In 2022, University of Nebraska Medical Center researchers published a study showing a correlation between rural areas with high levels of nitrate in water and high rates of childhood cancer.

That study drew suspicion from an interesting source: the state’s top drinking water administrator, Sue Dempsey.

In an email to colleagues at the Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy, including its then-director Jim Macy, Dempsey cast doubt on the study and appeared to downplay the threat of nitrate in Nebraska’s drinking water.

“We are an agricultural state, so kids working on family farms are exposed to many pesticides and fertilizers in addition to, perhaps, high nitrates in their drinking water,” Dempsey wrote. “I believe it is a combination of multiple chemical exposures, poor US diets, and lack of exercise that makes children more susceptible.”

The email was among a tranche of records examined by the Flatwater Free Press following its years-long court fight to obtain public records related to the water Nebraskans drink.

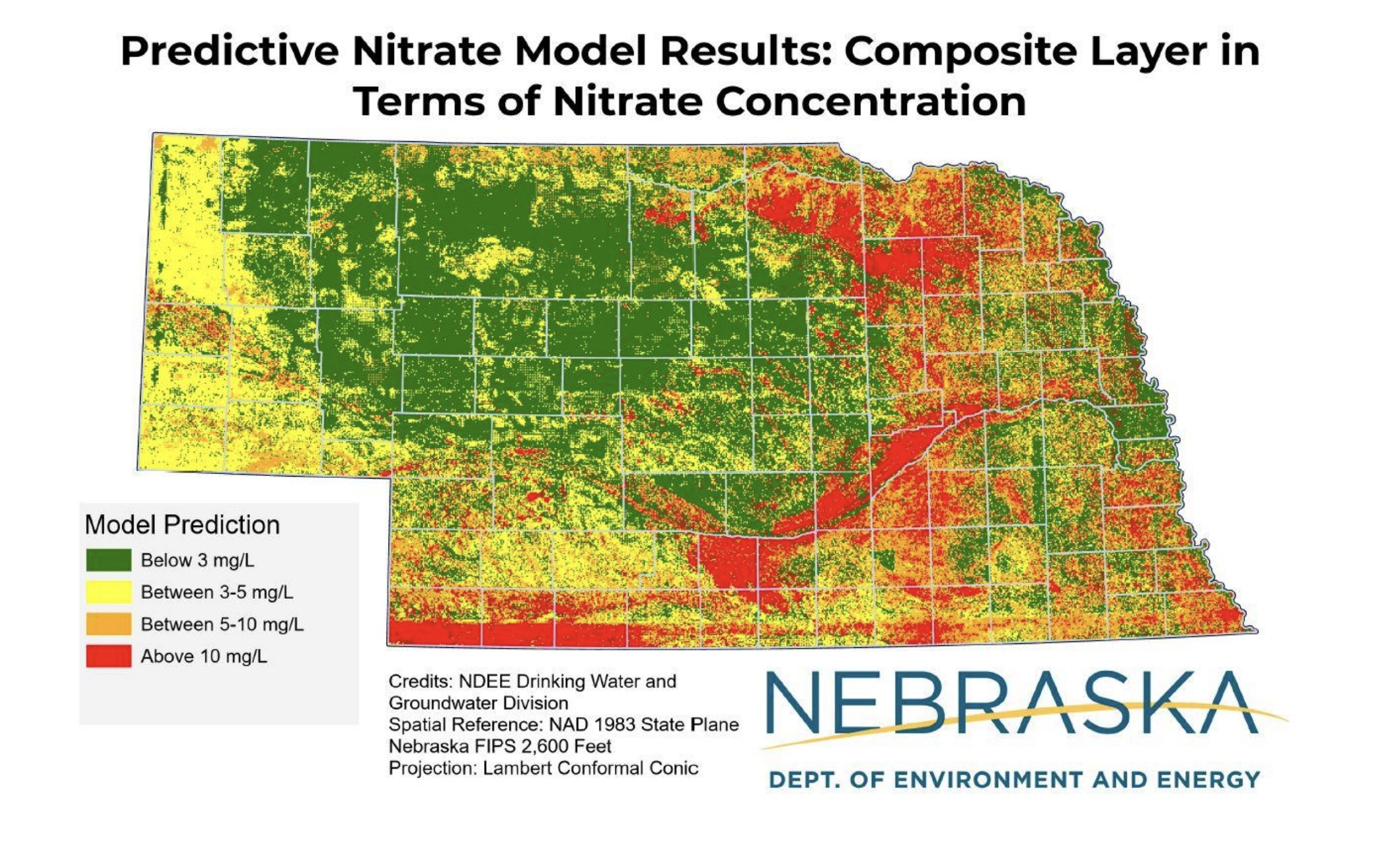

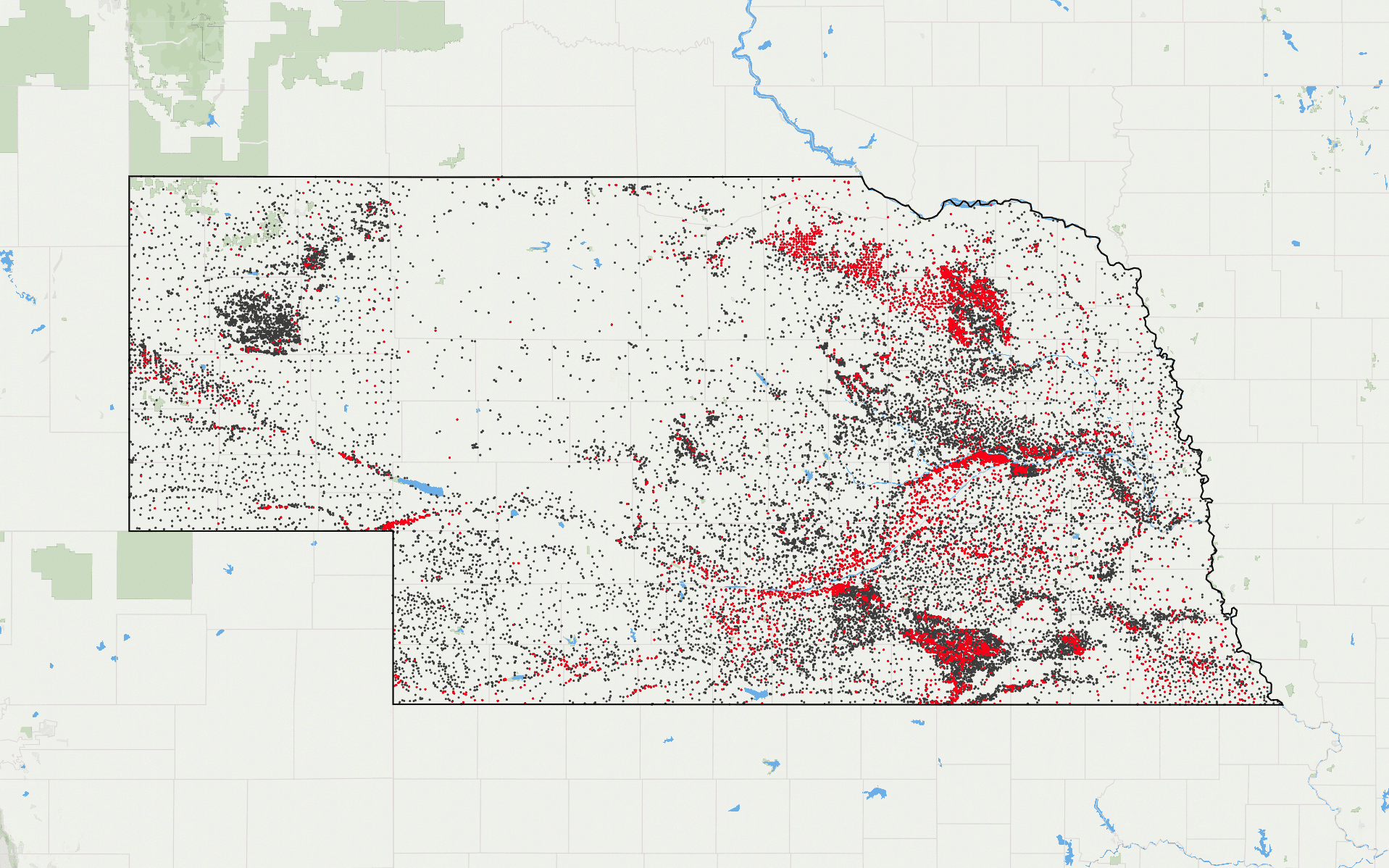

Dempsey’s message is one of several examples of state leaders’ approach to nitrate, which has continued to show up at high levels in the Ogallala Aquifer, public water systems and especially in rural Nebraskans’ drinking water. Nebraska has the highest pediatric cancer rate west of Pennsylvania, which experts suspect, and studies suggest, is tied to the water we’re drinking.

