By continuing to browse our site you agree to our use of cookies, revised Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. You can change your cookie settings through your browser.

I agree

Search Trends

CHOOSE YOUR LANGUAGE

- Albanian Shqip

- Arabic العربية

- Belarusian Беларуская

- Bengali বাংলা

- Bulgarian Български

- Cambodian ខ្មែរ

- Croatian Hrvatski

- Czech Český

- English English

- Esperanto Esperanto

- Filipino Filipino

- French Français

- German Deutsch

- Greek Ελληνικά

- Hausa Hausa

- Hebrew עברית

- Hungarian Magyar

- Hindi हिन्दी

- Indonesian Bahasa Indonesia

- Italian Italiano

- Japanese 日本語

- Korean 한국어

- Lao ລາວ

- Malay Bahasa Melayu

- Mongolian Монгол

- Myanmar မြန်မာဘာသာ

- Nepali नेपाली

- Persian فارسی

- Polish Polski

- Portuguese Português

- Pashto پښتو

- Romanian Română

- Russian Русский

- Serbian Српски

- Sinhalese සිංහල

- Spanish Español

- Swahili Kiswahili

- Tamil தமிழ்

- Thai ไทย

- Turkish Türkçe

- Ukrainian Українська

- Urdu اردو

- Vietnamese Tiếng Việt

Copyright © 2024 CGTN.

京ICP备20000184号

CHOOSE YOUR LANGUAGE

- Albanian Shqip

- Arabic العربية

- Belarusian Беларуская

- Bengali বাংলা

- Bulgarian Български

- Cambodian ខ្មែរ

- Croatian Hrvatski

- Czech Český

- English English

- Esperanto Esperanto

- Filipino Filipino

- French Français

- German Deutsch

- Greek Ελληνικά

- Hausa Hausa

- Hebrew עברית

- Hungarian Magyar

- Hindi हिन्दी

- Indonesian Bahasa Indonesia

- Italian Italiano

- Japanese 日本語

- Korean 한국어

- Lao ລາວ

- Malay Bahasa Melayu

- Mongolian Монгол

- Myanmar မြန်မာဘာသာ

- Nepali नेपाली

- Persian فارسی

- Polish Polski

- Portuguese Português

- Pashto پښتو

- Romanian Română

- Russian Русский

- Serbian Српски

- Sinhalese සිංහල

- Spanish Español

- Swahili Kiswahili

- Tamil தமிழ்

- Thai ไทย

- Turkish Türkçe

- Ukrainian Українська

- Urdu اردو

- Vietnamese Tiếng Việt

Copyright © 2024 CGTN.

京ICP备20000184号

互联网新闻信息许可证10120180008

Disinformation report hotline: 010-85061466

Editor's note: Warwick Powell is a senior fellow at Taihe Institute and Advisor to Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

In 1893, Clark Stanley arrived at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, also known as the Chicago World's Fair. There, on stage, he proceeded to pull out a rattlesnake from a sack. Raising the snake aloft, he slit it open with a knife and placed it in a vat of boiling water. The snake's fat rose to the surface. Boasting of its healing powers, he skimmed the fat off the water's surface, bottled it and sold it to the crowd. Stanley sold this fat as Clark Stanley's Snake Oil Liniment. He went on to open two manufacturing facilities in Beverly, Massachusetts, and Providence, Rhode Island.

On May 20, 1916, the US Attorney for the District of Rhode Island filed against Stanley, alleging that a shipment of Stanley's Snake Oil Liniment was in violation of the Food and Drug Act. Analysis of a sample of the liniment by the Bureau of Chemistry of the Department of Agriculture found that it primarily contained mineral oil, a fatty oil believed to be beef fat, red pepper and turpentine. Stanley was fined $20 for violating the Act (about $500 in today's terms), by "falsely and fraudulently representing it as a remedy for all pain."

Snake oil became an epithet for fraud - a promise of a solution to all and sundry ailments, when it was no such thing. Stanley's commercial empire grew and then died with the passing of America's gilded age.

US President Donald Trump walks to board Marine One as he departs the White House in Washington, DC, March 28, 2025. /VCG

The gilded age of the 1870s through to the late 1890s holds a particularly special place in contemporary American political culture. America is on the verge of a new golden age, so promises President Donald Trump. He harks back to the period of America's gilded age - and wistfully eulogizes William McKinley as his favorite President. McKinley, President between 1897 and 1901 (when he was assassinated after being re-elected), at the tail-end of the gilded age, was known for his protectionist proclivities, in which economic policy was anchored by a commitment to an expansive regime of trade tariffs. McKinley referred to himself as "a tariff man, standing on a tariff platform." Trump dubs McKinley the "tariff king".

According to Trump, "President McKinley made our country very rich through tariffs and through talent." For him, McKinley "was a strong believer in tariffs; and we were actually probably the wealthiest of any time, relatively speaking, than at any time in the history of our country." Trump clearly links a belief in American relative wealth at the time with McKinley's tariffs.

