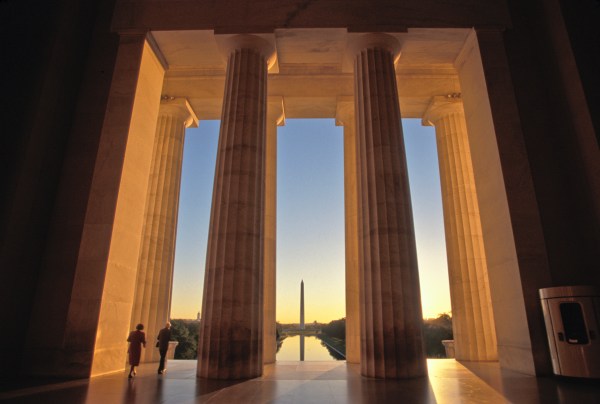

Among the 36 executive orders President Donald Trump signed on his first day in office was one document that stood out as strangely … aesthetic. Alongside directives involving such controversial subjects as birthright citizenship and “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” President Trump issued a memo commanding the General Services Administration to revise its “Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture,” and ensure that future federal buildings are built in a way that “ennoble[s] the United States and our system of self-government.”

It’s a lofty goal, and the memo has a specific purpose in mind. Seeking to revive a defunct order issued during Trump’s first administration, it marks a repudiation of the architectural styles known as Internationalism and Brutalism, which for 75 years have been the standard forms for federal office buildings, and which long ago became associated with gloomy officialdom. Nothing says “mechanized bureaucracy” more than the repetitious rectangles and aggressive flatness of International-style boxes such as Chicago’s Dirksen Courthouse or Brutalist behemoths like Washington, D.C.’s FBI headquarters. Therefore, in their effort to make America great again, nationalist conservatives have seized the moment to officially replace these modernist styles with more traditional designs. But that’s where the trouble begins—because what one considers the appropriate “tradition” is a loaded matter.

When they started working in the 1930s, pioneers of Internationalism such as the Swiss Le Corbusier and the German-born Ludwig Mies van der Rohe thought what they were doing was ultra-democratic: sweeping away the pomposity of marble columns and allegorical statues and idealizing straight-lined mass-production in order to create “machines for living.” Brutalists—who began working in Britain in the 1950s—also thought of themselves as making accessible spaces that reduced clutter and pointed toward the future.

The artistic avant garde liked glass-and-steel Internationalism and poured-concrete Brutalism, and midcentury government bureaucrats embraced these styles as cheap to build and easy to maintain. But Americans never liked them. As early as 1934, when Edward Durrell Stone built the Ulrich Kowalski House in Mt. Kisko, New York, neighbors hated it so much they passed a zoning ordinance banning modern architecture. A decade later, Elizabeth Mock, director of the Museum of Modern Art’s architecture department, confessed that “there has probably never been an architectural movement more deeply distrusted by the public” than the International Style. It struck people as soulless, even cruel, and the term “Brutalism”—which initially referred to a technique for treating cement—rapidly came to epitomize the way its bulky forms can loom and browbeat.

Nevertheless, government planners stuck to these styles, in part because they conveyed a sense of authority—monuments to power for power’s sake, devoid of democratic humility or human sympathy. That resulted in an architecture that spoke of bureaucracy rather than beauty. Art critic Robert Hughes once called New York State’s International-style capitol complex, Albany Mall, “the scariest new monument that I know,”—a place that dominated the citizen, rather than welcoming him as an equal participant in government. Even worse is Boston’s Brutalist City Hall, an asymmetrical conglomeration of smog-colored rectangles, which intimidates to an almost Soviet extreme. It was recently ranked the fourth ugliest building in the world.

“Has there ever been another place on earth,” novelist and art critic Tom Wolfe asked in his anti-Internationalist polemic, From Bauhaus to Our House, “where so many people of wealth and power have paid for and put up with so much architecture that they detested as within [America’s] blessed borders today?” Trump’s 2020 executive order put it more plainly. Modern public architecture, it said, “lacked distinction.”

This all matters because, as the 17th-century English architect Sir Christopher Wren once said, architecture “has [a] political use. Public buildings being the ornament of a country, it establishes a nation, draws people and commerce; makes the people love their native country, which passion is the original of all great actions in a commonwealth.” But there’s no evidence that Brutalism or Internationalism had these effects on Americans.

