The queen of Tex-Mex and the murderer: Selena’s legend lives on 30 years after her death

The denial of parole for Yolanda Saldívar, the woman who killed the Latin music star, revives the circumstances of the crime and the immeasurable legacy of a life cut short at age 23

The Selena Quintanilla-Pérez museum in Corpus Christi, a majority-Hispanic city in southern Texas facing the Gulf of Mexico, contains almost the entire universe of the Queen of Tex-Mex Music: hundreds of portraits of the singer, her red Porsche, her collection of Fabergé eggs, her awards and gold and platinum records, around 20 of the outfits she designed herself, and the stream of fans who pass by in groups every few minutes. There is no trace of the woman who shot her in the back, Yolanda Saldívar. And a subtle ellipsis —in the letters of condolence from, among others, then-president Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, then governor of Texas — acknowledges the death on March 31, 1995, of a 23-year-old artist who had already made history in the Latin pop industry and in the Mexican-American community in the United States.

“There’s no need to remember what happened; everyone knows, and it still hurts for many of us,” said two friends, “fans of the singer,” who came here from far away, Montana and Michigan, as they stood in the museum parking lot on March 20.

This Monday marks 30 years since that ”what happened,” and as much as Selena’s family and some of her fans may prefer to forget it, the tide of history insists on bringing those memories back. The anniversary isn’t particularly momentous, but it coincides with the first time that Saldívar, a petite 64-year-old woman who served as president of Selena’s fan club and managed the singer’s fashion business, was eligible for parole. The Texas Board of Pardons denied her request last Thursday, finding that “the attacker represents a continuing threat to public safety.” The board ruled that she must remain behind bars until at least 2030, when she can again request a review of the case.

A Houston judge sentenced her to life in prison in 1995 after a three-week “trial of the century” that marked —along with the O.J. Simpson trial held shortly before — the beginning of a golden age of justice as a show in the United States. The jury took just a little over two hours to find her guilty of first-degree murder for shooting Selena in a Corpus Christi motel room.

A spokesperson told EL PAÍS last week that “neither the family nor the heirs” were planning “to give interviews or make comments” at this time. They also did not grant permission to reproduce part of a casual conversation with the family patriarch, Abraham Quintanilla, while he was signing a copy of his memoir, A Father’s Dream: My Family’s Journey in Music. Quintanilla, 86, is the man who launched his daughter’s career, and he has maintained a tight control over her legacy from this squat building, which the family converted into a museum when they saw thousands of people making pilgrimages to the company’s offices, Q Productions, to mourn the diva’s death. The place has a well-stocked and bustling gift shop and a studio where they have continued to record Tejano and pop artists.

After learning of Saldívar’s ruling on Thursday, Suzette, Selena’s sister and drummer for Los Dinos, the band that accompanied the star, posted a message on Instagram, signed by the family and by Chris Pérez, widower of the singer and guitarist of Los Dinos, which said: “This decision reaffirms that justice continues to defend the beautiful life that was taken from us and millions of fans around the world far too soon.”

Everything indicates that the parole board still doesn’t believe Saldívar’s version of events, which she has maintained for 30 years, that it was all an “accident.” Nor does it believe the version of a person close to her who, in a recent article in The New York Post, anonymously said that the victim’s “aggressiveness” had caused the killer to pull the trigger.

“The accident theory, which is what she clung to throughout the trial, never held up,” explains Mark Skurka in a telephone conversation. He served as prosecutor on the case when he was a young lawyer in Corpus Christi, a working-class city that Selena never left, even at the height of her fame. “We had a confession, which was admitted into evidence, in which she never once uttered the word ‘accident.’ We convinced the jury that [Saldívar] was angry with Selena and terrified that she would leave her, as well as the idea of having to return to the meaningless life she had before meeting her. As for the argument of self-defense: what can you say? It’s very hard to believe you’re defending yourself against someone who’s been shot in the back. Besides, the victim wasn’t armed, and when you accidentally shoot someone, you do something to help them, especially considering that Saldívar was a registered nurse.”