The emails show that NDEE employees have for years been aware of nitrate issues, and have long fielded pleas from Nebraskans worried about their drinking water.

But inside the agency, doubts existed and concrete action often appeared to lag, though University of Nebraska experts have now done multiple studies showing the dangers of excessive nitrogen in groundwater.

Dan Snow, a water testing expert and director of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Water Sciences Lab, pointed out in a 2023 email to Macy and other state leaders that increased well testing and treatment is needed, particularly as uranium and arsenic show up more and more in rural and small-town water supplies.

He highlighted different studies that show nitrate contamination can’t be dismissed as a thing that happened solely because of the agricultural practices of the past. He suggested that it will affect the state both now and into the future.

He wrote, “… this is just not a ‘legacy’ nitrate issue that will gradually resolve itself over time.”

The email comes from the first batch of public records released after FFP and the State of Nebraska engaged in a long court battle over them.

In 2022, the newsroom filed a public records request for emails containing certain keywords related to nitrate from about 80 NDEE employees. The agency attempted to charge FFP $44,000 for those emails.

Flatwater sued the state agency, arguing the fees were excessive. The case went to the Nebraska Supreme Court, which sided with the state after a lower court judge ruled in FFP’s favor.

But days later, the Nebraska Legislature voted 39-0 to change state public records law, barring state agencies from having rank-and-file employees redact their own emails and then charging Nebraskans for those redactions.

In December, the Flatwater Free Press received six years of emails containing the keywords “nitrate,” “nutrient,” “fertilizer,” and “nitrogen” sent to or from Macy, the former director.

The 3,000 emails don’t capture the full picture of the agency’s response to nitrate in water, revealing only policy discussions that made it to its top leader.

Those discussions came during a period where new studies – including UNMC’s – prompted new talk about lowering the federal standard for how much nitrate can enter drinking water.

The Environmental Protection Agency in 1991 set the standard at 10 parts per million, to prevent infants from developing an oft-fatal disease known as “Blue Baby Syndrome.” But recent research, both in Nebraska and elsewhere, suggests that ingesting nitrate at levels lower than may harm humans, particularly children.

Eleanor Rogan, a UNMC public health professor who led one study, told FFP she would feel more comfortable if Nebraska children were drinking water with nitrate levels lower than 3 parts per million.

The EPA first noted the need to investigate whether the standard should be further lowered in 2010, citing new data potentially linking nitrate to cancer. The federal agency detailed a plan to make further assessments in 2017, paused it, then restarted it in 2023.

The nitrate standard has become a D.C. “political football … punted back and forth,” said David Cwiertny, a University of Iowa environmental engineering professor. But states can lower their own standards below the EPA’s, he said.

In her email discussing the UNMC study with colleagues, Dempsey said she doesn’t agree with lowering the drinking water standard for nitrate. She left her post as the state’s top drinking water official in 2022.

Reached by a Flatwater reporter, Dempsey declined to comment for this story.

After Flatwater published the 2022 series, “Our Dirty Water,” then-Gov. Pete Ricketts’ office received an email from a constituent petitioning him to “increase funding, regulations and enforcement impacting nitrate levels.”

The department drafted a list of talking points for Ricketts’ office, emphasizing their efforts in regular inspections and reviews of livestock facilities’ water monitoring results.

The state has spent millions of dollars treating the fallout from high nitrate, reporting shows. It has shouldered some cost for new treatment plants in small towns where water exceeds federal nitrate standards. It has split the cost with rural Nebraskans who need to filter out the nitrate in their drinking water wells. It has provided incentives for farmers who adopt best practices, trying to reduce the nitrate leaching into groundwater.

But the state has never addressed the root problem, said Tim Gragert, a Republican former state senator from Creighton in a recent interview.

“I think those that have the responsibilities are, in some way, just hoping this with time just kind of goes away, and we find a way to, once again, address this by treating the symptoms instead of the cause,” he said.