For Trump, tariffs are meant to arrest and ultimately turn around American economic decline. For Trump, economic strength and national prowess is grounded in dominance in manufacturing. Tariffs are meant to reduce America's trade deficit, staunch the loss of manufacturing employment (and perhaps turn it around) and catalyze investment in manufacturing capacity … to 'make America great again'. If these are the ostensible objectives of reliance on tariffs, the question is whether tariffs have worked their magic so far.

US President Donald Trump signs an Executive Order imposing a 25 percent tariff on imports of automobiles and certain automobile parts, in the Oval Office of the White House, March 26, 2025. /VCG

The Evidence so far

There is mounting evidence from Trump's first term and its legacy about the efficacy of tariffs insofar as their stated aims are concerned. The evidence leans heavily towards demonstrating that tariffs were at best neutral in effect, or worse, counterproductive. Snake oil, anyone?

In a 2024 paper, David Autor and his co-authors explored the economic and political consequences of the 2018-2019 trade war between the United States, China and other US trade partners at the detailed geographic level. The salutary conclusion is that so far, "the trade-war has not provided economic help to the US heartland." The authors observe that, "import tariffs on foreign goods neither raised nor lowered US employment in newly-protected sectors; retaliatory tariffs had clear negative employment impacts, primarily in agriculture; and these harms were only partly mitigated by compensatory US agricultural subsidies." The net effect economically speaking was negative. This finding reinforces the growing body of empirical evidence that concludes that Trump Tariffs 1.0 have led to net negative results on American welfare.

In a 2019 paper for the Federal Reserve Board, Aaron Flaaen and Justin Pierce found that any small positive employment effect of direct import protection was undermined by larger negative effects from rising input costs and retaliatory tariffs. They concluded that "U.S. manufacturing industries more exposed to tariff increases experience relative reductions in employment as a positive effect from import protection is offset by larger negative effects from rising input costs and retaliatory tariffs. Higher tariffs are also associated with relative increases in producer prices via rising input costs." Flaaen and Pierce's work goes to the heart of the flow-on effects of tariffs, which may contribute to employment gains in the directly protected industries but ultimately lead to net job losses as higher costs filter through into downstream sectors. Javorcik and co-authors in a 2022 paper for the World Bank Group analyzed the impact of the 2018 tariffs on employment by way of analyzing job offers. They found that tariffs on imported inputs and retaliatory tariffs resulted in "a relative decline in online job postings in affected commuting zones." Conversely, they found no evidence of positive impacts of import protection on job openings, concluding that "the tariffs led to a combined effect of 175,000 fewer job postings in 2018, or 0.6 percent of the US total, with two-thirds of this aggregate decline due to the imported input tariffs and one third due to retaliatory tariffs."

The White House, Washington, DC, March 10, 2025. /VCG

Between 2018 and 2023, according to data from the St Louis Fed, the US manufacturing sector saw an increase of approximately 200,000 jobs, growing from about 12.7 million to 12.9 million employees. However, during the same period, total non-farm employment in the US increased from approximately 149 million in 2018 to 156 million in 2023, reflecting a growth of about 7 million jobs. This indicates that while manufacturing employment grew by roughly 1.6 percent, total employment expanded by about 4.7 percent over the five-year span, suggesting that manufacturing employment growth lagged behind overall employment growth. Tariffs imposed since 2018 did not prima facie lead to a resurgence in manufacturing employment.

American manufacturing has seen output growth expand between 2018 and 2023, however. According to Statista, manufacturing output, as measured by real value-added, increased from $2.2 trillion in 2018 to $2.8 trillion in 2023, marking a growth of approximately 27 percent. Over the same period, the US GDP grew from about $20.5 trillion in 2018 to $25.5 trillion in 2023, indicating an overall economic growth of approximately 24 percent, suggesting that manufacturing output growth marginally exceeded that of the economy as a whole. This disparity suggests productivity improvements within the manufacturing sector, as output increased more substantially than employment, again suggestive that if one of the main goals of tariffs is to rejuvenate manufacturing employment, then the results so far are less than encouraging.

Lastly, we can consider American manufacturing's net trade position. Recall that one of the main concerns is the net trade deficit in manufacturing. Between 2018 and 2023, US exports of manufactured goods saw an overall increase. In 2021, manufacturers exported $1.4 trillion in goods, accounting for a significant portion of total US exports. By 2024, total US exports of goods and services reached $3.2 trillion, up from $3.1 trillion in 2023. Despite the increase in exports, however, the US continued to run a trade deficit in manufactured goods. In 2024, the overall goods and services deficit was $918.4 billion, an increase of $133.5 billion from 2023, according to data from the US Census Bureau and the US Bureau of Economic Analysis. This widening deficit suggests that imports of manufactured goods outpaced exports, leading to a negative net trade position for the sector. Again, despite the introduction of tariffs, the net deficit in manufactured trade continued to widen.