That wasn’t the case. After being shot, Selena crawled to the front desk, where she collapsed. The motel staff called emergency services, but doctors were unable to save her.

That “cool and cloudy” Friday, Carlos Valdez, then the Nueces County District Attorney, was returning from lunch with friends when a sheriff’s deputy told him what had happened and that the suspect was in the Days Inn parking lot, locked in her truck, threatening suicide, while repeating between sobs that she didn’t want to “kill anyone.” “Saldívar kept the police and the negotiator on tenterhooks for 10 hours,” Valdez recalls in an interview with EL PAÍS. Once she was arrested, the case, “a simple murder,” says the now semi-retired jurist, fell on his desk. And his life changed forever.

Safe behind bars

“I think it’s better for her that they didn’t release her; at least she’s safe in there. Her life would be in danger on the streets,” warns Valdez, who believes that Saldívar’s entourage may have resorted to the “aggressiveness” argument when they saw that “the Menéndez brothers [sentenced to life imprisonment for killing their parents in 1989] might work as a reason to review their case. Yolanda has changed her story so many times in the last 30 years that she doesn’t know what to invent anymore.”

In his memoirs, published in 2021, Selena’s father writes that he is “100%” convinced that if the police hadn’t immediately arrived at the scene of the crime, Saldívar would have gone looking for him to kill him too. He describes his surprise at seeing “about 150 people” at the hospital’s emergency room when he arrived with his son, A. B., Selena’s record producer. He also says that, although he doesn’t remember it, he knows — because he saw it on a video online — that he appeared before the press to say, “A disgruntled employee killed my daughter this morning.”

Saldívar began working for Selena as the president of her fan club and eventually became a close friend of the singer, managing the fashion stores she opened in Corpus Christi and San Antonio to pursue her passion as a designer. In the weeks before the murder, Saldívar traveled to Monterrey to arrange the opening of a third store in the northern Mexican city, where Selena was also a star.

When Abraham Quintanilla received complaints from fan club members claiming they had paid for merchandise (signed photos, t-shirts, etc.) that never arrived, he held Saldívar accountable, including for the misappropriation of funds they had noticed in the company’s accounts. She defended itself by claiming the accusations were false. There was a meeting in which the singer’s father and sister, who was Saldívar’s original friend, threatened to fire her and take her to court for embezzlement. “That was the big mistake, not getting rid of her immediately,” says the journalist Joe Nick Patoski, who covered the trial and shortly afterward published the unauthorized biography Selena: Como la Flor, despite, he says, Abraham Quintanilla’s “threats.”

After that meeting, Saldívar bought a .38-caliber pistol at a San Antonio gun shop, saying she wanted it because she was a nurse and feared that the family of one of her terminally ill patients would attack her. In her statement, Saldívar said she bought the gun, later returning it to the store and then buying it again, because she was afraid of Selena’s father. Patoski does believe her on this point, given Quintanilla’s “ability to be intimidating in business dealings.” “Selena continued to trust her friend, I would say until the morning of her death, when she took Yolanda to the hospital after the latter told her the lie that she had been raped. That’s when she got fed up with her lies,” Patoski concludes.

The comings and goings of the weeks leading up to the murder are the focus of a controversial documentary released last year titled Selena and Yolanda, the Secrets Between Them, which focuses on two aspects of the investigation: a resignation letter from Saldívar, which the film’s producers believe casts doubt on the family and prosecutors’ account that the killer acted out of spite when she saw she was about to be fired, and the possible influence of threats “from the Mexican mafia” that prosecutors and defense attorneys received during the trial.

It also resurrected, with the insidious trappings of a contemporary true crime, the relationship between Selena and Ricardo Martínez, a plastic surgeon from Monterrey who was helping her with her business dealings in the city. “I don’t know if they had a romantic relationship, but I do know that Martínez, whose name didn’t appear in the trial until the end, was a mentor to her, and that he was helping her enter Mexico, where Texans who don’t speak Spanish well are despised and called pochos,” Patoski clarifies. “We mustn’t forget that Selena and her siblings grew up in a completely American environment, and that she had to reprogram herself to learn Spanish and the Mexican culture of her roots.”