Trump’s 2020 order did not stop at rejecting such designs. Instead, it went on to prescribe a solution, requiring that future federal buildings be erected in “traditional and classical” styles, defined as Greco-Roman, Renaissance, Beaux-Arts, and Georgian. The order also included a list of architects whose work was to be imitated going forward. It included Daniel Burnham (designer of Washington’s Union Station), John Russell Pope (who built the National Archives) and Charles McKim (architect of Boston’s Public Library). None were born after 1881.

What’s striking about this list of officially acceptable builders is the name it glaringly omitted: the most beloved—and most American—of all architects, Frank Lloyd Wright.

During a career that lasted seven decades, Wright totally revolutionized architecture, spurning the Neo-Classicism that the upper classes had decreed to be official “good taste” in the 1890s, and offering instead a style that was at once futuristic and welcoming. He became not only the greatest architect in American history, but the only one many Americans today can immediately name.

Wright agreed with Wren that a nation’s values are reflected in its buildings, and that buildings can, in turn, shape the public’s social and political attitudes. But where the monarchist Wren believed in using architecture to propagandize about tradition and authority, Wright aimed to do the opposite. An acolyte of the democratic spiritualism of Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson, he spent his career designing buildings that celebrate individualism and respect the landscape. He liked to call it “Organic Architecture,” or “human scale.”

This stood in contrast with the imitation Roman temples and French chateaux favored by Neo-Classicist and Beaux-Arts architects. Where the aesthetic ideal of these designers was traditional order, and that of the Internationalists and Brutalists was precise and plain-spoken candor, Wright’s Organic Architecture prioritized mutuality. It was built around relationships—between buildings and the land, between homeowners and the home, between the inhabitants and each other. It was individualistic, but not arrogant; it sought harmony with nature and human beings. That made it, more than anything else, an architecture befitting American democracy.

Consider Wright’s 1936 Herbert Jacobs House in Madison, Wisconsin. A long wooden wall acts as a screen against the street, and its front door is concealed. On the opposite side, its large windows look out at a backyard garden. These features create a sanctuary that prioritizes the owner’s privacy and uniqueness. Other features of the house, however, are strikingly public: its open plan and the smallness of its bedrooms mean most of its area is shared, centered around a brick hearth. Thus, with few doors to lock oneself away, the inhabitants are gently pressured to come together for conversation.

The guiding principle of the house is simple: “a man’s home is his castle.” And Wright strove to ensure that it would be affordable, so that common people could enjoy the kind of dignified retreat that only the rich had previously enjoyed.

This was an architecture rooted in distinctly American values—so much so that Wright named it the “Usonian” style—an acronym for “United States of North America,” and a direct refutation of “International.” “Individuality is the most precious thing in life,” he explained in his Autobiography. “An honest democracy must believe that it is. [And that’s] the thing Usonia is going to fight, tooth and nail, to preserve [against] … the superficial, fashionable standardizing … calling itself the ‘international style.’”

Organic Architecture, therefore, always had a political element—but an unusual one, in that it did not highlight official authority. On the contrary, it fostered the democratic ethos Whitman articulated in a lyric that Wright ordered cast in concrete and placed at the entrance to his Arizona home, Taliesin West. Addressing Americans, Whitman wrote:

The grandeurs of the past are not for you

But grandeurs of thine own

deific faiths and amplitude absorbing, comprehending all,

all in all to all.

Wright, too, rejected the “grandeurs of the past” in favor of building environments that would balance public and private in a specifically American way: a grandeur of America’s own.

He could channel these principles into public buildings as well as houses. In 1957, he proposed a new Capitol for Arizona, which represented his last word in democratic-individualist architecture. “Oasis,” as he called it, featured spaces for the Governor, Legislature, and Supreme Court, but also for art displays and community meeting rooms, as well as office wings enclosing greens and fountains. In the center, a garden of desert plants helped integrate the building with the landscape, all shielded from the sun by a vast, perforated, copper latticework supported by onyx columns. It was undeniably impressive, yet accessibly democratic—the “grandeurs of thine own” that Whitman prescribed.