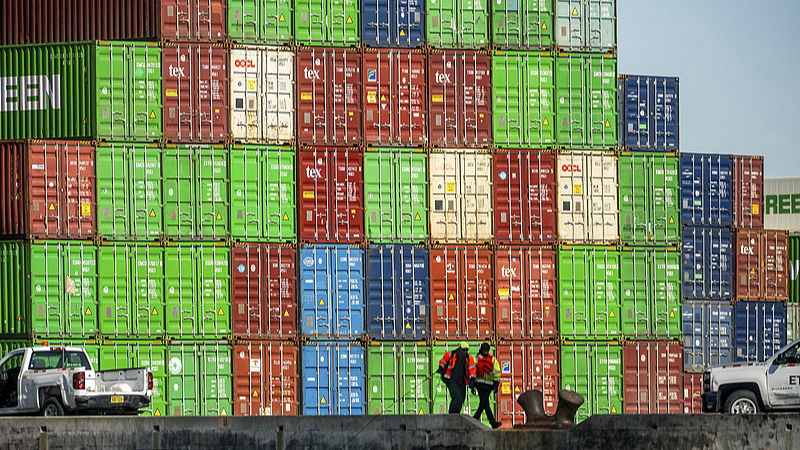

Shipping containers at the Port of Tacoma in Tacoma, Washington, US, on Thursday, March 27, 2025. /VCG

The Case of Steel

The case of the steel industry is instructive. A 25 percent tariff on steel products was first imposed in March 2018, under national security provisions in Section 23 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. Canada, Mexico and the European Union were exempted from the tariffs until the end of May 2018, when the US reached an agreement with Canada and Mexico to remove tariffs in May 2019. South Korea, Australia, Argentina, and Brazil were granted permanent exemptions to the tariffs until December 2019.

The tariffs have led to increased domestic steel prices, with about half of the tariffs passed through into domestic prices, according to a January 2020 study for the National Bureau of Economic Research. Increased domestic costs disadvantage US exporters, which according to a recent study by economists at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, the US Census Bureau and the University of Michigan, is associated with lower growth in export sales for American firms. Ironically, the increased cost of steel also disadvantages American firms when they compete with foreign rivals in the home market. This is evidenced by the fact that since the steel tariffs were put into place, hundreds of American firms have filed nearly 100,000 requests for exemptions from steel tariffs, as of early 2020.

As for employment effects, the impact on steel-producing industries has been limited. By November 2019, there were about 1,000 more jobs than in March 2018 (when the tariffs were imposed). However, the tariffs have likely prevented other steel-related jobs from emerging due to cost uncompetitiveness, or have actually resulted in downstream job losses due to softening global conditions and other cascading effects. These adverse implications have been identified by Lydia Cox in a recent paper, which shows that "upstream steel tariffs have highly persistent negative impacts on the competitiveness of US downstream industry exports". Lydia Cox and Kadee Russ have estimated that the creation of 1,000 jobs upstream came at the cost of 75,000 jobs downstream. Furthermore, ongoing technological development is likely to play an overriding role in displacing workers in steel production as shown by research by Allan Collard-Wexler and Jan De Loecker (2015). Tariffs simply don't deal with these realities.

Workers at the United States Steel Corporations Edgar Thomson Plant end their shift at the plant in Braddock, Pennsylvania, March 4, 2025. /VCG

An Alternative Diagnosis

The hollowing out of American manufacturing employment has been a clear trend since the 1960s, reaching a nadir in the early 2010s. The total employment level has remained relatively unchanged ever since. Similarly, output as a proportion of GDP also experienced a secular decline until the early 2010s, before leveling off. Declining employment and relative contribution to GDP reflect significant structural changes in the American political economy, which have less to do with trade policy and more to do with the growing dominance of the finance sector, increased concentration and the reduction in the relative complexity of the US economy, as documented by Atlas of Economic Complexity project at Harvard University.

Researchers such as Imad Moosa, Maria Ivanova, Braun and Milberg and Wilker amongst many others have shown how growth in financialization since the 1970s adversely impacts capital accumulation in American industry. Using the IMF's index of "financial development," Moosa demonstrates the inverse relationship between the expansion of financialization and the contraction of employment in American manufacturing. Trade impacts were, arguably, after effects. Yet, we see trade policy take center stage in American foreign economic policy, which simply does not address the chronic structural imbalances of the financialized American economy. Trade policy, anchored by protective measures, finds traction not because of economic efficacy but because of its emotive effects. This political dividend is mobilized through the politics of nostalgia.

Trump's tariffs are unlikely to return America to a bygone era of greatness. The gilded age may have delivered tariffs, but it also gave us the likes of Clark Stanley and his Snake Oil Liniment. Tariffs since 2018 have been a bit like snake oil, promising to cure-all but with questionable and at times counterproductive effects.