best friend, and therapist.

So women were damned if they knew, damned if they didn’t, and damned if they stayed — but what if they went? In straight studies’ first class, Ward had referred to what she called the “uncanny attachment” people have to heterosexuality, a topic she also discusses at length in her book. They return, she writes, “after no end of complaint or disappointment, straight back to their original form.” She pointed out that, typically, when there is general consensus that something is flawed or disappointing — like the service at a business, say, a restaurant, or like a product — maybe a car — the people responsible try to fix it. And if it isn’t improved sufficiently, patrons and consumers reject it. We consider it failed and move on.

Of course, heterosexuality is not quite as easily replaced as yet another natural-wine bar or a cybertruck. Wasn’t heterosexuality as immovable a condition as homosexuality — however immovable that really was? The idea of a helpless return to straight partnership sounded pathetic, at least sad, but could it really be considered uncanny, unexplained?

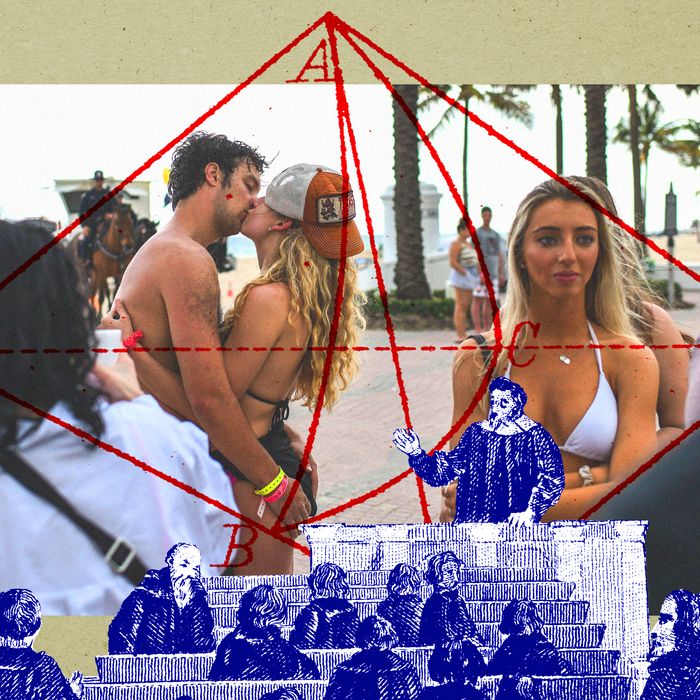

To illustrate this perpetual return, earlier in the semester, Ward had projected two side-by-side photos onto the screen at the front of the class. One was a still from the movie Waiting to Exhale, the 1995 romantic comedy: Angela Bassett was pictured walking toward the camera, in a white blazer over a black lace corset, as a white BMW erupts in flames behind her. The second image was a still from the album-length video that accompanied Beyoncé’s Lemonade 21 years later, in 2016 — from the portion that paired with the song “Hold Up.” Beyoncé, in a tiered yellow dress by Roberto Cavalli — which some speculated was intended to invoke the Yoruba deity of love — is seen mid-strut, holding a baseball bat, moments after smashing a car window, as another car burns behind her.

Both characters, Ward explained, had been wronged by their men. She asked the class what they thought the point might be of looking at the two photos together. One student offered that it might be to show “the exasperation of these problems for black women specifically.” In part, Ward replied; “Black women have often come to represent the ‘survival’” — she added air quotes here — “of enduring bad men.” But what else?

“Because,” another student suggested, “it’s not just like a recent thing but like a recurring historical thing?”

“Yes!” Ward said, banging her hand on a desk. “Because this shit happens over and over and over, with every generation. Every generation of women has their epiphanic moment where they realize this shit is not worth it. Every generation of women has the icon who burns all the man’s stuff. And so part of the tragedy is we don’t learn.”

“We” was interesting here. If some women could “learn,” and learning meant leaving men behind, Ward was one of them. But what about everyone else?

Later, I pressed Ward on this: In all this serious study, what does she say to those who might think she’s not taking straight attachment … seriously?

Ward explained that she has long argued that sexuality is more of a choice than modern society generally admits. She also believes that women specifically — many more than we would think — are straight by cultural default and not out of true desire. “I want to think that the compulsion is like, ‘Well, I’m attracted to men,’” she said. “And if that’s real, then great!” But too often, she says, when she asks women why they are with men, she gets some version of a blank stare. In other words, in Ward’s view, there is a lot of #comphet.

This of course still left the question: What about “real” heterosexual women? It seemed fair to assume that they exist. “Ultimately, the way I will measure success is not whether all of these young women become lesbians,” Ward said, laughing. Navigating the structural problems of heterosexuality could “look like choosing to partner with women,” or it could “look like telling your husband, ‘You are going to have to do your part.’” The structure itself would only ever change, she said, if a critical mass of women chose one or the other — or both.

In the last chapter of her book, Ward argues — as she would in the last class of the semester — that women who continue to be with men should consider taking a cue from queer people and consciously build new rules and rituals. It’s not a new concept: Feminists proposed it at least as far back as the ’70s, and in the ’90s, the feminist writer Naomi Wolf (a heterosexual)— before she fell off into conspiracy-theory land — proposed what she called “radical heterosexuality.” In Wolf’s vision, women needed to first become financially independent and therefore free to leave. Marriage — at least the kind presided over by the state — would be abolished in favor of something more like queer commitment rituals (gay marriage was not yet legal), and straight men would be mandated to disavow their patriarchal privilege (good luck). Both men and women would need to reject their “gender imprinting” — that is, their “erotic investment” in traditional roles, whatever that meant.

Ward’s version of the concept is called “deep heterosexuality.” For straight women who want to begin down this road, the first step, she says, is having to answer the same questions that gay people have been forcibly confronted with for so long: What propels them toward the opposite sex, despite all the difficulty? And what does being straight do for them?

The prodding — half-ribbing — was maybe in some ways another sidestep. (And weren’t straight women, as Ward’s work observed, subjecting themselves to this all the time?) But her students were onboard. “One thing that made me determined to take this class,” said Alan, a psychology and brain-science major originally from China, “was that it seems to me like a comeback.” Alan is gay, and his parents don’t know he’s working toward an additional major in feminist studies.

A comeback? Ward asked. What did he mean?

“It’s a comeback because people have been researching and studying homosexuality for so long,” he said. “And now it’s us using their methods and analytical tools to study them.” The master’s tools, as Audre Lorde would say. Her conclusion was that they actually couldn’t take down the master’s house. But Alan saw other benefits: “It’s giving revenge plot.”

More on Dating

- Who Would Ghost Drew Barrymore?

- Are Mariah Carey and Anderson .Paak Dating?

- ‘The First Great Date I Had After My Divorce’