Gragert, whose hometown became the first in Nebraska to install a multi-million dollar treatment plant for nitrate, has long criticized the state for taking a hands-off approach to regulating livestock operations. During the interview, he said that NDEE “bends over backwards” to industry.

“I never did get anything out of working with Jim Macy … That’s just talk. He never followed through with any kind of action,” Gragert said.

Macy retired last year, then was appointed the head of EPA’s Region 7, which includes Nebraska and neighboring states.

He could not be reached for comment.

The state agency under Macy’s leadership did issue some citations. Agency emails show the department investigated two cases of manure application near two livestock facilities. In an email to Macy, NDEE deputy director Kara Valentine suggested going after livestock operations a bit more aggressively.

“Let’s consider doing a few test enforcement cases in this area to highlight the concern,” she wrote in the email.

Zach Hock-Reid, a former environmental specialist with NDEE, recently told the Flatwater Free Press that while many in the agency believed in more protections for groundwater quality, higher authorities “put the agency on the back foot before the conversation even begins.”

Focusing on water quality preservation, Hock-Reid thought his hands were tied, as Gov. Ricketts’ office and some legislators signaled to agency staff to not be alarmist and maintain the status quo.

“They wanted us to stay open and working, but I don’t think they really want us to push too far. They wanted to keep the public safe, but not hold interests accountable,” he said in an interview.

Cay Ewoldt led NDEE’s agriculture section, responsible for permitting livestock confinements, until 2022. In an interview, Ewoldt said the agency always tried to be forward-thinking while regulating runoff and leaching from livestock facilities, which are often called concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs.

But the state agency was always caught in a tough spot, Ewoldt said.

“That’s always been the really tough thing. Like, ‘OK, do you tell this farmer he can’t farm? Do you tell this CAFO they can’t have livestock?’”

The emails released to the Flatwater Free Press also show rural Nebraskans occasionally mounting campaigns – generally unsuccessful – to clean up a feedlot or hog barn near their homes.

Loren Siebrandt, who lived near West Point, complained to the state about a hog farm near his house for years, the emails show. He sent the department photos of dead pigs not covered by dirt, and alleged that bacteria and nitrate got into his water supply and caused his health to deteriorate. Siebrandt eventually left his home.

His domestic well, located less than a football field away from the hog farm’s burial pit, recorded sharply increasing nitrate levels from 2.1 parts per million in 2017 to 8.7 parts per million in 2020.

State law requires only 100 feet between a domestic well and a livestock facility. Even though the swine operation was at a legal distance, Siebrandt said Dempsey told him the hog farm was too close to his well, according to agency emails.

NDEE employees told Siebrandt the hog farm was complying with existing regulations, and also that Siebrandt’s own well didn’t have a proper seal and was violating state well registration requirements.

Siebrandt then turned to Brian Bruckner, then the assistant manager of the Lower Elkhorn Natural Resources District. NRD employees observed elevated nitrate levels in the area, and Bruckner sent a letter to the NDEE in 2020, suggesting the agency could recommend different ways that the hog farm could dispose of its dead animals.

He then wrote back to Siebrandt, an email obtained by FFP during a previous records request.

“The health situations that you are experiencing are horrible, and I’ve tried hard to get the Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy to take a closer look at things but they don’t seem to be responding any more effectively to the NRD than they were for you,” Bruckner wrote.

Siebrandt pleaded with Macy for help at a 2023 groundwater forum hosted by the Flatwater Free Press.

“Record of our interaction and effort to help him is clear,” Macy later wrote to staff, emails show. “I committed to one more well test and told him after that we are done.”

The following month, Macy emailed Siebrandt, noting his agency wouldn’t test Siebrandt’s well until it complied with state regulations.

Macy’s emails recorded no further follow-ups on Siebrandt’s case.

His emails also show occasional behind-the-scenes interaction with giant livestock operations.

In 2022, when owners of Blackshirt Feeders tried to build a 100,000-head feedlot — the largest in state history — in Benkelman, emails show they wanted the state regulatory agency involved early. Steve Martin, the director of a Nebraska livestock interest group, while organizing support for the feedlot, asked Macy to issue a letter meant to potentially ease any local opposition.

“Basically, that you were aware of the project and were comfortable with regulating it (as you would be with any feedlot). It is more reassurance that someone is on watch,” Martin wrote.

Ewoldt drafted the letter for Macy two days later, emails show.