Both Skurka and Valdez participated in that documentary, and both agree that it sold as breaking news several issues that had already been taken into account in the investigation. “The director [Billie Mintz] came in with a preconceived version of events and only used what suited his story,” says Valdez, who explains that he preferred to exclude suspicions of embezzlement from the trial so as not to “muddy a case that was very straightforward.” “Otherwise, the jury would still be deliberating,” he jokes.

Mintz explained in a telephone conversation this Friday that his intention wasn’t to exonerate Saldívar, whom he interviewed four times in prison (“she killed Selena, no one disputes that”), but to uncover the “truth.” “And the truth is, it wasn’t an intentional death, but a homicide.” He also believes Saldívar “wasn’t aware that the bullet hit” the victim. “The district attorney did his job very well: he needed to get a conviction. It was the press that failed, and the investigators. A lot of information was withheld, and Saldívar’s attorney [Douglas Tinker], who feared for his life, didn’t do enough. Someone being found guilty only means that the prosecutor managed to convince the jury of his version of events.”

The documentary was met with a mixture of disgust and morbid curiosity by Selena’s fans. Mintz, who was surprised to see on social media how many of those fans (“more than a thousand”) had promised to kill Saldívar if she was released, says with some pride that it’s the “most-watched documentary in the history of Peacock [the platform that aired it] and also the lowest-rated.”

Conspiracy theories

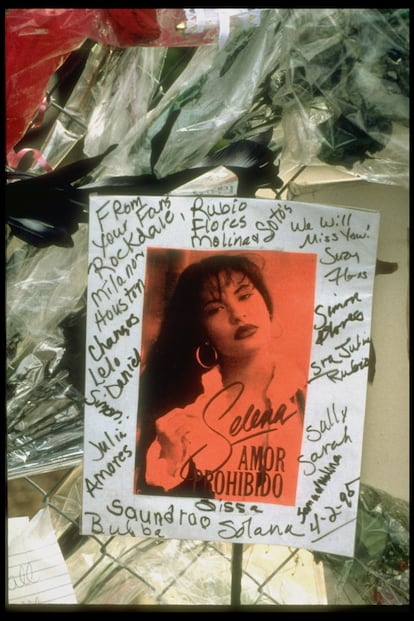

Valdez places the eagerness to review the case within the context of the “conspiracy theories” that surfaced from the beginning. As early as the hospital, in fact: for years, a hoax circulated that Selena had been pregnant at the time of death (not true), and that she died because her father, a Jehovah’s Witness, refused a blood transfusion (she got one; it was useless). At the funeral, held three days after the killing, some 65,000 people attended a Corpus Christi auditorium that was renamed after the singer a year later. A woman began shouting that Selena hadn’t really died, that it was all a “hoax.” The family allowed the coffin to be opened, but not photos. Of course, that didn’t stop someone from taking them anyway.

“At trial, the defense focused on trying to prove that the father was terrorizing Saldívar and wanted to end her relationship with Selena as part of his plan to control his children,” Valdez recalls. “When I questioned Abraham, I asked him all the questions I needed to dismantle Tinker’s arguments under oath, and I succeeded, because Tinker declined to call him to testify afterward.” Quintanilla applauds the prosecutor’s strategy in his memoirs, which largely read like a justification for his decisions and a self-defense against those who portray him as a despot toward his children and a man who lived through them the success that he never achieved himself when he had his own doo-wop band in the 1960s, also called Los Dinos.

Many fans have accused him of over-sanitizing Selena’s image, especially with the 2020 Netflix series dedicated to her. “Abraham is only interested in fairy tales. That was the story of how he and his firstborn managed to extract musical greatness from a Barbie doll named Selena, who had nothing to say,” believes Patoski, the journalist, who is convinced that the artist was ready to leave the nest at the time of her death: “She was planning to move away from her parents, pursue her great passion, fashion, do a crossover with an English-language album she was working on, and change her manager and producer.”