Wright’s idea of what government buildings should look like was entirely unlike the Renaissance or Neo-Classical styles that preoccupied previous generations, styles that had originally been designed to dominate and to reinforce hierarchies—fundamentally anti-democratic motives. That had led Wright’s teacher, Louis Sullivan (the father of the skyscraper) to denounce pillared, pedimented Neo-Classicism as “alien” to American democracy—an architecture “that turns its back on man.” In the 1890s, Sullivan called for an alternative, not derived from ancient dictatorships or Dark Age theocracies, but instead tailored to “a civilization based upon ideas thrillingly sane.” American democracy, he wrote, had freed “the power of constructive imagination” of countless millions, and the country’s architecture should reflect that. Wright agreed, but added a caveat: democratic-individualist architecture should not become so imaginative as to lose sight of the earth. So, instead of skyscrapers, he designed buildings that hugged the ground and emphasized the horizontal—a metaphor for the principle of equality.

These sentiments placed Wright at odds with Internationalist and Brutalist architects, who thought of buildings as, in Le Corbusier’s famous phrase, “machines for living.” Wright thought that standardizing buildings as if they were mere mechanisms would inevitably make people think of themselves as mere mechanisms—a singularly inappropriate idea in a democracy. “We are eventually going to have as citizens machine-made men, corollary to machines, if we don’t look out,” he said. Architects should prioritize “poetic tranquility instead of a more deadly ‘efficiency.’”

Thus, if any architectural style should be prescribed as “proper” for American public buildings, it is Wright’s Organic Architecture, which sought to express the values of individualism and mutual respect, instead of the intimidation and conformity that characterize Greco-Roman, Beaux Arts, Renaissance, and Georgian—all of which are European in origin. “The Declaration of Independence I bring to you today is no mere negation,” Wright told a British audience in 1939, a few years after completing his masterpiece, Fallingwater. “It is affirmative denial of the validity of any such thing as … servility on this earth and it is assertion of the right of life to live.”

And yet for these very reasons, it’s also perfectly fitting that Wright’s name was left off the Trump administration’s list of architectural correctness. The idea of a government-proclaimed style of individualistic non-conformity is simply oxymoronic. That’s why Wright took it in stride when Arizona politicians rejected his Oasis proposal. “A man like myself would never be thought of in connection with a government job,” he told a congressional committee. And—with only one exception, and that one posthumous—he was right.

Organic Architecture’s democratic essence doesn’t serve an authoritarian agenda. And any form of mandated architecture would for that very reason cease to be “Organic,” anyway. The very notion calls to mind Groucho Marx’s famous quip about never joining a club that would accept him as a member. Wright, however, would have put it differently. When he met Franklin Roosevelt at the White House, he’s said to have remarked, “I’d rather be Wright than be president.”

Still, he would likely have viewed Trump’s architecture order as worse than merely silly. Any attempt to retreat into Neo-Classicism’s clichés in 2025 is surely a betrayal of something precious about the American character; an effort to impose “the grandeurs of the past” by fiat on the one nation least suited to such dictates. The consequence can only be a hollow, out-of-place architecture, one just as unlikely to inspire national pride as Internationalism or Brutalism ever were.

Consider the Tuscaloosa federal courthouse, built in 2011, which helped inspire the White House’s orders. It’s the exact opposite of Wright’s Oasis. A fine replica of a Greek temple, it features all the “grandeurs of the past”: gilded pilasters, stone porticoes, sweeping staircases. But if public buildings should “make the people love their native country,” it is almost a total failure. The one thing it does not look like is a 21st-century American courthSouse. Its sole redeeming qualities, and the ones the public appears to like most, are its interior murals depicting scenes from Alabama history—which have no classical Greek precedent. In other words, the building is at its best when it diverges from its memorized formula to offer an American touch.

Obedient recitation is not an American art. Nor, for that matter, is it Greek. As art historian Julia Friedman observed, the original handbook for federal architecture opened with a quotation from a speech in which President John F. Kennedy quoted Pericles’ funeral address: “We do not imitate—for we are a model to others.” Kennedy’s point, Friedman wrote, was to prioritize “not only maintaining the canon, but adding to it.” Or, as Wright put it, “an American is in duty bound to establish new traditions in harmony with his new ideals of Freedom and Individuality.”

Wright actually predicted that officials might try something like the Trump executive order. In his 1945 book When Democracy Builds, he described such orders as “a form of universal conscription.” Under the delusion that culture can be imposed by “some preconceived, imposed, external idea of Form,” politicians always seem to be “offer[ing] for the fifth time, as progress, only the same old [Neo-Classicism], its face merely lifted, to mark our ‘progress’ … [and] call[ing] world-wide attention to our ‘greatness.’” Americans should reject such authoritarian decrees, he wrote, and build instead “an architecture that seeks to serve man rather than to become … one of those forces that try to rule over him.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.