Ewoldt recalled the agency starting to issue letters like this with the advent of large livestock or meat processing plants like Lincoln Premium Poultry. The agency never took sides on those projects, he said.

Facing fierce local opposition, owners of Blackshirt Feeders moved the project from Benkelman to its neighbor Haigler in southwestern Dundy County.

Later, an employee of Blackshirt Feeders’ engineering firm, Settje Agri-services and Engineering, emailed Macy, with updates on the new site, which would add 50,000 more cattle and a methane digester to the original plan.

The Flatwater Free Press sought comment from Dean Settje, owner and founder of Settje Agri-services. Settje agreed to be interviewed, but later stopped responding to calls and voicemails. Recently, he was appointed to the newly formed Water Quality and Quantity Task Force by Gov. Jim Pillen.

The feedlot started operating last year.

Mary Exner Spalding, a retired UNL professor and research chemist, said state leaders have been concerned about nitrate in water for a half century.

Spalding pioneered the research on identifying sources of Nebraska’s groundwater nitrate in the 1970s.

After scientists discovered much of it originated from farming practices, university leaders were reluctant to publicly share that information, she said in an interview.

“It was the university that didn’t really want the source identified, because there was so much funding back then from the fertilizer companies,” she said.

The university has studied nitrate loss from fertilizers since the 1940s and sought to advance public understanding of nitrate through its Extension publications and events, said Crystal Powers, water extension educator at the University of Nebraska.

[Editor’s note: The story was updated to include Powers’ comment. ]

In a 1987 paper, Spalding found the state’s groundwater protection policies to be “fragmentary and generally reactive.”

Then, in a seminal 2014 paper, Spalding examined approximately 44,000 water samples and discovered that nitrate levels were rising in groundwater in large swaths of Nebraska, increasingly exceeding the EPA standard for drinking water.

In recent years, experts and regulators have increasingly acknowledged the need for reducing nitrate in drinking water.

At a legislative hearing earlier this year, Gov. Jim Pillen said the state needs to be more aggressive in addressing the decades-long nitrate contamination.

“This has to stop. It cannot continue,” he said.

Dempsey’s successor, Laura Johnson, noted in an email that reducing nitrate is a priority for the safe drinking water program.

But the emails show that Nebraska hasn’t always taken the same steps as neighboring states as they all attempt to fix the problem.

Thirty states have developed a formal Nutrient Reduction Strategy, a framework aimed at minimizing the impacts of nitrogen and phosphorus on surface waters, according to the EPA.

Not Nebraska.

Nebraska doesn’t have one because the strategy focuses on surface water, and Nebraska isn’t a major contributor to surface water contamination, said NDEE spokesperson Amanda Woita. The state uses other programs and focuses on groundwater quality, Woita said.

Minnesota, which also relies heavily on groundwater for drinking water, has introduced fertilizer management plans, including better monitoring and training for farmers, as part of its nutrient reduction strategy.

A statewide nutrient reduction strategy would be a step in the right direction, said Tom Hoegemeyer, retired agronomist from Hooper.

Nebraskans today undoubtedly inherited a nitrate legacy from earlier generations, Hoegemeyer said, but rainfall still flushes unused nitrate down into the groundwater.

“We’re desperately in need of something widespread,” he said.

Our Dirty Water

Nebraska’s nitrate level has doubled in the past four decades. Despite this, state and local governments have taken little action to regulate the farming practices that lead to nitrate seeping into our drinking water.

6 Comments

Thank you so much for this article. It would appear that the fox is guarding the hen house. I don’t think this information is known to a large enough swath of the NE population.

Thank you, Yanqi, for supporting the lives of Nebraskans. My daughter is a pediatric cancer survivor, and your reporting has brought some much information to light that the general public doesn’t know. Keep up the great work!

Please email our elected representatives in Washington, and copy us on their replies (Senators and Congress)

Excellent account of the current state of Nebraska’s water contamination problem and history of how it got this way, and the players involved at the state and local levels.

Thanks for your hard work.

Would love to know how it is possible for someone to build (with a septic system and well) on the Loup River in Garfield County & in addition to that, rin cows on it. It was my inderstanding that building so close to the river with septic tank & well was not allowed. Let alone running cows on it!

Great reporting and really informative. I grew up in NE. Glad I left after this years ago.