Patoski also recalls that in 2012, Pérez, the widower, wrote a book titled To Selena with Love, which he later wanted to turn into a series. Two months after the death of Selena, who died without a will, the young man signed a contract giving his father-in-law “exclusive authority to exploit Selena’s name, voice, signature, photograph, and likeness” in perpetuity. So in 2016, the father sued the guitarist to stop him from moving forward with his plans. In 2021, the dispute between the two was resolved “amicably,” and the widower’s relationship with his in-laws was restored a couple of years later. [Pérez did not respond to this newspaper’s request for an interview.]

Had it been filmed, the series would have joined an extensive list of audiovisual products inaugurated by the successful biopic in which Jennifer Lopez played the singer in 1997. For now, the list is closed by the documentary Selena y los Dinos, released this year, based on home recordings and telling the story of the musical evolution of the band of a nine-year-old girl born in Lake Front (Texas) who ended up becoming the Queen of Tejano Music by tirelessly performing at small-time stages until she broke into the big leagues.

“Selena broke many barriers,” explains Guadalupe San Miguel, a professor at the University of Houston and author of the essay Tejano Proud: Tex-Mex Music in the 20th Century (2002). “She comes from the 1960s renewal of Tejano music [a style popular in South Texas and parts of Northern Mexico] known as the onda grupera. Selena snatched the crown from Laura Canales: like her, she triumphed in a man’s world. Unlike Canales, she enjoyed the exposure of a major label, EMI, and was the first Mexican-American artist to win a Grammy. She changed the genre completely, popularizing cumbia as a valid language.” Her death, the expert indicates, inaugurated the decline of Tex-Mex music at the beginning of the century.

The same cannot be said of Selena: her legacy has never stopped growing, inspiring a copious crop of books and academic essays that examine her in light of everything from queer theory to her influence as a role model for the Hispanic community. Her first posthumous album, Dreaming of You, recorded in English and released in the summer of 1995, sold 175,000 copies in a single day and inaugurated a phenomenon that professor and poet Deborah Paredez christened Selenidad in an essay of the same name in which she compares her to two other legendary women: Frida Kahlo and Evita Perón. She uses the term Selenidad to define the fertile cultural legacy of “a Latina born in the United States” who displayed a “proud working-class aesthetic, inextricably linked to her complexion: she was dark-skinned, undeniably voluptuous, and sported black hair that she never wanted to bleach.”

Paredez also highlights the “speed” of a canonization spurred by her good-girl image. It doesn’t let up, despite the generational changes. “Sometimes it seems that she’s being listened to even more now than before she died,” notes Anamaria Sayre, co-host of the NPR podcast Alt.Latino. “She’s a legend, and the circumstances of her death, which triggered a collective outpouring of grief, have only made it even greater. She was a very important symbol for the Mexican-American community [to which Sayre, who wasn’t born yet when Selena died, belongs] and a source of pride and unification. In our homes, she’s almost a religious figure.”

In Corpus Christi, entire families make pilgrimages to key points along the Selena route through the city to prove that this spell transcends the ages. There’s the museum, the fenced grave that always has fresh flowers, the murals in her honor, the popular restaurant Hi-Ho, which the artist never stopped frequenting, and the lookout point Mirador de La Flor, where María Lárraga, with her husband and four children, stood last week at the foot of the bronze statue commemorating Selena, who is depicted wearing one of her signature outfits (pants, bra and jacket). Lárraga said she remembered “as if it were yesterday” going with some friends to the singer’s final concert, which broke attendance records in Houston in February 1995.

Like the other residents of South Texas, Lárraga, then a teenager, can’t forget March 31, 1995, when she dropped what she was doing to glue herself to the television set. That day, the networks interrupted their regular programming to cut to the crime scene, where Saldívar was threatening to commit suicide in her van.

The motel is still standing, albeit with a different name. Management also changed the number of the room overlooking the kidney-shaped pool where it all happened, to avoid the temptation of necrotourism. After being shot in the back, Selena circled the building to the front desk, where, according to witnesses, she said, “Close the door, or she’ll shoot me again!” before uttering her final words: “Yolanda... [room] 158.” Thirty years later, the macabre echo of those words still resonates in Corpus Christi.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.